Jake Cassar is a Central Coast-based public figure, a self taught ‘bushcraft’ educator and activist whose public persona blends wilderness survival with spiritualised faux-environmentalism. Through his business, Jake Cassar Bushcraft, he conducts workshops on what are presented as traditional survival techniques and native plant medicine, often framed as vehicles for deeper connection to the Australian bush (Jake Cassar Bushcraft, n.d.). In parallel, Cassar is the founder of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), an activist organisation that campaigns against what it claims are threats to the environment, often focusing on land developments proposed by Aboriginal-controlled entities such as the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC). While CEA frames its actions as conservationist and culturally protective, critics have noted that its rhetoric draws heavily from appropriated Aboriginal spiritual symbolism and anti-institutional conspiracy narratives, constituting what scholars have termed settler conspirituality (Cooke, 2025; Watego, 2021).

Together, Cassar’s dual ventures exemplify the convergence of settler masculinity, spiritual populism, and cultural appropriation under the guise of environmental and cultural stewardship.

QAnon, a conspiratorial meta-narrative originating in the United States, merges far-right political paranoia with millenarian spirituality and populist distrust of institutions. It has proven globally adaptable, mutating to reflect local anxieties about governance, identity, and legitimacy (Forberg, 2021; Phillips, 2025).

In Australia, one of its most potent localised expressions can be found in settler conspirituality: the ideological fusion of New Age spiritualism, conspiracy thinking, and settler-colonial logic (Ward & Voas, 2011; Watego, 2021).

This article proposes settler conspirituality describes the hybridised formation exemplified by Jake Cassar and the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA): a fusion of spiritualised conspiracy rhetoric, settler identity performance, and the appropriation of Aboriginal cultural motifs to contest Indigenous sovereignty.

This phenomenon is not new. Settler Australians have long mobilised narratives of sacred custodianship, environmental care, and ancestral knowledge to undermine Aboriginal governance. However, the contemporary manifestation incorporates distinctly post-truth, digital, and charismatic elements. CEA’s campaigns against Aboriginal-led developments on the Central Coast are framed not just as environmental protests, but as sacred missions in defence of land and spirit.

Historical analogues such as the Hindmarsh Island Bridge controversy or pastoralist resistance to native title in Western Queensland (Rowse, 1998; McGrath, 1995) illustrate how settler resistance often adopts the moral language of conservation and spirituality to assert land entitlement.

What differentiates the CEA formation is the seamless incorporation of QAnon-style revelationism, social media spectacle, and mythopoetic storytelling. In this way, CEA does not merely oppose development. It constructs an alternative moral and spiritual order in which settlers reclaim custodianship through ritualised defiance, conspiracy-inflected cosmology, and charismatic performance.

This article examines the case of Jake Cassar and CEA as a prism through which to analyse settler conspirituality as both a cultural formation and a political strategy.

Drawing on interdisciplinary literature from Indigenous studies, critical whiteness theory, conspiracy studies, and affect theory, the article explores how spiritual populism can be mobilised to displace Aboriginal governance, reassert settler belonging, and sanctify land theft under the guise of ecological reverence.

It argues that groups such as CEA weaponise spirituality and emotional community to invert narratives of dispossession, reframing Aboriginal land councils as desecrators and themselves as enlightened defenders of Country.

By engaging critically with Cassar’s rhetoric, media practices, and public performance, this article contributes to emergent research on white shamanism (Assaf, 2011; Durocher, 1999), affective populism (Marwick & Partin, 2022), and the settler-colonial appropriation of sacred ecologies (Moreton-Robinson, 2015).

It asks how Aboriginal sovereignty can be effectively re-centred when settler mimicry adapts to each new cultural terrain, cloaked in the aesthetics of healing, protection, and transcendence. Understanding this ideological formation is vital for any meaningful response to identity fraud, cultural appropriation, and the spiritualisation of colonial resistance.

Section 2: From Bushcraft to Apocalypse – Jake Cassar and the Rise of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA)

