This paper demonstrates that the GuriNgai group and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) operate not merely as fringe community groups but as contemporary cults. They exhibit the core structural and behavioural characteristics of cultic organisations as defined in psychological, sociological, and legal scholarship. Through the appropriation of Indigenous identity, ecological mythologising, and charismatic leadership, these groups reproduce colonial authority under the guise of misguided cultural or environmental protection.

Drawing on a wide range of formal definitions of cults from Langone (1993), Lifton (1989), Lalich (2004), Hassan (2015), Singer (2003), Tobias and Lalich (1994), Richardson (1993), Anthony and Robbins (1992), and Zablocki (2001), this paper demonstrates how both groups employ coercive mechanisms including epistemic closure, charismatic manipulation, ritualised belief enforcement, and myth-based recruitment. These features function to enforce compliance, engineer loyalty, and discredit dissent.

These conspiritualist groups appeal to white guilt, spiritual lack, and ecological anxiety to recruit members, using pseudo-Aboriginal narratives and fabricated genealogies to confer cultural legitimacy.

Their operations are sustained through information control, emotional coercion, and spiritual fraud, constituting a high-control environment that functions like a religion but without traditional ethical boundaries or lineage accountability.

A comprehensive understanding of cults requires engagement with multiple scholarly frameworks, each emphasising distinct mechanisms of control, ideological insulation, and psychological manipulation. These models, drawn from clinical psychology, sociology of religion, and cultic studies, are indispensable for identifying the structural features shared by both the GuriNgai and CEA movements.

Building on recent studies of conspirituality (Ward & Voas, 2011; Halafoff et al., 2022), post-truth epistemologies (Kalpokas, 2019), and settler-colonial mimicry (Veracini, 2010), this paper identifies the GuriNgai and CEA not as aberrant anomalies but as contemporary expressions of white possessiveness (Moreton-Robinson, 2015) and identity theft disguised as justice.

Recognising the GuriNgai and CEA as cultic formations is essential for understanding their tactics, documenting their structural harms, and informing evidence-based interventions that centre Aboriginal self-determination and cultural safety.

2. Defining Cults: Formal Criteria and Theoretical Foundations

To establish that the GuriNgai and CEA operate as cultic organisations, it is essential to engage critically with multidisciplinary definitions of cults. Michael Langone (1993) defines a cult as “a group or movement exhibiting great or excessive devotion to some person, idea, or thing, and employing unethical manipulative techniques of persuasion and control… to advance the goals of the group’s leaders, to the actual or possible detriment of members, their families, or the community” (p. 5). This definition underscores the exploitative structure of groups that use manipulation and devotion to consolidate power.

Robert Jay Lifton’s (1989) framework of “ideological totalism” outlines eight key themes of cultic control: milieu control, mystical manipulation, demand for purity, cult of confession, sacred science, loading the language, doctrine over person, and dispensing of existence. These elements describe how cults engineer cognitive isolation and total commitment through a comprehensive system of belief, language, and behaviour.

Janja Lalich (2004) builds on this with the concept of “bounded choice,” where cult members surrender personal agency through mechanisms of dependency, coercion, and ideological closure. Her notion of a “self-sealing system” captures how criticism and doubt are neutralised internally, preventing escape or critical reflection.

Steven Hassan (2015) contributes the BITE model—Behaviour, Information, Thought, and Emotional control—as a practical diagnostic tool to identify authoritarian cults. He explains how cults systematically regulate members’ physical routines, access to information, cognitive processes, and emotional responses to create conformity and dependence.

Margaret Singer (2003) focuses on thought reform, emphasising techniques such as love bombing, phobia indoctrination, and induced dissociation. These methods are used to destabilise identity and reframe members’ relationships with truth and selfhood.

Additional definitions from Richardson (1993), Anthony and Robbins (1992), and Zablocki (2001) introduce a sociological perspective. They emphasise the dynamics of control through social structure, charismatic authority, role insulation, and the social construction of truth and belonging. Zablocki, in particular, describes cults as groups employing “charismatic authority and strategic social encapsulation” to enforce ideological commitment and isolate followers from competing worldviews.

Together, these frameworks outline the necessary criteria for identifying cultic groups: (1) charismatic leadership and centralised authority, (2) unethical persuasion and manipulation, (3) enforced conformity and epistemic insulation, and (4) harm to members, critics, and the wider society. As subsequent sections demonstrate, the GuriNgai and CEA not only meet but exemplify these characteristics in structure, practice, and impact.

