On December 3, 2025 Jake Cassar released his long discussed book, ‘The Cave’.

Introduction: The Text as Radicalizing Infrastructure

In the evolving landscape of contemporary extremism and settler-colonial resistance, cultural artifacts including memoirs, manifestos, and semi-fictionalized narratives, often serve as far more than entertainment; they function as operative mythopoeia.

These texts are designed to construct a shared reality, establish charismatic authority, and provide a blueprint for high-demand groups (HDGs). This report provides a definitive, exhaustive analysis of The Cave, a manuscript authored by Jake Cassar, examining it not merely as a literary work but as an ideological instrument that synthesizes radical environmentalism, conspiratorial ideation, and alternative spirituality—a triad increasingly recognized by sociologists as “conspirituality.”

The Cave operates at the intersection of autobiography, fantasy, and political manifesto. While ostensibly a narrative about a man’s abduction by Yowies in the Central Coast bush, further analysis reveals a sophisticated mechanism for “settler simulation”—a strategy wherein non-Indigenous actors construct a claim to land and spiritual authority that bypasses and displaces legitimate Aboriginal sovereignty.

By situating the protagonist—a thinly veiled author-insert—as the “bridge” between a fallen humanity and a superior, ancient species, the text establishes a foundational myth for the charismatic leadership observed in Cassar’s real-world organizations: the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), the Campfire Collective, the Save Kariong Sacred Lands campaign, the Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign, and the associated “GuriNgai” identity movement

The significance of The Cave cannot be overstated when viewing the operational dynamics of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and its associated entities.

The text provides the theological and ideological justification for the obstructionist tactics employed by these groups against multiple Aboriginal People and organisations, including the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC).

Where the CEA presents a public face of “concerned environmentalism,” The Cave reveals the esoteric underpinnings of this activism: a belief in a coming apocalyptic “Reckoning,” the demonization of modern human society as “termites,” and the elevation of the “Gurunthian” or “Yowie” lineage as the true, superior custodians of the earth.

This analysis dissects the narrative architecture of The Cave, exploring how it weaponizes the aesthetics of the Australian bush to validate a worldview that is fundamentally anti-humanist, eugenicist, and authoritarian.

We examine the mechanisms of control depicted within the text—trauma bonding, chemical indoctrination, and information control—and situates them within the broader discourse of radicalization and the “cult of settler sovereignty.

Furthermore, this report explicitly links the narrative devices of the book to the real-world activities of the CEA, Save Kariong, and Save Kincumber campaigns, demonstrating how the fiction serves as a “sleeper agent” rational for infiltrating political systems and disrupting

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal governance.

The report proceeds through a rigorous deconstruction of the text’s primary archetypes and theological inversions, followed by a detailed mapping of how these concepts are

operationalized in the Central Coast region of New South Wales.

It argues that The Cave is a manual for the dismantling of the modern self and its reconstruction into a “warrior” identity subservient to a localized, genocidal cosmology, designed to recruit disenfranchised individuals into a movement that fundamentally undermines the sovereignty of First Nations people while claiming to protect our heritage.

The Charismatic Leader and the Messianic Complex

Central to the formation of any high-demand group is the establishment of the leader’s mythic status. The Cave serves as the foundational myth for Jake Cassar’s persona, constructing a narrative where his authority is derived not from democratic consensus, peer

review, or traditional education, but from direct anointing by “ancient” and “supernatural” forces.

This myth-making is essential for the cohesion of his follower base across the CEA and Campfire Collective, as it positions his political directives as spiritual imperatives.

2.1 Constructing the Chosen One

The protagonist is identified early in the text as a “chosen one,” a standard trope in cultic milieus designed to isolate the leader from critique and establish an “axis mundi”—a central point connecting the mundane world to the divine.

The Yowies, represented as possessing superior strength, telepathic abilities, and ancient wisdom, specifically target the protagonist because “we know you, and we want to know you better”

This selection process serves distinct sociological functions within the high-demand group structure:

● Validation of Grandiosity:

It validates the leader’s inherent sense of specialness. The

text asserts that the protagonist has “leadership potential” that the Yowies—and by extension, the natural world itself—desperately need.