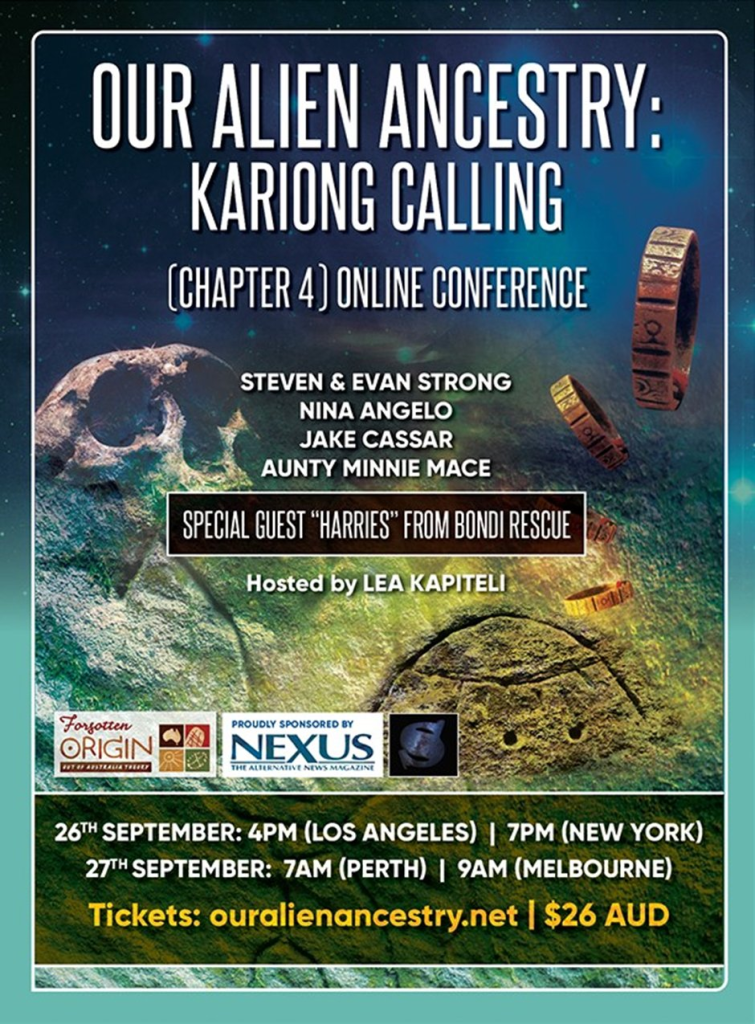

Since founding the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) in the 2010s, Cassar has repositioned himself as a populist defender of sacred land, blending environmentalist concern with esoteric and conspiratorial rhetoric. His public persona is built on a mixture of charisma, bush knowledge, mystical intuition, and anti-institutional critique; traits that resonate strongly with the emotional and narrative forms of QAnon-adjacent movements (Moskalenko & Imhoff, 2021; Baca, 2024).

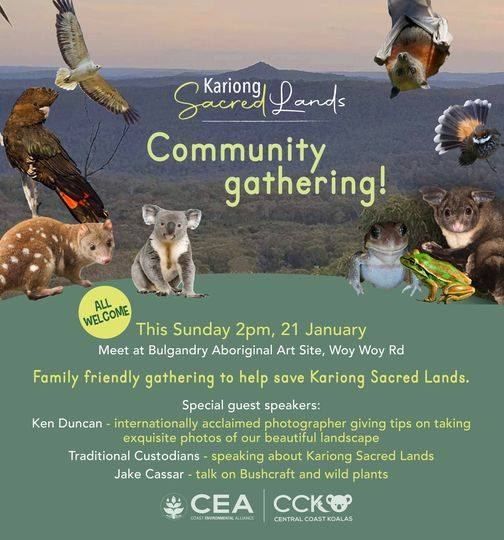

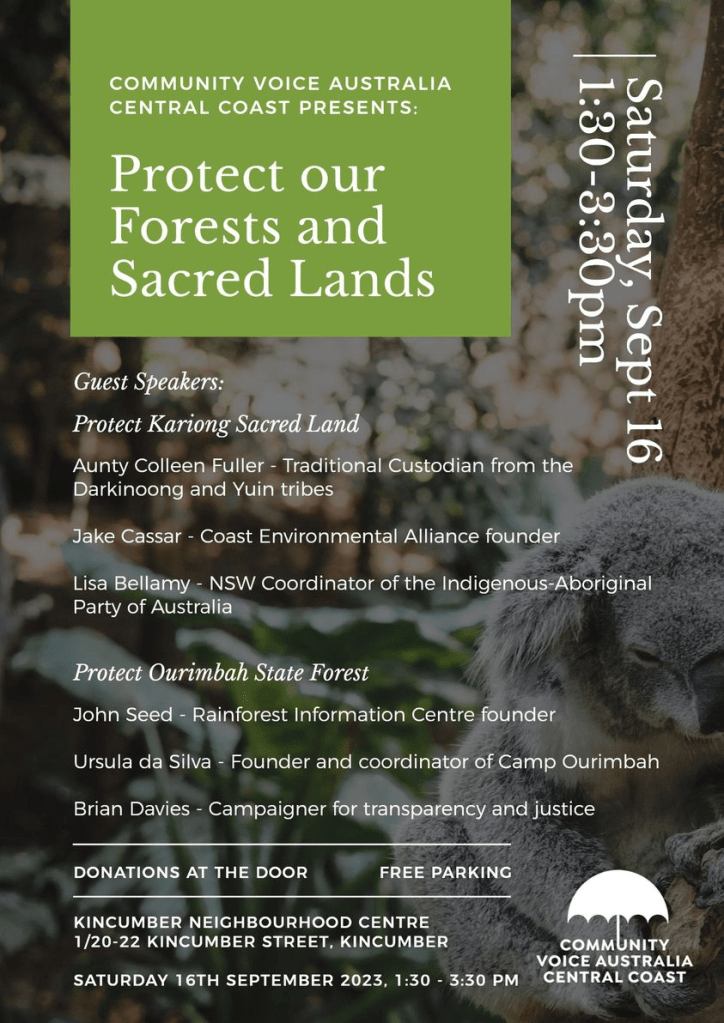

CEA began as a conservation-oriented alliance but quickly developed into a platform for activism against Aboriginal-led land developments, particularly those proposed by the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. Cassar and CEA have led vocal campaigns against developments at Kariong, Kincumber, and the Northern Beaches, claiming the sites are ecologically fragile, culturally sacred, and spiritually significant.