3. Charismatic Leadership and Spiritual Fraud

At the core of all high-control cultic formations lies charismatic authority. Max Weber’s (1947) theory of charisma describes the “exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character” attributed to leaders whose claims are not grounded in traditional or legal-rational legitimacy but in personal mythos and emotional appeal. Both the GuriNgai and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) are organised around such centralised charismatic figures, Tracey Howie and Jake Cassar, whose unverified or demonstrably false claims to expertise, spiritual or cultural knowledge become the primary source of institutional authority within their respective groups.

Tracey Howie self-identifies as an Aboriginal Elder, cultural educator, and law-woman, asserting descent from the so-called “Guringai,” “Wannangine,” and “Walkaloa” clans. These clans have no documented historical basis in anthropological or community-endorsed sources (Kwok, 2015; Cooke, 2025; Bungaree.org, 2025). Howie’s identity claims and associated cultural authority have been systematically challenged by Aboriginal community members, historians, and genealogical researchers. Nevertheless, she maintains public influence through institutional partnerships, educational workshops, and media visibility, leveraging her position to delegitimise genuine Aboriginal authority structures such as the Metropolitan and Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Councils. Her charismatic influence operates in classic cultic fashion: elevating personal narrative above community verification, dispensing with objective genealogical critique, and centring herself as the sole interpreter of “truth” and “law” in local Indigenous affairs.

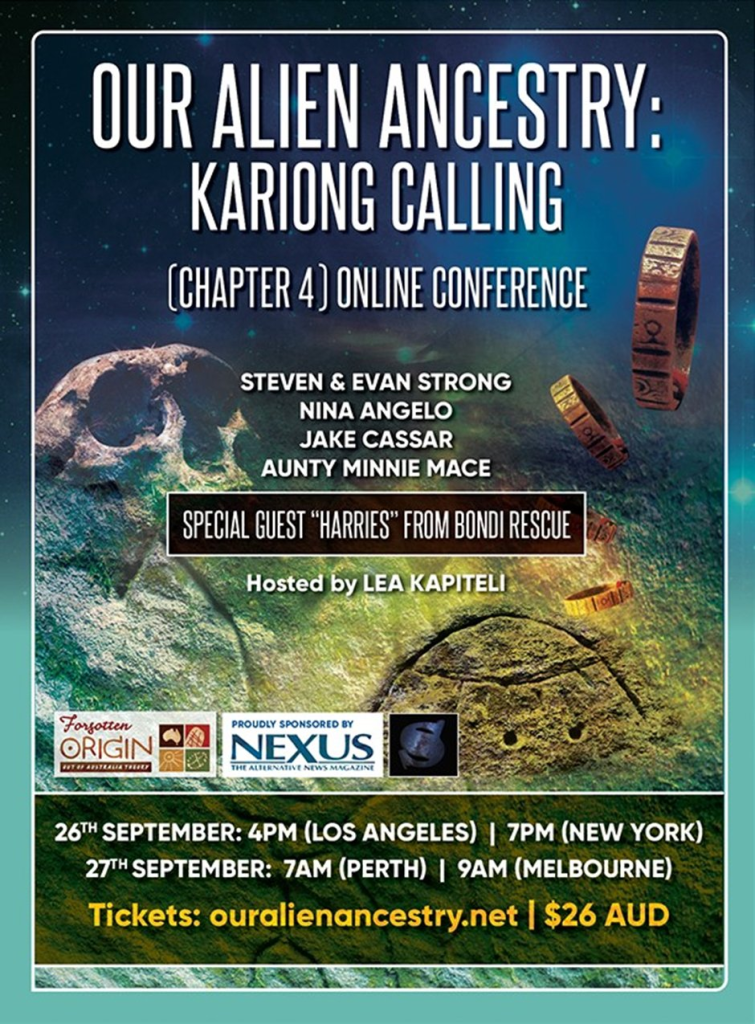

Jake Cassar similarly exercises charismatic dominance, albeit through a spiritualised faux-environmental lens. Presenting himself as a bushcraft expert, conservationist, and protector, Cassar has used his persona to attract a broad social media following and mobilise campaigns exclusively opposing Aboriginal-led developments. He routinely incorporates spiritual language, mythopoetic storytelling, and references to “sacred trees,” “ancient wisdom,” and being “custodians” in describing the lands he claims to defend (CEA, 2023–2025). Yet his campaigns have repeatedly targeted Aboriginal-owned lands and been based on fabricated mythologies, such as the debunked “Kariong Hieroglyphs” or the spiritually charged but culturally unauthenticated “Grandmother Tree.” His leadership mirrors Lifton’s (1989) concept of “mystical manipulation,” wherein leaders manufacture spiritual authority by aligning themselves with supposedly divine or cosmic purpose—thereby rendering dissent not merely wrong but sacrilegious.