This mirrors the rhetoric used in CEA campaigns, where Cassar positions himself as the only one brave enough to “speak for the trees” or defend the “sacred lands” against the perceived corruption of the Land Council.

● Cosmic Destiny:

By labeling him the Baah-Boraahk (The Bridge), the text positions the leader as the sole conduit of salvation. Access to the “new world order,” understanding of the “Lore,” or survival of the coming apocalypse is contingent upon proximity to the leader who holds this bridge.

The term Baah-Boraahk is pseudo-Indigenous linguistic

fabrication, appropriating the phonetics of Aboriginal languages to lend unearned gravity to the title.

This archetype elevates the protagonist beyond the status of a mere activist or bushman. He becomes an ontological necessity. As the “Bridge,” he is the only entity capable of mediating between the destructive “termite” nature of humanity and the “sacred” violence of the

Yowies.

This mirrors the structure of charismatic authority described by Max Weber, where the leader’s legitimacy rests on “supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities”.

In the context of the Save Kariong and Save Kincumber campaigns, this archetype allows Cassar to overrule legitimate environmental, and cultural heritage assessments; his “spiritual connection” as the Baah-Boraahk supersedes their legal and ancestral authority.

2.2 The Rejection of Modern Masculinity and Physical Transmutation

The text constructs a specific model of masculinity that is reactionary, “atavistic,” and deeply rooted in the aesthetics of the “manosphere” and the emerging “conspiritual” wellness space. The protagonist begins as a “young bloke following his head and his heart from place to place,” a “drifter” lacking purpose. Through his abduction and initiation, he is transformed into a figure of primal violence and stoicism.

This transformation is explicitly physical and serves as a template for the “super-soldier” fantasy common in far-right and survivalist circles. After consuming “the tea” and undergoing a violent physiological “detox,” the protagonist describes his body: “My body felt bulky but shredded and incredibly powerful… I took in another series of deep breaths and could tell my lung capacity had increased by at least a third”.

This fixation on physical transmutation, becoming the Übermensch, appeals to disenfranchised young men seeking physical agency in a world where they feel powerless. The leader is not just spiritually advanced; he is physically optimized, genetically superior to the “weak” men of modern society.

The narrative reinforces this hierarchy through the “Cave Colosseum,” where physical combat determines value. The protagonist’s ability to hold his own against the massive Yowie warrior Aarkiin validates his status not just as a diplomat, but as a dominant physical force.

This dual competency—spiritual insight combined with lethal capacity—is a hallmark of “warrior monk” archetypes seen in various extremist ideologies.

It also mirrors Cassar’s real-world branding as a “survivalist” and “tracker,” using physical competence in the bush to imply competence in spiritual and political leadership. The “survival missions” mentioned in his bio, where he claims to live off the land for weeks, are the real-world ritual enactment of this textual transformation.

Mechanisms of Control: The “Cave” as a Total

Institution

Sociologist Erving Goffman defined a “total institution” as a place where like-situated

individuals, cut off from the wider society, lead an enclosed, formally administered life. The “Cave” in Cassar’s narrative fulfills the structural criteria of a total institution and a coercive persuasion environment (brainwashing).

This fictional environment serves as an allegory for

the psychological enclosure created within the Campfire Collective and the inner circle of the CEA.

3.1 Abduction and Trauma Bonding

The narrative begins with a violent violation of autonomy: abduction. The protagonist is paralyzed by a dart, slung over a shoulder, and carried into the wilderness.

This mirrors the “isolation” phase of cult indoctrination. The victim is removed from their support network,

their technology (mobile phone) is destroyed or lost, and they are rendered physically dependent on their captors for basic survival needs like food and water.

The psychological dynamic that ensues is a textbook example of trauma bonding (Stockholm Syndrome). Despite the “putrid stench” of the Yowies—described viscerally as a mix of “human faeces, urine, rotten flesh, and body odour”—the protagonist quickly develops an

intense affinity for them.

He describes the abductor, Gymea, looking at him with “kind, almost human eyes” shortly after kidnapping him.