Yet their activism is saturated with settler-conspiritual tropes: Cassar invokes ancestral spirits, earth energies, and “true custodianship,” often implying that non-Aboriginal people, himself included, possess superior spiritual knowledge and moral entitlement to land (Watego, 2021).

A close reading of Cassar’s speeches, Facebook posts, and media appearances reveals a persistent distrust of government, a rejection of scientific and planning expertise, and an embrace of mystical insight and ancient wisdom.

He describes DLALC’s proposals as “cultural crimes,” speaks of “defending sacred Dreaming sites,” and has likened development to the desecration of the Earth’s soul. His rhetoric blends ecological crisis with spiritual warfare, asserting that unseen forces and ancient knowledge are under attack by corrupt institutions (Taplin, 2023; Van Badham, 2021).

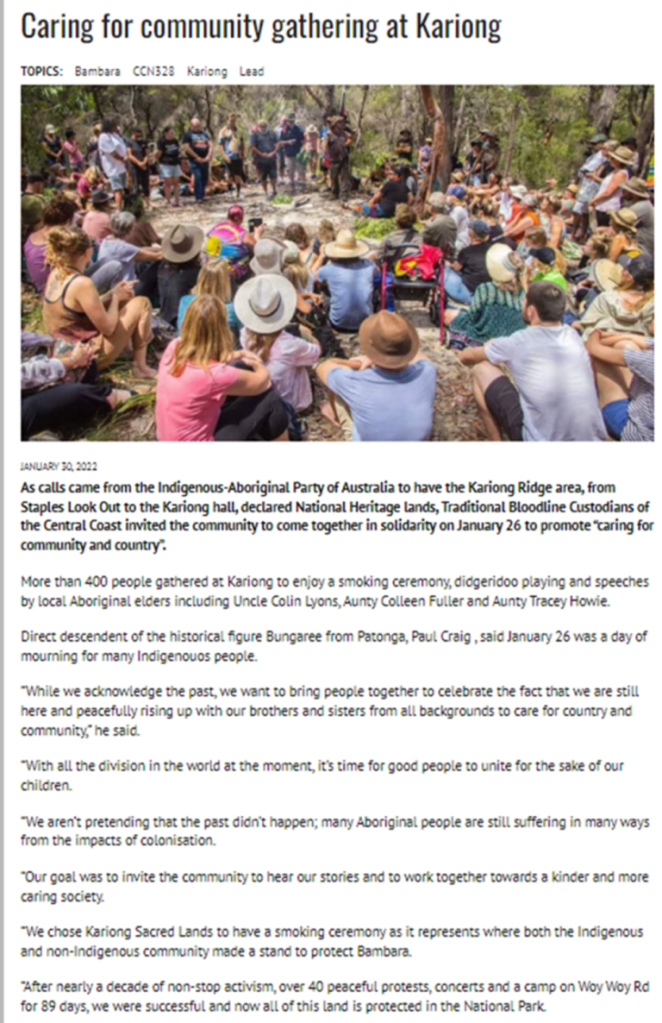

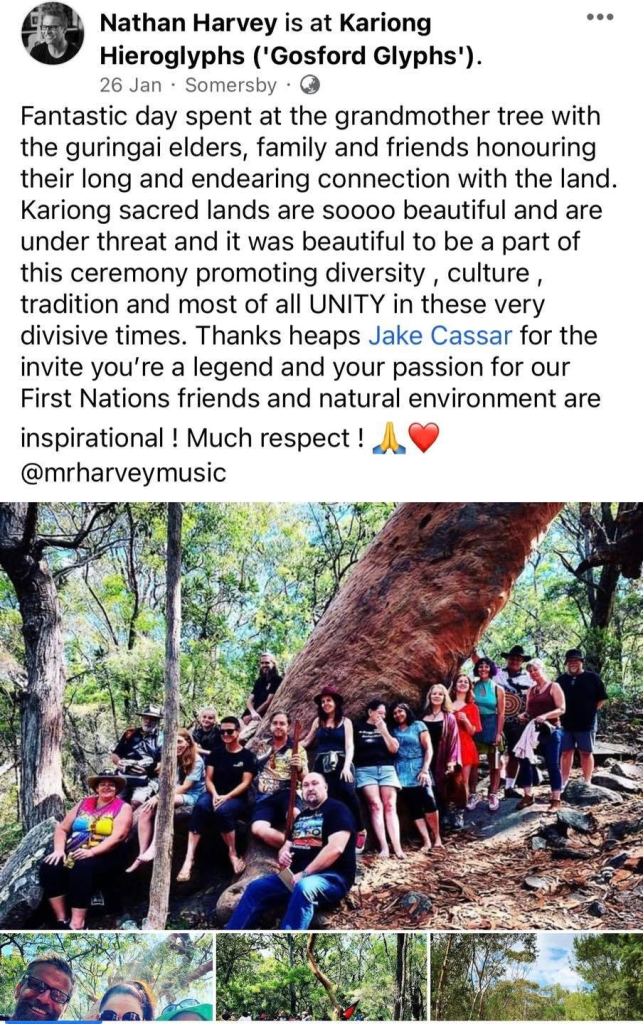

Cassar’s following is built through community events, “sacred site” tours, social media outreach, and performative rituals. These include yowie tracking, Dreamtime storytelling, and smoking ceremonies conducted by non-Indigenous participants.