Both leaders exercise unilateral interpretive power. Their personal narratives function as sacred science (Lifton, 1989), immune to scrutiny, and their declarations about ancestry, land, and law are treated as inviolable truths within their organisations. Dissent is preemptively neutralised by framing it as racism, cultural ignorance, or government corruption. This epistemic closure is indicative of what Lalich (2004) terms a “bounded choice” environment: followers are presented with only one acceptable interpretive framework, that of the leader, under the guise of cultural or ecological authenticity.

From the perspective of the BITE model (Hassan, 2015), Howie and Cassar enforce Behavioural control (through attendance at rituals, land visits, and protests), Information control (through misinformation about Aboriginal history and land rights), Thought control (by redefining settler guilt as spiritual ancestry or custodianship), and Emotional control (through guilt induction and fear of exclusion). They perform what Tobias and Lalich (1994) describe as “pseudo-tribal” leadership, fostering a closed in-group identity in which traditional relational accountability is replaced with authoritarian loyalty to the central figure.

Importantly, these dynamics are not merely internal. Cassar and Howie’s charisma is projected outward to institutions and public audiences. Local councils, schools, and environmental organisations often collaborate with or platform these individuals, unaware of the fabricated bases of their authority or the coercive nature of their group structures. Their ability to manipulate institutional relationships underscores Richardson’s (1993) emphasis on how cults strategically manage public legitimacy while maintaining authoritarian control internally.

The cultic pattern of centralised spiritual fraud within both the GuriNgai and CEA reflects what Johnson (1967) called the “substitutive ideology” of charismatic movements: the replacement of inherited or verified traditions with fabricated systems designed to reinforce leader control. This not only perpetuates harm within their respective groups but also contributes to the epistemic erasure of legitimate Aboriginal law, heritage, and governance.

4. Mythmaking and Settler Fantasy

Cults do not simply disseminate misinformation; they engineer alternative epistemologies. One of the most insidious forms of this engineering is mythmaking, what Lincoln (1989) refers to as the fabrication of “authorising narratives” that structure belief, identity, and belonging. Within the GuriNgai and CEA networks, mythmaking functions as a central technique of settler cultural production, blending pseudo-history, spiritualised fantasy, and visual spectacle to displace Aboriginal sovereignty and substitute fabricated traditions.

The GuriNgai group has manufactured a cosmology of fictitious clans, such as “Walkaloa” and “Wannangine,” as well as an invented language and mythology with no basis in the historical ethnographic or linguistic records of the Sydney or Central Coast regions (Lissarrague & Syron, 2024). These narratives are disseminated via ceremonies, land acknowledgements, and spiritual education programs which portray white individuals as descendants of Bungaree or “keepers” of the land’s energy. This behaviour reproduces what Deloria (1998) called “playing Indian,” wherein settler desires for rootedness and authenticity are projected onto fabricated Aboriginal identities.

Similarly, CEA’s campaigns are structured around ecological mythologies that invert Aboriginal land rights into threats against sacred white relationships to Country. Jake Cassar’s mythologisation of the “Grandmother Tree” and the Kariong Glyphs exemplifies what Barker (2022) describes as prepper-spiritual fusion narratives, where apocalyptic fears and spiritual destiny converge in the landscape. Despite being debunked as modern graffiti (Coltheart, 2011), the Kariong Glyphs are portrayed by CEA as evidence of ancient truths concealed by governments and corrupt land councils. These myths are not marginal, they are central to the group’s mobilisation strategies.

In the case of the “Grandmother Tree,” a single angophora outside the DLALC’s Kariong development site has been sacralised through ritual performance, livestreamed veneration, and narrative repetition. The tree, lacking Aboriginal cultural validation, becomes a cult object, infused with constructed meaning and defended as if sacred law. This reflects what Comaroff and Comaroff (2009) identify as the commodification of indigeneity: a process where spiritual narratives are extracted from Aboriginal context and refashioned as symbolic capital for settler projects.