This rapid reframing of abuse as “care” is essential

for retaining members in high-demand groups who suffer harsh conditions; the captive interprets the cessation of violence or the provision of basic sustenance as an act of

benevolence.

In the real-world context of the Campfire Collective and CEA, this dynamic is subtler but structurally similar. Followers are encouraged to isolate themselves from “mainstream media” and “corrupt institutions” (the isolation phase), and are brought into an emotionally charged environment where fear of ecological collapse or government tyranny is whipped up, only to be soothed by the community and leadership of Cassar (the benevolence phase).

3.2 Sensory Deprivation and Epistemic Re-calibration

The training regimen described in the text relies heavily on manipulating sensory input to induce altered states of consciousness and destabilize the recruit’s grip on objective reality. The protagonist is subjected to “sensory deprivation games,” where he is blindfolded, his ears

and nose plugged with “paperbark and native beeswax”

This practice serves a dual purpose in the radicalization process:

- Disorientation: It severs the recruit’s connection to the outside world and their own sensory baseline, making them entirely reliant on the leader’s guidance for navigation and interpretation of reality.

- Epistemic Re-calibration: When the senses are allowed to return, they are “hyper-tuned” to the group’s reality. The protagonist claims to develop a “sixth sense” and the ability to “taste the air like a snake”.

This creates a subjective reality where the group’s supernatural claims feel empirically true to the recruit because their sensory processing has been fundamentally altered. The world is literally perceived differently, reinforcing the leader’s doctrine that the outside world is “asleep” or “blind”.

This mirrors the “red-pilling” terminology used in the sovereign citizen and QAnon networks Cassar aligns with, where initiates believe they have awakened to a hidden

reality.

3.3 Psychopharmacology: “The Tea” as Chemical Gnosis

Perhaps the most critical mechanism of control in The Cave is the continuous administration of psychoactive substances, euphemistically referred to as “the tea.” This substance is not merely a beverage; it is a technology of control and “chemical gnosis”.

The tea is also framed as a tool of eugenics. It is explicitly stated that the tea is a “test of strength” and that the clay figures in the shrine represent people who “got sick in the mind” or died because they were not strong enough to handle it. This Darwinian filter ensures that surviving members feel elite and superior (“The Privileged Ones”), while dissidents or dropouts are framed as biologically inferior, justifying their expulsion or death.

4. Conspirituality: The Inverted Cosmology of Yar-way

and Sephraan

The theological framework of The Cave is a paradigmatic example of “conspirituality”—the fusion of the “New Age” search for spiritual meaning with the “conspiracy theory” focus on hidden global cabals.

It appropriates Judeo-Christian terminology (“Yar-way” for

Yahweh/God, “Sephraan” for Satan/Lucifer) but inverts and distorts their moral associations to suit an eco-fascist worldview.

This theological scaffolding is crucial for understanding the “spiritual warfare” rhetoric used by the CEA against the Darkinjung LALC.

4.1 The Demonization of Humanism (Sephraan)

In Cassar’s cosmology, “Sephraan” (Lucifer) is not the embodiment of evil in the traditional sense, but the embodiment of humanism, individualism, liberalism, and the arts. Sephraan is described as a “rockstar” alien diplomat who advocated for freedom of expression, sexuality, and the preservation of humanity despite its flaws.

Crucially, the text links Sephraan to modern “soft” spirituality and pacifism. The character Bill argues that figures like “Buddha and Ghandi” were established by the “Son of Sephraan” and that “New Age religion” is a tool of pacification designed to keep humanity weak.

This is a profound insight into the group’s radicalization trajectory: it explicitly rejects peace, pacifism,

and humanitarianism as demonic tricks. The “love and light” of New Age spirituality are reframed as mechanisms of control that prevent the “necessary” violent cleansing of the earth.

This mirrors the rhetoric of the “Freedom Movement” which often disparages “woke” culture and humanitarianism as tools of globalist control.

4.2 The Valorization of Authoritarianism (Yar-way)

Conversely, “Yar-way” (God) is depicted as a cosmic authoritarian who is “infuriated” by human behavior and demands “sacrifice for the greater good”. The text explicitly aligns the Yowies with Yar-way’s desire to “destroy the majority of humans”.

