The “GuriNgai” controversy is one of Australia’s most significant cases of Indigenous identity fraud, showing how colonial misclassification, genealogical fabrication, and institutional failure distort truth and undermine Aboriginal sovereignty. What began as a Northern Sydney, Hornsby Shire, and Central Coast issue has grown into a national example of how epistemic insecurity enables cultural appropriation, policy capture, and settler simulation.

The term derives from missionary John Fraser, who in 1892 expanded the name of the Gringai people north of the Hunter River to construct a speculative “Kuring-gai tribe.” Subsequent scholarship has demonstrated that this category lacks evidentiary foundation. Wafer and Lissarrague (2010) found no reliable colonial attestation of “Kuringgai,” while linguistic research confirms that the authentic Guringay people are located north of the Hunter River in the Barrington–Dungog region, speaking a Gathang dialect distinct from the Sydney Basin languages (Lissarrague & Syron, 2024). The Aboriginal Heritage Office report Filling a Void (2015) likewise concluded that “Kuringgai” is an anachronistic construct later adopted by councils without adequate consultation with recognised custodians.

This conceptual vacuum enabled appropriation. In 2003, Warren Whitfield established the Guringai Tribal Link Aboriginal Corporation, advancing genealogical claims linking himself and others to Bungaree and Matora through the purported “Sophy–Charlotte Ashby” line. Archival and genealogical analysis has refuted this lineage. Between 2007 and 2008, individuals including Tracey Howie, Laurie Bimson, and Neil Evers consolidated public authority by conducting Welcome to Country ceremonies and advising institutions as “Elders.” Councils, schools, and heritage bodies reproduced these claims through signage, acknowledgements, and programming, thereby normalising an unverified identity.

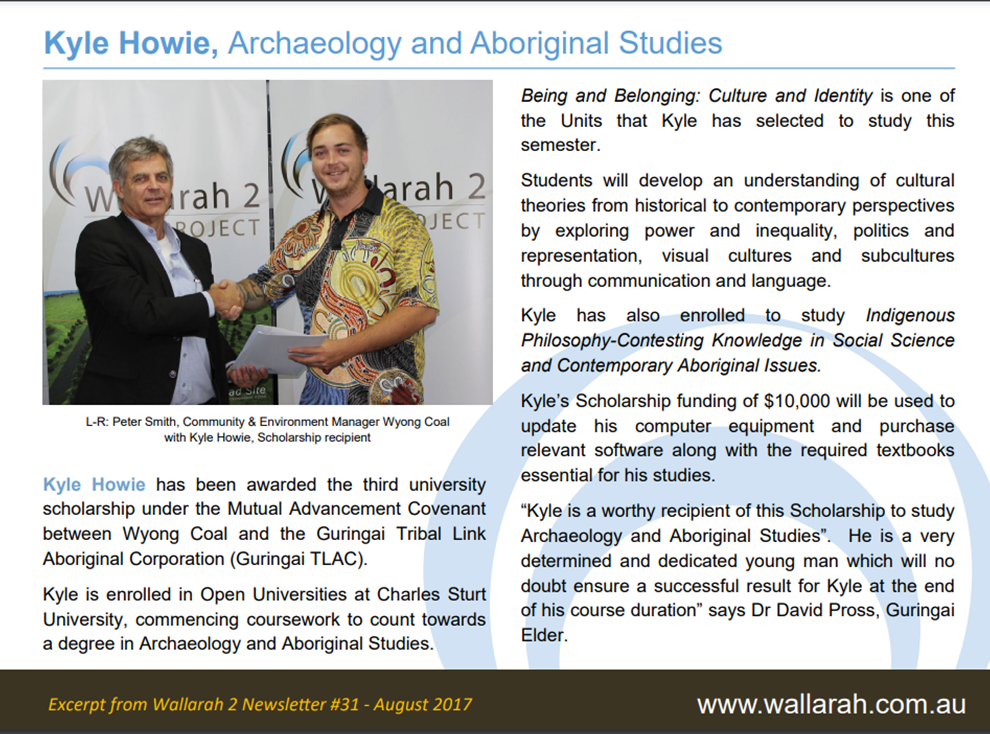

By 2009 to 2016, the network had embedded itself within governance structures, drawing on reconciliation frameworks to legitimise contested status. Partnerships with corporate and environmental actors, including the Coast Environmental Alliance, illustrate how unverified identity claims influenced heritage and planning processes. Although the Aboriginal Heritage Office findings in 2015 intensified scrutiny, institutional reluctance to reassess earlier endorsements prolonged the error.

From 2017 to 2023, Hornsby Shire Council and associated bodies continued to recognise “GuriNgai Country” despite formal objections from Aboriginal Land Councils. Correspondence from Metropolitan, Darkinjung, and other LALCs between 2020 and 2022 affirmed that “GuriNgai” is not recognised under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) and that the historical Guringay are situated north of the Hunter River. The Registrar in 2020 and NTSCORP in 2020 confirmed that no such group held native title or demonstrated verified descent. Nonetheless, institutional usage persisted.

The controversy extended into the arts through the film Nyaa Wa by Charlie Woods, which repeated the discredited Bungaree–Ashby genealogy. Sustained community advocacy prompted corrective action, including the removal of “Guringai” from National Parks and Wildlife signage in 2021. Indigenous-led archival research, supported by linguistic and legal scholarship, has since established a robust evidentiary foundation for rectification.

Meaningful reconciliation requires withdrawal of inaccurate acknowledgements, consultation with recognised Aboriginal People, including Local Aboriginal Land Councils, and transparent public correction. Aboriginal identity does not and can not rest on performance or administrative convenience; it must be grounded in demonstrable descent and Aboriginal community recognition. As affirmed by the Marramarra Carigal community, recognised statutory bodies, the Guringay north of the Hunter River, and community-based research platforms, Northern Sydney, Hornsby Shire, and the Central Coast is not “GuriNgai Country.”

Restoring integrity demands truth telling, institutional accountability, and respect for legitimate custodianship.

JD Cooke

Proud Marramarra Carigal/Garigal man.

Chapter 13. 2023 – Post publication of A Long Con Gone On Too Long.

Addendum. ANTHROPOLOGICAL CONNECTION REPORT: Family history and contemporary connection evidence.

Addendum. A new perspective on Laurence Paul Allen’s thesis.

Addendum. Goolabeen – Saving Kariong ‘Sacred Lands’

Contact the author using the contact form below. If you would like, it’s entirely up to you.