These mythologies allow for what Watego (2021) calls “fantasies of cultural benevolence.” Settler participants in the GuriNgai and CEA movements frame their roles not as appropriators but as spiritual custodians resisting modernity and corruption. The actual result, however, is the epistemic erasure of real Aboriginal law, culture, and genealogical authority. In line with Lifton’s “sacred science,” the myths are upheld with cultic rigidity, with any challenge treated as heresy.

These dynamics are further sustained by conspiracist worldbuilding. The groups consistently claim that Aboriginal land councils are “government puppets,” that Aboriginal opposition is “cancel culture,” and that their own myths are “ancient knowledge” recovered through spiritual revelation. This closely mirrors the mechanisms of QAnon, as described by Montell (2021), wherein esoteric symbolism, spiritual warfare, and populist anti-institutionalism are fused into a totalising belief system.

Within the GuriNgai–CEA alliance, this mythmaking serves dual cultic functions: internally, it binds followers to a sense of enchanted destiny; externally, it justifies political attacks on Aboriginal governance. The fantasy of ancient custodianship replaces legal recognition, ritual performance substitutes for kinship, and settler grief is reframed as Aboriginal belonging. This settler spiritual fantasy is not merely appropriative; it is a deliberate tool of recolonisation—one that enacts white possessiveness under the guise of sacred defence.

As the following sections will demonstrate, these myths are not benign fictions. They constitute an ideological infrastructure for recruiting members, extracting resources, and delegitimising Indigenous sovereignty. Mythmaking is thus not peripheral but foundational to the cultic structure of the GuriNgai and CEA movements.

5. Epistemic Control and Behavioural Entrapment

Central to the operation of high-control groups is the monopolisation of truth and reality. Both the GuriNgai and CEA networks exhibit classic features of what Lifton (1989) identified as “milieu control,” a process through which a group limits access to external information while tightly regulating internal discourse. Followers are fed curated information through closed online forums, livestream rituals, in-group storytelling, and mythopoetic teachings that reinforce the group’s cosmology. These systems replace empirical verification with revealed truth.

Within these frameworks, dissent is not interpreted as an invitation to dialogue, but as betrayal. Members who question the fabricated genealogies or false Aboriginal claims made by GuriNgai leaders such as Tracey Howie or Neil Evers are cast as either “government agents,” “colonial sympathisers,” or “spiritually lost.” Similarly, within CEA, those questioning the scientific falsity of the Kariong Glyphs or opposing their slander against Darkinjung LALC are branded as morally bankrupt or complicit in environmental destruction.

The epistemic closure is reinforced through social and spiritual rituals, including ceremonies held at the Kariong site, bushwalks guided by Jake Cassar, and seasonal gatherings under the guise of ecological protection. These events double as indoctrination settings, embedding the group’s mythic narrative within an emotional and affective community experience. As Hassan (2015) and Lalich (2004) describe, such rituals operate as powerful reinforcement mechanisms, particularly when combined with threats of spiritual harm or ancestral shame.

This is not merely a case of misinformation. It is the deliberate replacement of pluralistic knowledge systems with dogma. The groups maintain narrative purity by invoking sacred concepts, such as “Country,” “spirit,” and “law,” while refusing engagement with Aboriginal cultural authority, linguistic accuracy, or legal genealogy. In this sense, they construct what Richardson (1993) termed “bounded ideologies”—totalising belief systems insulated from critical reflection.

Moreover, the use of behavioural control mechanisms is apparent in how members are conditioned to perform settler-Indigenous roles. GuriNgai adherents adopt Aboriginal names, wear symbolic regalia, and speak in faux-Cultural idioms. CEA activists are encouraged to become “guardians” of specific sites, to bear “truths” about suppressed histories, and to evangelise the gospel of Kariong’s glyphs. These performances create a simulacrum of identity and authority that mimics but displaces real Aboriginal law.

The result is a deeply embedded echo chamber. Members become psychologically invested in the mythology and group status, and simultaneously alienated from alternative sources of knowledge. This creates a psychological double bind, what Singer (2003) referred to as the cultic milieu’s emotional trap, where exit becomes not only socially costly but spiritually devastating. Many fear spiritual exile, ancestral betrayal, or public shame if they disengage.