This cosmology provides a theological license for genocide. If the “Creator” (Yar-way) desires

the destruction of humanity to save the biosphere, then the Yowies (and the protagonist) are holy warriors executing a divine mandate. This removes moral agency from the killer; they are merely instruments of “The Law.”

The text constructs a “closed ideological loop” where

violence is not a choice but a cosmic necessity. This logic underpins the eco-fascist tendencies of the CEA, where the protection of “nature” (defined by settler terms) justifies the violation of human rights (Aboriginal land rights).

4.3 Ancient Aliens and the “Timeline”

The text incorporates “paleo-contact” theory, asserting that “spaceships” and “sky people” were responsible for wiping out the dinosaurs and seeding life.

The “Timeline” engraved on the cave wall serves as the group’s scripture, providing an alternate history that supersedes scientific consensus. This serves two critical functions:

- Displacement of Science: It replaces evolutionary biology with a hidden history known only to the group, creating an “epistemic tribe” separated from mainstream society. 1 This aligns with the anti-science stance of the sovereign citizen and anti-vax movements Cassar is affiliated with.

- Legitimizing Hierarchy: The Yowies are framed as descendants of these ancient star-gods, making them genetically superior to humans. The protagonist, by being accepted into their fold and consuming the fruit of the Baah-boraahk tree, transcends his human status and joins this elite lineage.

- Eco-Fascism: The Necropolitics of “The Reckoning”

Eco-fascism is the theoretical synthesis of environmentalism and authoritarian nationalism/racism. The Cave acts as a manifesto for this ideology, arguing that the ecological survival of the planet is incompatible with the continued existence of modern human civilization and that a violent “culling” is necessary.

5.1 Dehumanization Rhetoric

The text systematically dehumanizes humanity. Humans are referred to as “termites eating at the foundation of our home” and a “plague”. This insectile imagery is a classic propaganda technique (seen in Nazi Germany and Rwanda) used to overcome the natural inhibition against killing.

If humans are termites, then extermination is not murder; it is structural maintenance. The metaphor strips humans of their individuality and moral status, reducing

them to a destructive biomass. In Cassar’s real-world activism, this rhetoric translates to the framing of the Darkinjung LALC as “developers” and “destroyers,” stripping them of their cultural identity and reducing them to an environmental threat.

5.2 The “Reckoning” Vision

The protagonist experiences a vision of the future—”The Reckoning”—which serves as the group’s eschatology. In this vision, society collapses, and the Yowies hunt down the survivors. The description is graphic and celebratory: “They hunted as a reckoning. As if they had waited

centuries to deliver justice… Children were silenced. Elders crumpled like paper. Nobody was left to rot. Every victim was taken, prepared, and consumed”.

This passage is critical. It does not depict a tragic collapse, but a righteous one. The consumption of the victims transforms the act of killing into a sacred ritual (“Every victim was taken, prepared…”).

The text frames this cannibalism/predation as “balancing the ecosystem”. The Yowies act as the immune system of the planet, eliminating the human virus.

5.3 Eugenics and the “Privileged Ones”

The song sung during the celebration explicitly creates a caste system: “We are the privileged ones who know the sacred… We have tea to make you strong, fast, smart… And tea to make your bones as hard as stone”.

Access to the “tea” and the Yowie knowledge creates a genetic aristocracy. The “Privileged Ones” are those chosen to survive the apocalypse, while the “weak” (mainstream humanity) are fuel for the fires of the new world. The text mentions “missing persons” and “raised

scale-like scars” on the human initiates found in the cave, implying that the group engages in violent hazing and culling of its own recruits. This internal eugenics mirrors the external desire for a population cull.

5.4 The “Cave Colosseum”: Institutionalized Violence

Violence is not just a means to an end; it is a cultural value within the group. The “Cave Colosseum” scene depicts forced gladiatorial combat. The protagonist witnesses a human woman being beaten into unconsciousness by an Epu Gogu, her face smashed with a “hammer fist,” while the crowd cheers.

This institutionalized violence serves to:

- Desensitize: Recruits become numb to suffering, viewing it as entertainment or sport.