CEA events are often infused with emotional intensity, gratitude rituals, and language of awakening, trauma, and healing; characteristics that align with cultic affect and conspiratorial spirituality (Zúquete, 2022; Crabtree et al., 2020).

Cassar’s rise illustrates the convergence of three forces: the affective charisma of alternative influencers, the emotional pull of eco-apocalyptic narrative, and the symbolic power of appropriated Aboriginal motifs. This combination forms the core of settler conspirituality, a politically charged mimicry that allows non-Indigenous actors to claim spiritual sovereignty while actively opposing Indigenous land justice.

Section 3: Apocalyptic Affect, QAnon Logic, and the Storm as Settler Revelation

The term “The Storm,” central to QAnon’s apocalyptic cosmology, functions as a floating signifier of catastrophe and redemption. It evokes spiritual warfare, systemic collapse, and the coming of moral reckoning.

While not explicitly publicly invoked by Jake Cassar, its thematic resonance permeates the rhetoric of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA). Cassar frequently speaks of hidden forces, sacred truths under siege, and the need for spiritual warriors to rise up against corruption, classic apocalyptic motifs drawn from conspiratorial and millenarian traditions (Toscano & Kinkle, 2015).

Cassar’s messaging draws heavily on QAnon-adjacent tropes: elite betrayal, covert knowledge, and spiritual battle. His framing of DLALC developments as “cultural crimes” committed by spiritually illegitimate authorities echoes QAnon’s portrayal of mainstream institutions as morally compromised.

Through Facebook posts, video content, and live speeches, Cassar offers his followers a redemptive narrative: they are the chosen few, awakened to the truth of sacred land under threat, called to act before it is too late (Phillips, 2025).

This narrative generates what scholars term “apocalyptic affect”, an emotional register comprising dread, transcendence, grief, and resolve (Renner et al., 2023). Followers are not only fearful of ecological collapse, but spiritually energised by the opportunity to participate in a mythic battle. Cassar’s rhetoric converts anxiety into a moral mission, positioning CEA as both seer and saviour.

These dynamics mirror the logic of QAnon, in which secrecy is spiritualised and revelation is personal. Believers feel that they alone perceive the hidden connections that expose the enemy’s schemes.

For Cassar’s audience, the DLALC is not simply a land council, it is a symbol of a larger betrayal of ancestral law and natural truth. Settler resistance is thus sanctified as a moral obligation.

Importantly, the affective structure of CEA’s movement resists empirical challenge. As in QAnon, dissenters are cast as either naïve or complicit. Counter-evidence is dismissed as propaganda. The emotional architecture of the movement insulates it from critique while deepening participants’ sense of righteousness and urgency.

Through this emotional and epistemological mechanism, settler conspirituality reverses the meaning of sovereignty. Aboriginal-led development becomes desecration. Settler-led activism becomes sacred defence.

The storm, in this framework, is not only a metaphor for collapse. It is a revelation of settler redemption, a ritualised drama of rebirth through spiritual struggle.

Section 4: Settler Identity, Masculinity, and Mythmaking

Jake Cassar’s appeal is inseparable from the cultural coding of rugged, outdoorsy masculinity and settler nationalism. His image evokes a heroic archetype; bushman, warrior, spiritual guide, fused with frontier aesthetics and survivalist ethos.

This persona plays into long-standing tropes of white Australian identity rooted in land mastery, physical resilience, and masculine independence (Cochrane, Gillespie, & Ross, 2024).

In the world of settler conspirituality, masculinity is moralised. Cassar’s survivalism is more than an aesthetic; it is cast as a sacred vocation. His bushcraft skills are imbued with spiritual meaning, presented as forms of ancestral remembrance and protection of sacred land.

He becomes a hybrid figure, part sage, part warrior, defending the Earth against desecration. This fusion reflects what cultural theorists describe as “apocalyptic manhood,” in which existential threat justifies hyper-masculine heroism (Renner et al., 2023).

These performances are deeply political. Cassar’s masculinity is tied to settler narratives of rightful belonging and protective authority. He asserts that he is defending not just nature, but a spiritual order embedded in the Australian bush.

This masculine settler spirituality mimics Aboriginal concepts like caring for Country, but displaces them by asserting white sovereignty in spiritual form. It enacts what Wolfe (2006) termed the logic of elimination, not simply by physical violence, but by symbolic supersession.

Cassar’s mythmaking also relies on the production of epic storylines: quests, sacred missions, betrayals, and awakenings. His social media content is saturated with mythic imagery; ancient portals, warrior protectors, cosmic wisdom, and hidden enemies.

These narratives cultivate a mythopoeic atmosphere in which followers are not merely activists, but spiritual warriors. The stakes are cosmic, and so are the rewards.

Ultimately, Cassar’s settler identity is not merely individual. It is performative, contagious, and collective. Through ritual, storytelling, and charismatic leadership, he enables his followers to inhabit a shared mythos. They are inducted into a narrative that affirms their belonging to land, history, and truth; while masking the dispossession of the First Peoples whose stories and symbols they appropriate.

Section 5: Emotional Communities and the Politics of Belonging

At the heart of CEA’s success lies its capacity to generate emotional communities; affective networks of belonging built through shared ritual, grievance, and spiritualised narrative. This echoes the broader dynamics of QAnon and other conspiratorial movements, where belief is not merely cognitive but relational, embodied, and affective (Zúquete, 2022; Renner et al., 2023).