Such epistemic and behavioural entrapment further sustains the political function of these cults. Once enmeshed in these networks, members are not merely misinformed; they are ideologically armed against Aboriginal sovereignty. They become grassroots vectors of disinformation, spreading myths, opposing Aboriginal-led developments, and rallying behind false claims of custodianship. As Montell (2021) and Anthony & Robbins (2004) note, this weaponisation of belief is one of the most dangerous capacities of cults: their ability to transform narrative into action under the illusion of sacred purpose.

In sum, the GuriNgai and CEA movements maintain control not just through overt coercion, but through a sophisticated matrix of narrative closure, emotional allegiance, spiritual manipulation, and behavioural conformity. The next section explores how exit from these groups can be understood and supported through interdisciplinary deprogramming and recovery frameworks.

6. Exit Pathways: Interdisciplinary Models of Disaffiliation and Recovery

Disaffiliating from cultic networks like the GuriNgai and CEA requires more than disengagement from a belief system. As the literature on spiritual abuse (Lalich & Tobias, 2006; Ward, 2022), psychological recovery (Singer, 2003), and post-cult trauma (Kaslon, 2019) makes clear, exit entails confronting the loss of identity, community, spiritual orientation, and meaning. These groups do not simply propagate falsehoods, they engineer moral frameworks that render opposition heretical and exit dangerous.

Survivors of cultic entrapment often experience cognitive dissonance, shame, and isolation upon leaving (Festinger et al., 1956; Weiser, 1974). In the GuriNgai and CEA contexts, ex-members report a loss of spiritual purpose, fear of ancestral reprisal, and difficulty reconnecting with family or community outside the group’s narrative. The trauma of being seduced by false Aboriginality or ecological righteousness, only to discover it was based on fraud, can result in prolonged grief and disorientation.

Effective recovery requires what Lalich (2004) terms “bounded choice disruption”—interventions that expand a former member’s perception of agency, epistemic openness, and moral legitimacy. Therapeutic modalities must include:

- Cultural reconnection: Facilitating meaningful, respectful engagement with legitimate Aboriginal Elders and communities, as a way of restoring epistemic grounding and rebuilding a truthful relationship with Country.

- Trauma-informed therapy: Drawing on frameworks such as Judith Herman’s model of trauma recovery (1992), which emphasises safety, remembrance, mourning, and reconnection.

- Narrative deconstruction: Employing approaches from critical discourse and cult recovery studies to help former members understand how language, myth, and ritual were used to engineer emotional dependence and suppress critical thinking (Anthony & Robbins, 1995).

- Community education: Providing resources for families, local councils, and institutions to recognise the warning signs of cultic ideology and avoid unintentionally reinforcing its claims.

Deprogramming must also address the digital architectures that sustain these cults. The CEA’s Facebook page, for example, functions as a self-reinforcing information silo, algorithmically shielding followers from external critique. Research on post-truth media (Kalpokas, 2019; Schatto-Eckrodt et al., 2024) shows how social media fosters “epistemic bunkers” that deepen radicalisation. Recovery, then, must involve digital detoxification and media literacy training to facilitate epistemic independence.

Importantly, exit support must not come solely from clinical spaces. Indigenous-led cultural safety practices, including yarning circles, cultural mentorship, and Elder-guided reflection, are essential to prevent former adherents from perpetuating settler fantasies under the guise of spiritual healing. The process must be both psychological and decolonial.

Ultimately, these cults exploit spiritual yearning and political anxiety to entrap followers. Exit requires not only undoing these psychic bonds but re-establishing ethical orientation grounded in truth, responsibility, and authentic cultural relationships. The following section analyses the broader social harms caused by the GuriNgai and CEA cults, particularly their impact on Aboriginal land justice, knowledge systems, and intergenerational cultural continuity.

7. Social Harms and the Undermining of Aboriginal Sovereignty

The cultic behaviours of the GuriNgai and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) extend far beyond individual psychological harm. They have profound and ongoing consequences for Aboriginal cultural survival, the legitimacy of Indigenous governance, and the continuity of First Nations knowledge systems. By positioning themselves as spiritual or environmental authorities, these groups engage in what Barker (2022) refers to as “colonial simulation”, a process by which settler actors emulate and replace Indigenous sovereignty through spiritualised mimicry.

The GuriNgai group, for example, has falsely claimed descent from Bungaree and the so-called “Walkaloa” clan, despite exhaustive genealogical evidence to the contrary (Bungaree.org, 2025; Cooke, 2025). These fabricated lineages are then leveraged to interfere in land council processes, influence local council decisions, and assert rights to cultural authority and economic opportunity that rightly belong to Aboriginal peoples with verifiable descent and community recognition.