- Enforce Hierarchy: Physical strength is the only metric of value. The weak are beaten;

the strong survive. - Trauma Bond: The shared experience of inflicting and receiving pain creates a deep,

perverse solidarity.

6. Indigenous Appropriation: The “Super-Indigene”

Strategy

A central pillar of the text’s legitimacy is its claim to Indigenous wisdom. However, structurally, the text engages in a profound erasure of actual Indigenous Australians, replacing them with the Yowie and the white protagonist in a strategy of “settler simulation”.

6.1 The Yowie as Supersessionist Myth

The text claims that Yowies “were here a lot longer” than humans and that they “taught” the local tribes (Guringai, Darug, Darkinoong) how to live. This narrative device strips Indigenous people of their agency and intellectual property. It suggests that Indigenous knowledge is

actually Yowie knowledge. Since the protagonist is the Yowie’s chosen apprentice, he effectively outranks living

Indigenous elders. He possesses the “source code” of the culture, whereas modern Aboriginal people are depicted as having lost or corrupted it. The author claims to have “worked with Traditional Custodians,” yet creates a fictional hierarchy where the Yowies (and himself) sit

above them. This is the mechanism of “settler nativism”—creating a pre-Indigenous lineage that the settler can access directly, rendering actual Indigenous sovereignty obsolete.

6.2 Linguistic Theft and “Gurunthian”

The text invents a pseudo-language that mimics the phonetics of Australian Aboriginal languages to sound “authentic.” Terms like Baah-boraahk, Waraahn-jeena, and Darnawinan are constructed to appropriate the sonic authority of ancient language. This is “linguistic blackface”—adopting the texture of indigeneity to sell a white man’s fantasy of power. Critically, the text uses the contested term “Guringai” to ground the story. This inserts the narrative into a real-world identity fraud controversy, where non-Aboriginal groups claim “Guringai” heritage to oppose legitimate Land Councils.

By validating this term in his “myth,” Cassar provides ideological cover for these fraudulent claims. The text’s use of “Guringai” is not accidental; it is a political act that aligns the fictional narrative with the real-world GuriNgai group’s efforts to displace genuine Aboriginal People and organisations.

6.3 The “Snake People” and Antisemitic Coding

The text refers to white colonizers as “Snake People” because of their “hissing” sound (the letter ‘s’). While ostensibly an anti-colonial critique, this overlaps dangerously with “Reptilian” conspiracy theories (popularized by David Icke), which often serve as coded antisemitism. The text connects these “Snake People” to “Sephraan” (Lucifer) and financial systems (“dollar symbol”), invoking tropes of a global, satanic, financial elite often found in far-right conspiracy discourse.

This links the eco-fascist narrative to the broader Freedom Movement” and sovereign citizen ideologies.

7. Gender and Sexuality: The Breeding of the New

Race

While the text focuses heavily on masculine strength, its treatment of gender reveals a deeply regressive structure typical of patriarchal cults.

7.1 Yaana: The Fetishized Servant

The primary female character, Yaana, is depicted as a “plump but very muscular” nurturer who is “disturbed” by the violence but ultimately subservient to the male leaders (Pee-dar and Gymea). She is the provider of food and tea, the emotional cushion for the protagonist. The

text sexualizes her (“voluptuous,” “visible breasts,” “seductress”), projecting a Western male gaze onto the Indigenous-coded body.

Yaana functions as the “Mammy” archetype—the non-threatening, nurturing figure who exists to comfort the white master/protagonist. Her resistance to the protagonist’s “testing” (fight to the death) is dismissed by the male hierarchy until she appeals to the logic of violence (proving strength). She is denied the stoic authority granted to the male elders.

7.2 The Epu Gogu and Sexual Dimorphism

The violence of the female Epu Gogu in the Colosseum suggests that women are valued only insofar as they can adopt the violent traits of the males. However, the text also hints at “interrelationships” between humans and Yowies in the past, and the protagonist’s integration

into the tribe carries distinct sexual undertones (the “intimate thoughts” regarding Yaana).

This implies a “breeding program” objective—creating a hybrid lineage to repopulate the earth, a common obsession in white supremacist and Aryan cults.