Jake Cassar’s followers are not just environmental activists. They are inducted into a sacred narrative of awakening and protection, a community bonded by shared revelation and perceived persecution. Events such as forest walks, “sacred site” vigils, yowie expeditions, and communal ceremonies serve as affective intensifiers, building trust and solidarity while reinforcing oppositional identity.

Participants experience a sense of transformative purpose, emotional catharsis, and moral certainty; all hallmarks of high-demand social environments often described as cultic (Crabtree et al., 2020).

CEA’s emotional architecture is characterised by gratitude rituals, public displays of spiritual commitment, and regular affirmations of mission. In Facebook groups and community meetings, followers share testimonials of awakening, express outrage at DLALC developments, and reaffirm each other’s roles as guardians of sacred land. Emotional labour is central.

Followers are encouraged to cry, rage, heal, and commune, producing what Ahmed (2004, 2014) terms an “affective economy” where emotions circulate and bind the group together.

These emotional communities are not apolitical. They function as affective counterpublics; spaces where settler identity is reimagined through spiritual communion and political opposition. They invert the usual dynamics of marginalisation, presenting CEA members as an oppressed spiritual minority resisting hegemonic authority.

Cassar’s followers often frame themselves as victims of censorship, institutional betrayal, and cultural erasure. This persecutory inversion mirrors the populist logics of QAnon, where power is seen as illegitimate unless it aligns with personal revelation and communal truth (Phillips, 2025).

Within CEA, ritual practice plays a central role in this emotional formation. Followers engage in what might be termed ritual bricolage (Zablocki, 2001), piecing together elements of Aboriginal ceremony, such as smoking, dance, and storytelling, with settler mythologies and New Age practices.

These ceremonies are not only symbolic acts of solidarity but also tools of cultural mimicry and identity substitution. Specific performances, like yowie tracking expeditions and sacred vigils, often include gestures, chants, or narratives appropriated from Aboriginal cosmology but stripped of cultural context or authority.

This dynamic aligns with Sara Ahmed’s (2014) concept of the “stickiness” of emotions; how affect adheres to particular figures or symbols to construct communal identity. Cassar himself becomes one such figure of stickiness, embodying grief, rage, love, and truth.

Through his emotional cues, anguish at destruction, joy at communion, solemnity in ritual, he teaches followers how to feel and to whom those feelings should be directed.

Gender dynamics also play a role. CEA valorises masculine protector roles through Cassar’s bushcraft and warrior ethos while simultaneously inviting nurturing, intuitive feminine identities into the circle through rituals of care, gratitude, and emotional openness. These gendered affective roles contribute to the internal structure of the community and reinforce narratives of balanced, sacred harmony. However, they also mask the settler power dynamics at play, giving the appearance of decolonial healing while reinscribing colonial hierarchies.

Belonging in CEA is constructed through emotional resonance, but also through symbolic exclusion. Indigenous land councils like DLALC are not just bureaucratic adversaries. They are cast as emotional villains, desecrators of sacred ecology, and betrayers of cultural truth. The result is a politics of belonging that requires the rejection of Indigenous authority in order to affirm settler spiritual purity.

As such, the rituals of emotional bonding produce a sense of innocence and moral superiority that forecloses self-reflection. This sacralised boundary between insider and outsider renders dialogue with Aboriginal voices nearly impossible. Any challenge is reframed as an attack on the group’s spiritual identity, leading to further emotional intensification and epistemic closure.

Understanding CEA through this lens reveals the deeper stakes of settler conspirituality. It is not simply a set of false beliefs or environmental misinformation. It is an affective formation, a mode of belonging forged through conspiracy, spiritualised emotion, gendered ritual, and settler mimicry. Disrupting its power requires more than fact-checking. It demands a strategic cultural intervention: one that affirms Indigenous sovereignty while offering counter-narratives of belonging grounded in truth, relational ethics, and cultural accountability.

This could include targeted public discourse campaigns, curriculum interventions through Reconciliation Australia or anti-racism education, and platforming of initiatives such as the Wangan and Jagalingou cultural law assertion strategy. Only by replacing affective manipulation with emotionally resonant truth-telling can the spell of settler spiritual populism be broken.

Section 6: Platforms of Prophecy: Social Media Spectacle and the Rituals of Conspiritual Community

The success of settler conspiritual movements like the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) is inseparable from their use of social media as a platform for digital ritual and spectacle. In these online spaces, spiritual populism converges with algorithmic amplification, turning conspiracy into community and spectacle into belief.

Jake Cassar’s charisma, spiritual rhetoric, and aesthetic curation function synergistically in digital ecologies to create a sacred space of emotional resonance and symbolic warfare.

Cassar’s posts across platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are richly affective. They feature images of sacred trees, sunset vigils, misty landscapes, and ritual gatherings infused with language of spiritual urgency and divine mission.

These digital artefacts are not simply expressive; they are performative, constructing an immersive cosmology in which followers are recruited into an enchanted war for Country.

Kalpokas (2018) calls this dynamic “post-truth aesthetics,” where emotional veracity trumps empirical evidence and where the circulation of affect becomes epistemological proof. As Van Badham (2021) argues, the aesthetic grammar of conspiracy movements like QAnon uses emotionally charged imagery and narrative immersion to override rational critique, a strategy clearly echoed in Cassar’s visual politics.