The CEA, meanwhile, has co-opted Aboriginal ecological language and sacred place-narratives to advance settler environmental campaigns that actively undermine Aboriginal land justice. By opposing legitimate Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) development proposals at Kariong, Kincumber, and Lizard Rock, CEA aligns itself with a long tradition of what Moreton-Robinson (2015) calls “white possessiveness”, the affective and institutionalised belief that white Australians are the rightful stewards of land, even when they claim to do so in the name of ‘mother nature’.

These activities result in several measurable harms. First, they divert media and institutional attention away from authentic Aboriginal leadership, creating a public discourse that privileges settler voices on matters of Aboriginal culture and land. Second, they perpetuate confusion among non-Indigenous Australians, many of whom lack the historical literacy to distinguish between fabricated and legitimate cultural claims. Third, they contribute to the erosion of Aboriginal children’s and youth’s access to intergenerational knowledge, as settler narratives overwrite or displace traditional stories and languages.

The GuriNgai and CEA also contribute to a broader pattern of what Tuck and Yang (2012) have termed “settler moves to innocence.” Their invocation of Aboriginal spirituality and sacred ecology provides a moral shield against accusations of racism or appropriation, allowing them to weaponise their fabricated identity as a defence against scrutiny. This tactic is particularly effective in local government, where officials may lack the tools or courage to interrogate such claims. The result is a policy environment in which cultural imposture is tolerated and even rewarded.

Legal scholars such as Watson (2009) and Fforde et al. (2021) have long warned that the absence of rigorous standards for Aboriginal identity verification in heritage, planning, and cultural consultation frameworks invites such abuse. The GuriNgai and CEA’s manipulation of these systems underscores the urgent need for reform. Cultural authority must not be reduced to performance, sentiment, or self-identification; it must be grounded in verifiable descent, community recognition, and cultural accountability.

In sum, the GuriNgai and CEA operate not just as cults of belief and identity, but as instruments of cultural colonisation. They perpetuate a form of symbolic violence that displaces real Aboriginal presence with settler simulation, undermines lawful Aboriginal authority, and weakens the institutions designed to protect Indigenous rights. The final section outlines recommendations for policy, education, and community response to dismantle these cultic infrastructures and re-centre Aboriginal sovereignty.

8. Recommendations: Dismantling Cultic Structures and Recentring Aboriginal Sovereignty

To effectively respond to the harms inflicted by the GuriNgai and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), a comprehensive, multi-sectoral strategy is required—one that addresses both the cultic structure of these groups and their settler-colonial functions. This final section provides a series of interlocking recommendations across law, policy, education, and community practice, aimed at dismantling the social, psychological, and institutional scaffolding that enables these cults to persist.

A. Legislative and Governance Reform

Australian governments at all levels must institute rigorous identity verification standards in all contexts where Aboriginal cultural authority is invoked. This includes heritage assessments, land-use planning, education, and government consultation. Drawing from recommendations advanced by Fforde et al. (2021), reforms should:

- Mandate that cultural consultants and claimants in formal processes demonstrate verifiable genealogical descent from historical Aboriginal communities connected to the land in question.

- Require community recognition from appropriate Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, such as Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs), not just self-identification or endorsement from other claimants with unverified status.

- Establish penalties for misrepresentation of Aboriginal identity in cultural, academic, and policy settings, similar to frameworks in place for academic fraud and professional misconduct.

B. Cultural Safety and Accountability in Local Government

Local governments, such as Hornsby Shire Council and Central Coast Council, must be held to account for platforming fraudulent Aboriginal groups and granting them cultural authority. Cultural safety training must be expanded to include content on identity fraud, cultural appropriation, and settler mimicry. Councils should be required to:

- Conduct independent Aboriginal stakeholder mapping in consultation with state-recognised Aboriginal peak bodies.

- Suspend all cultural heritage, naming, or planning consultations with groups whose identities or claims have been disputed by established LALCs or Aboriginal communities.

- Publicly review their historical and ongoing partnerships with groups such as the GuriNgai, and issue formal retractions or apologies where necessary.

C. Media Ethics and Public Discourse

Mainstream and independent media outlets—including Coast Community News—must cease the uncritical amplification of false Aboriginal narratives and instead adopt journalistic standards that centre authentic cultural authority. This includes:

- Verifying genealogical claims before platforming cultural spokespersons.