8. The Return to Society: The Sleeper Agent Doctrine

The final section of the report deconstructs the most dangerous aspect of The Cave: the protagonist’s return to the modern world. Unlike the “Hero’s Journey” where the hero returns with an elixir to heal society, the protagonist returns as a saboteur.

8.1 Infiltration and Political Camouflage

Upon returning, the protagonist does not flee to a cabin. He integrates. He runs for political office as an independent candidate,” works as a “nightclub bouncer” (maintaining physical violence capacity), and engages in “environmental campaigns”.

“I navigated my way through four major political elections… I also made enemies in high places… infiltrated by those who sought to divide and conquer.”

This describes a “sleeper agent” strategy. The protagonist uses the “photographic memory” and “legal knowledge” gained from the Yowies (the Tea) to outmaneuver the system from within. This mirrors the “entryism” tactics used by political extremist groups and sovereign citizens who use “pseudolaw” to disrupt governance. The character’s real-world parallel, Jake Cassar, similarly runs as an independent and leads the CEA, using environmentalism as a cover for anti-institutional disruption.

8.2 The “Author’s Note” and Reality Blurring

The “Author’s Note” is a critical component of the radicalization mechanism. Cassar explicitly states: “The characters in this book are fictitious… [but] Friends are already borderline harassing me to find out which parts of my story are fact and which parts are fiction”.

He then claims that he has had real encounters and that the book expresses his “hopes, dreams, and aspirations for the future of humanity”.

By blurring this line, the text invites the reader to treat the eco-fascist ideology not as a plot point, but as a valid political roadmap. The “fiction” label becomes a liability shield, while the “non-fiction” cues signal to the true believers that the manifesto is real. This technique, known

as “hyperstition” (fictions that make themselves real), is a potent tool in conspirituality.

9. Real-World Manifestations: The Ecosystem of

Displacement

The ideology constructed in The Cave is not contained within the book; it is operationalized through a network of real-world organizations led or influenced by Cassar. This section details how the fiction of The Cave is enacted through the Coast Environmental Alliance, the Campfire Collective, and specific campaigns against Aboriginal land rights.

9.1 Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and Obstructionism as Spiritual Warfare

The Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), founded by Cassar, functions as the political arm of the ideology presented in The Cave. While identifying as an environmental group, its

operational focus is overwhelmingly directed at opposing developments by the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC).

The CEA engages in “green-cladding”—using environmentalism to mask a political agenda of

settler control. By framing the Darkinjung LALC as “developers”, the CEA inverts the colonial power dynamic, casting the Indigenous land owners as the “oppressors” of the land and the white settlers (led by Cassar) as its “protectors”. This is a direct application of the Yowie supersessionist myth found in The Cave, where the “ancient” (white-accessed) lineage trumps the “modern” Aboriginal one.