These online spaces function as affective economies (Ahmed, 2014), wherein emotions are not privately held but publicly exchanged, shaping communal identity through likes, comments, and shares. Followers respond to Cassar’s narratives with grief, rage, reverence, and resolve, reinforcing the spiritual validity of the cause through digital reciprocity. Each interaction becomes a micro-ritual of belonging.

Social media also enables the formation of what Lorenzi (2020) terms “algorithmic kinship”, affective bonds forged through repeated digital engagement. The architecture of the platforms ensures that emotionally provocative content gains greater visibility, creating feedback loops that intensify belief and belonging.

Cassar’s community thus becomes bound not only by ideology but by the shared rhythm of ritualised online activity: livestreams, photo commentaries, story reposts, and call-and-response affirmations.

Cassar’s narrative architecture often mimics liturgical form. Posts begin with expressions of mourning or outrage, proceed through a retelling of sacred violation (such as a DLALC development), and conclude with invocations of resistance, awakening, or love. This para-liturgy converts secular political conflict into spiritual ceremony. His followers are not just observers, they are initiated co-participants in the drama of settler redemption.

This ritual form aligns closely with what Assaf (2011) and Brennan (2019) identify as “white shamanism,” in which settler spiritual practitioners appropriate Indigenous ritual forms to construct an imagined moral and cultural legitimacy.

This ritualisation of online space is deeply political. CEA’s social media engagement produces a binary cosmology: the awakened guardians of sacred land versus the desecrating forces of institutional corruption.

Aboriginal institutions like DLALC are rarely critiqued in nuanced terms. Instead, they are symbolically flattened, rendered as betrayers of Country or spiritually compromised authorities. This discursive violence is all the more potent for being cloaked in reverential language.

Moreover, social media offers a stage for the performance of charismatic authority. Cassar’s digital presence draws on techniques from wellness influencers, New Age spirituality, and activist branding.

His role as “protector” is visually reinforced through imagery of rugged landscapes, ritual engagement, and moments of meditative stillness. His charisma is not static; it is maintained through continuous emotional labour and digital curation.

Cassar’s online mobilisation strategy also draws from QAnon-affiliated aesthetic and emotional logics. As Moskalenko et al. (2021) note, QAnon’s digital rituals rely on communal decoding, spiritualised resistance, and epistemic enclaves reinforced through algorithmic design. Cassar’s followers experience his online presence as a sacred feed, each post a moment of revelation, affirmation, or encoded truth.

Importantly, social media also shields CEA from scrutiny. Attempts at fact-checking or legal clarification are often reinterpreted within the group as attacks on their spiritual identity. This is consistent with the affective logic of conspirituality: truth is not established through reason but revealed through feeling.

Cassar’s followers are emotionally immunised against contradiction, because alternative narratives are experienced not as differences of opinion but as threats to sacred belonging.

Understanding these dynamics reveals the ritual and affective infrastructure of settler conspirituality. Cassar’s use of social media is not incidental, it is foundational. His digital charisma, ritualised storytelling, and emotional curation transform social media into a site of epistemic sovereignty and spiritual mobilisation.

Challenging this formation will require counter-narratives that are not only truthful, but emotionally resonant and culturally grounded in Indigenous law and sovereignty.

Existing platforms such as NITV’s “Truth-telling” series and the Narragunnawali reconciliation curriculum offer models of affective counter-publics capable of resisting the emotional pull of conspiritual narratives.

Section 7: Emotional Communities and the Politics of Belonging

Settler conspiritual movements such as Jake Cassar’s Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) are held together not simply by shared beliefs, but by shared feelings. These movements function as affective communities, where emotions such as grief, awe, betrayal, nostalgia, and righteous indignation are not only expressed but ritualised.

Emotional belonging becomes a political strategy, binding members together in a sacred mission framed as resistance to institutional corruption and desecration of land.

This dynamic reflects what Hochschild (2016) describes as “feeling rules”: implicit norms that guide how emotions should be felt and displayed in specific contexts. Within CEA, these rules prioritise reverence for the land, sorrow over environmental degradation, fear of institutional betrayal, and anger toward those seen as spiritually impure or politically compromised. Crucially, Indigenous organisations like the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) are cast in this emotional schema not as legitimate actors but as spiritual adversaries.

Ahmed’s (2014) concept of the “affective economy” helps illuminate how these feelings circulate within the group. Emotions move between bodies, online posts, protests, and rituals, creating a sense of shared moral clarity. Through chanting, mourning, or gratitude-sharing, followers affirm a collective identity rooted in spiritual guardianship. These rituals are not merely symbolic—they generate solidarity and epistemic insulation. Critique is reframed as desecration; disagreement, as betrayal.

Cassar’s leadership is central to this affective architecture. His personal charisma channels what Weber (1947) termed “charismatic authority,” but inflected through spiritual populism. Cassar models emotional responses, grief for the land, righteous anger toward developers, and serenity in the face of adversity. His followers mirror these affective cues, creating an emotional echo chamber that reinforces belief.