- Including commentary from LALCs or First Nations scholars when reporting on contested claims of identity, culture, or land.

- Avoiding language that legitimises fabricated groups (e.g., calling GuriNgai a “tribe” or “nation”) without acknowledging the absence of legal or historical basis.

D. Educational Curriculum and Public Literacy

Educational institutions must revise curriculum content to include discussions of identity fraud, cultural appropriation, and the politics of authenticity in settler-colonial societies. Cultural literacy programs should be developed in collaboration with Aboriginal educators to:

- Equip students and the broader public to recognise and reject settler spiritual mimicry.

- Promote respectful engagement with legitimate Aboriginal knowledge holders.

- Foster critical media and historical literacy regarding Aboriginal identity, colonialism, and institutional complicity.

E. Cult Recovery and Support Services

Given the documented psychological manipulation used by GuriNgai and CEA (see Hassan, 2015; Lalich, 2004), there is a clear need for cult recovery services specifically tailored to individuals exiting settler-conspiritualist environments. This support must include:

- Trauma-informed counselling grounded in decolonial and culturally safe frameworks (Wilkins & Toliver, 2022).

- Peer-led recovery groups facilitated by cult survivors and cultural mentors.

- Public rehabilitation campaigns that affirm the legitimacy of leaving high-control spiritual or conspiracist groups, while offering pathways to reconnect with truth, community, and healing.

F. Aboriginal-Led Oversight and Policy Development

All policy development in this space must be led by Aboriginal people and organisations with demonstrable cultural legitimacy and community accountability. This includes:

- Funding and resourcing for Aboriginal-led investigations into identity fraud, with outcomes feeding into government policy.

- Empowering LALCs and Aboriginal peak bodies to maintain accurate registers of legitimate cultural knowledge holders and community genealogies, protected by strict data sovereignty protocols.

- Legislating mechanisms for Aboriginal communities to challenge false claims and receive formal redress, including the reallocation of resources and the removal of inauthentic claimants from boards, committees, or grant recipients.

Conclusion

The dismantling of settler cults such as the GuriNgai group and CEA requires far more than exposure. It demands structural transformation: of law, discourse, governance, and cultural practice. Only through such reforms can the symbolic violence of cultural imposture be halted, and Aboriginal sovereignty reasserted on just terms. The path forward must be Aboriginal-led, historically grounded, and structurally accountable. Anything less is complicity in a new wave of settler colonisation masquerading as reconciliation.

References

Anthony, L., & Robbins, T. (2004). Conversion and “brainwashing” in new religious movements. In L. J. Miller (Ed.), The encyclopedia of cults, sects, and new religions (pp. 119–122). Prometheus Books.

Barker, M. (2022). Awakening from the sleep-walking society: Crisis, detachment and the real in prepper awakening narratives. Journal of Extreme Beliefs, 3(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.c8797fd5

Fetterman, A. K., et al. (2019). On post-apocalyptic and doomsday prepping beliefs: A new measure, its correlates, and the motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.006

Fforde, C., Bamblett, L., Lovett, R., Gorringe, S., & Fogarty, B. (2021). Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity project. AIATSIS. https://aiatsis.gov.au/publication/116456

Hassan, S. (2015). Combating cult mind control (3rd ed.). Freedom of Mind Press.

Johnson, D. P. (1967). Religious and social orthodoxy: The role of political ideology in defining group boundaries. American Sociological Review, 32(5), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092012

Lalich, J. (2004). Bounded choice: True believers and charismatic cults. University of California Press.

Richardson, J. T. (1993). Definitions of cult: From sociological-technical to popular-negative. Review of Religious Research, 34(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/3511987

Singer, M. T., & Lalich, J. (1995). Cults in our midst: The hidden menace in our everyday lives. Jossey-Bass.

Stolz, J., & Toscano, M. (2021). The social construction of charismatic authority in the age of digital reproduction. Journal of Sociology, 57(2), 338–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783321997125

Van Prooijen, J. W. (2017). Connecting the dots: Illusory pattern perception predicts belief in conspiracies. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2266

Wilkins, A., & Toliver, S. R. (2022). Spiritual abuse among cult ex-members: A descriptive phenomenological psychological inquiry. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 23(1), 27–45.

Leave a reply to Prepping For A Doomsday of His Own Making – Bungaree.org Cancel reply