9.2 Save Kariong Sacred Lands: The Grandmother Tree and

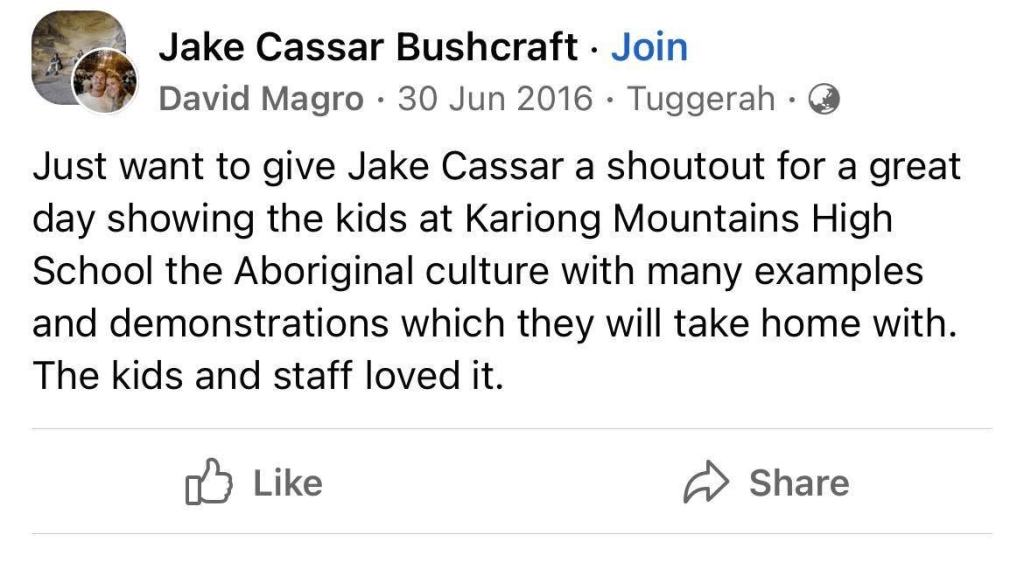

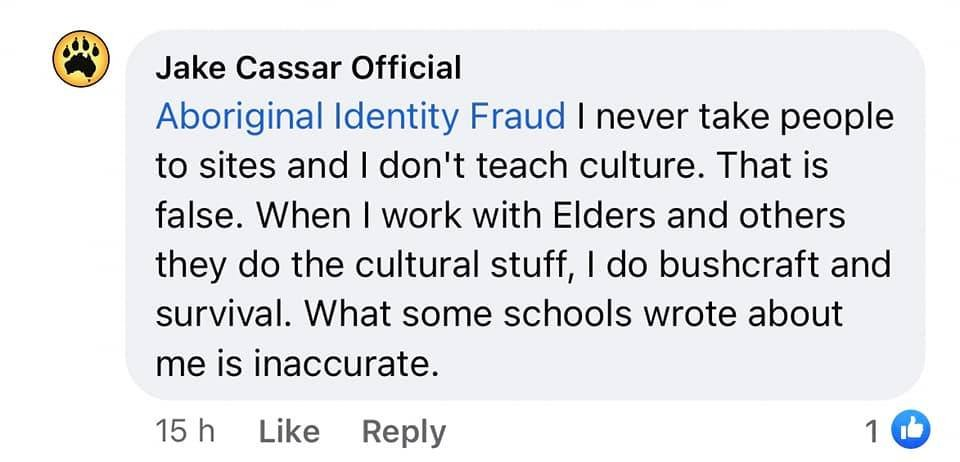

Pseudoarchaeology

The Save Kariong Sacred Lands campaign is a primary theatre for this settler simulation. The campaign centers on the protection of the “Grandmother Tree” and the “Kariong Hieroglyphs” (Gosford Glyphs).

● The Grandmother Tree:

This specific Angophora tree has been mythologized by the campaign as a spiritual totem. In the context of The Cave, this tree parallels the Baah-boraahk tree—a source of gnosis and authority that validates the settler’s

connection to place. The campaign elevates this single tree to delegitimize the broader land management rights of the DLALC, effectively using one “sacred” object to block Aboriginal economic self-determination.

● The Kariong Hieroglyphs:

The campaign frequently references the “Gosford Glyphs,” a set of carvings widely debunked by archaeologists as a modern hoax but promoted by Cassar and the GuriNgai group as evidence of ancient Egyptian contact. This directly mirrors the “Timeline” in The Cave, which posits “ancient aliens” and “Egyptian-style engravings” as the true history of the land.

By promoting this pseudoarchaeology, the campaign attempts to displace Aboriginal history with a “global” heritage that white settlers can claim ownership of, thereby erasing the specific sovereignty of Aboriginal people.

9.3 Save Kincumber Wetlands: The Phantom Protest

The Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign exemplifies the weaponization of misinformation. In 2025, the CEA and its allies launched a protest movement against a “proposed

development” at Kincumber. However, investigations revealed that no development application had been submitted, no environmental risk verified, and no sacred sites declared endangered by qualified Aboriginal authorities.

This “Phantom Protest” serves the “Sleeper Agent” doctrine of The Cave by:

Simulation: Creating a simulacrum of a crisis to validate the existence of the “protectors.” If there is no threat, the “warrior” has no purpose; therefore, threats must

be manufactured.

Mobilizing the Base: Keeping the “troops” active and angry, reinforcing the narrative of constant threat (“The Reckoning”).