This charisma operates within what Lorenzi (2020) describes as “algorithmic kinship”—digital platforms that reward emotionally engaging content. Through Facebook posts, livestreams, and comment threads, Cassar’s followers engage in collective emotion work. They share testimonies, express awe at sacred sites, and perform spiritual indignation. These acts become affective rituals that strengthen their emotional and ideological commitment. Phillips (2025) adds that such platforms often gamify affect, offering users rewards for emotional intensity and moral certainty, which accelerates group radicalisation.

This emotional infrastructure also intersects with what Assaf (2011) and Brennan (2019) term “white shamanism”: a process by which white spiritual figures claim access to Indigenous knowledge and ritual authority through emotional sincerity and spiritual charisma. Settler conspiritualists like Cassar transform their emotional depth into presumed cultural legitimacy, claiming to ‘feel’ Country more deeply than Aboriginal institutions and asserting themselves as truer custodians.

Moreover, settler emotional mimicry replicates Aboriginal ceremonial modes of grief and reverence while severing them from the political and legal claims of sovereignty. Watego (2021) reminds us that such performances are not benign, they are acts of epistemic violence that reframe cultural authority as a matter of spiritual resonance rather than lawful inheritance. This process often appropriates trauma discourse and therapeutic language—such as “healing,” “holding space,” and “energetic cleansing”—to reframe settler identity as spiritually wounded and therefore entitled to lead restoration.

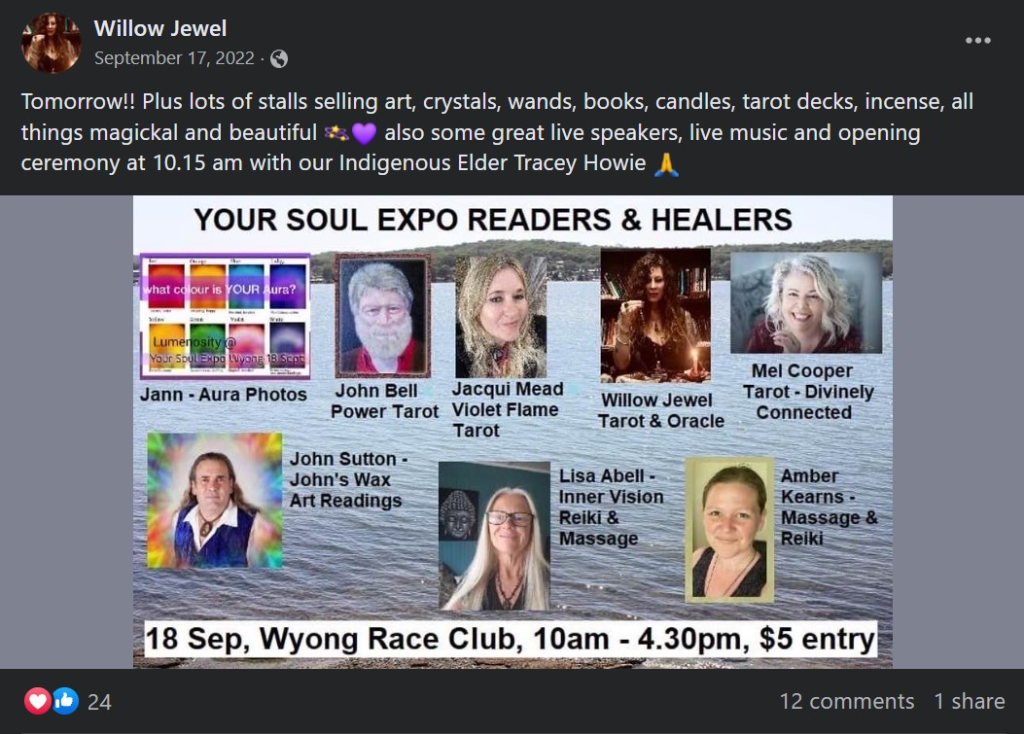

Importantly, the politics of belonging within these emotional communities are gendered. While Cassar’s leadership emphasises rugged masculinity, female figures like Lisa Bellamy and Tracey Howie often deploy maternalist rhetoric and the emotional labour of care. This dual-gendered appeal deepens the emotional pull of the movement and mimics Indigenous kinship frameworks, all while centralising settler authority.

Yet this politics of belonging is also a politics of exclusion. Belonging is defined not only by who is included, but by who is expelled. CEA constructs symbolic boundaries by casting Aboriginal institutions like DLALC as spiritually compromised or politically corrupt. This logic perpetuates what Maddison (2019) calls “white sovereignty,” the ability of settler society to define the terms of legitimate Indigeneity. Aboriginal critique is not engaged with, but disavowed—often under the guise of spiritual protection.

The emotional appeal of settler conspirituality is its greatest strength and gravest danger. It transforms settler longing into sacred mission, allows colonial anxieties to be spiritualised, and mobilises feeling as moral truth. It provides community, purpose, and redemption—while marginalising Indigenous law, authority, and voice.

The next and final section considers what is required legally, ethically, and educationally to reckon with settler conspirituality and re-centre Indigenous authority in the face of such emotionally charged resistance.

Section 8: Conclusion – Reckoning with Settler Conspirituality

The rise of settler conspirituality in Australia, exemplified by Jake Cassar and the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), signals a troubling convergence of spiritual appropriation, conspiratorial populism, and settler-colonial resurgence. These movements cloak settler resistance to Aboriginal sovereignty in the language of sacred stewardship, ecological concern, and emotional authenticity. Their power lies not merely in narrative but in affect—in the capacity to bind communities through shared rituals of grief, wonder, and moral outrage.