Pre-emptive Strike: Delegitimizing the DLALC before they can even propose a project, effectively freezing their assets through reputational warfare.

9.4 The Campfire Collective and the GuriNgai Fraud

The Campfire Collective operates as the “cultural and emotional amplification arm” of Cassar’s network.

It gathers people in intimate settings to share stories, music, and “secret knowledge,” replicating the “Tea” ceremonies of The Cave.

● Emotional Recruitment: These events foster a “cultic emotional community” where the bounds of reality are softened, making participants more receptive to the conspiratorial and pseudo-spiritual narratives of the group.

● GuriNgai Validation: The Collective frequently platforms speakers from the GuriNgai identity movement—a group of non-Aboriginal people claiming Aboriginal ancestry (specifically descent from Bungaree) to assert custodianship over the region. The Cave validates this fraud by incorrectly using the term “Guringai” and constructing a narrative where “spiritual connection” (which the GuriNgai claim) trumps genealogical or legal recognition. The “GuriNgai” provide the “Indigenous face” for the CEA’s anti-Land Council campaigns, acting as the “Bill and Dorothy” characters from the book—the “good” ones who align with the settler’s agenda.

9.5 Lisa Bellamy and the “Soft Entry” Gateway

Lisa Bellamy, a key figure in the CEA and Campfire Collective, exemplifies the role of the “enabler” or “soft entry” facilitator. She creates a bridge between mainstream community concerns (environment, overdevelopment) and the radical core of Cassar’s ideology. Her involvement in political campaigns (running as an independent) mirrors the protagonist’s

infiltration strategy in The Cave. She and other women in the movement (e.g., Sarah Blakeway, Sue Chidgey, Vicki Burke) operationalize the “Maternal Guardian” archetype, framing their obstruction of Aboriginal housing as a “mother’s protection” of the earth, thereby softening the eco-fascist edges of the ideology for a broader audience.

Sovereign Citizen Convergence and Future Risks

The ideology of The Cave does not exist in a vacuum; it aligns seamlessly with the broader “Freedom Movement” and sovereign citizen subcultures in Australia.

● Shared Epistemology: The distrust of “the system” (government, medicine, media) found in The Cave (“termites,” “Son of Sephraan”) is identical to the anti-state rhetoric of sovereign citizens.

● My Place and Freedom Summits: Cassar’s participation in events like the “MySelf Reliance Freedom Summit” and his association with “My Place” groups (which merge community gardening with anti-government conspiracy) demonstrates the cross-pollination of these networks.

● Escalation Risk: The “Reckoning” narrative in The Cave glorifies violent collapse and “culling.” As these groups become more insular and radicalized, the risk of “stochastic terrorism”—violence inspired by the rhetoric but not directly ordered—increases. The text provides a theological permission structure for such violence against “termites” (political enemies, Aboriginal land owners).

Conclusion

The Cave is a masterclass in myth-making for the purpose of radicalization. It creates a closed loop of logic in which:

The World is Dying (Eco-crisis).

Humans are the Cause (Misanthropy).

The Yowies are the Solution (Eco-Fascism).

Jake Cassar is the Messenger (Charismatic Authority).

Violence is the Method (Radicalization).

The text synthesizes the alienation of modern men, the aesthetics of environmentalism, and the structural paranoia of conspiracy theories into a potent viral ideology. It is not merely a story about a man trapped in a cave; it is a lure designed to trap the reader in “The Cave” of the group’s worldview—a dark, claustrophobic reality where the only way out is through the destruction of the self and the consumption of the world.

The Cave stands as a warning document, illustrating how the noble desire to protect the environment can be hijacked and radicalized into a justification for totalitarian control and inhumanity. It is the scripture of a “cult of settler sovereignty” that seeks to erase Indigenous

people not with guns, but with myths. The integration of this narrative into the operational strategies of the CEA, Campfire Collective, and GuriNgai movement represents a significant and evolving threat to Aboriginal sovereignty and social cohesion in the Central Coast region.

The Cave by Jake Cassar really has to be seen to be believed; just not in the way Mr Cassar clearly intended.

Leave a comment