This article has traced how settler conspirituality operates as a political theology of white possession (Moreton-Robinson, 2015), remaking colonial entitlement as spiritual duty. Through social media spectacle, charismatic leadership, and the strategic mimicry of Aboriginal cultural authority, movements like CEA displace Indigenous governance while masquerading as its protector. They weaponise emotional sincerity, pseudo-ceremony, and mythic narrative to construct a settler spiritual imaginary (Taylor, 2007) in which land becomes sacred not because of its custodial history, but because of the settler’s awakened feeling.

Cassar’s mobilisation of bushcraft masculinity, ancestral myth, and sacred mission exemplifies what Renner et al. (2023) describe as “apocalyptic manhood”, a gendered fantasy of crisis-driven heroism that reclaims land through affective domination. The CEA’s deployment of maternalist, romanticised, and therapeutic discourse echoes longstanding tropes of white spiritual nationalism and what Assaf (2011) termed “white shamanism.” These dynamics illustrate the entrenchment of post-truth populism (Kalpokas, 2018) in contemporary settler environmental resistance, where subjective feeling is privileged over cultural legitimacy and legal recognition. Together, these processes form a politically potent affective infrastructure that displaces Aboriginal sovereignty with settler belonging.

To reckon with settler conspirituality requires more than exposing false claims or correcting historical distortions. It demands a structural and cultural response. First, public institutions must be trained to recognise and reject settler mimicry. Heritage authorities, planning bodies, media organisations, and education departments need protocols for verifying Aboriginal authority, consulting lawful custodians, and challenging symbolic appropriation. Historical precedents such as the Hindmarsh Island Bridge controversy or resistance to Native Title rulings in Western Queensland, reveal that settler resistance often adopts spiritual or ecological frames to reassert colonial control.

Second, affective counter-publics must be amplified. Initiatives like the Uluru Statement from the Heart, Wangan and Jagalingou’s cultural law assertions, First Nations Digital Media Trusts, Yarning Justice, and land-based cultural healing programs offer emotionally resonant, sovereign-centred alternatives. These are not just policy interventions; they are emotional infrastructures rooted in Indigenous law, kinship, and survival.

Third, education systems must embed critical literacy on conspiracy theory, settler-colonial ideology, and the history of spiritual appropriation. This includes curriculum reforms aligned with frameworks such as digital misinformation literacy programs that equip students to discern between cultural respect and appropriation, between emotion and epistemic legitimacy, and between settler fantasy and Indigenous reality.

Finally, reckoning with settler conspirituality demands ethical courage: to listen to Aboriginal critique, to cede space, to resist the seductions of settler innocence, and to centre Indigenous law as the guiding authority on matters of Country, culture, and ceremony. Only by confronting the emotional economies of settler resistance can Australia begin to decolonise its spiritual imaginary and honour the sovereign futures of First Nations Peoples.

References

Ahmed, S. (2014). The cultural politics of emotion (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

Assaf, S. (2011). White shamanism and the appropriation of Indigenous spirituality. Cultural Survival Quarterly, 35(1), 14–17. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/white-shamanism-and-appropriation-indigenous-spirituality

Cochrane, A., Gillespie, B., & Ross, K. (2024). Hegemonic masculinity and the far-right in Australia: Bushcraft, violence, and settler identity. Australian Journal of Political Science, 59(2), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2024.00000

Cooke, J. D. (2025). The false mirror: Settler environmentalism, identity fraud, and the undermining of Aboriginal sovereignty on the Central Coast of NSW. https://guringai.org/2025/06/06/the-false-mirror-settler-environmentalism-identity-fraud-and-the-undermining-of-aboriginal-sovereignty-on-the-central-coast

Forberg, P. (2021). QAnon and the international far right: How mythology, the internet, and populism fused. Journal of Political Myths, 6(1), 15–29.

Halafoff, A., Singleton, A., Bouma, G., & Rasmussen, M. L. (2022). Freedoms, faiths and futures: Teenage Australians on religion, sexuality and diversity. Bloomsbury Academic.

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. The New Press.

Illouz, E. (2007). Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Polity.

Jake Cassar Bushcraft. (n.d.). About Jake. https://www.jakecassarbushcraft.com.au/about-jake

Kalpokas, I. (2018). A political theory of post-truth. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96559-8

Lorenzi, J. (2020). Algorithmic kinship: Social media rituals and conspiracist belonging. Media and Society, 12(3), 45–61.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Phillips, W. (2025). From LARPing to legislating: The evolution of QAnon in Australia. Media, Culture & Politics, 42(1), 43–62.

Renner, J., Gusterson, H., & Crabtree, S. A. (2023). Apocalyptic manhood and doomsday prepping: Masculinity in crisis. Gender & Society, 37(2), 178–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432221144321

Taylor, B. (2007). Dark green religion: Nature spirituality and the planetary future. University of California Press.

Toscano, A., & Kinkle, J. (2015). Cartographies of the absolute. Zero Books.

Ward, C., & Voas, D. (2011). The emergence of conspirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2011.539846

Watego, C. (2021). Another day in the colony. University of Queensland Press.

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240

Leave a reply to The Conspirituality of Jake Cassar, the Campfire Collective, and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) – Bungaree.org Cancel reply