Abstract

This article further examines the psychological, sociological, and cultural literature on cult disengagement and recovery, applying these frameworks to the GuriNgai group and the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA). Drawing on foundational work by Langone, Lalich, Lifton, Singer, and Hassan; including Langone’s analysis of cultic trauma and Hassan’s BITE model of behavioural, informational, thought, and emotional control, it explores the coercive strategies used by high-control groups to recruit and retain members.

We argue that the GuriNgai and CEA networks operate as settler cults, relying on identity fraud, charismatic leadership, and spiritual manipulation, often infused with conspiratorial populism and QAnon-adjacent rhetoric, to create tightly bounded ideological systems.

These dynamics produce a wide spectrum of harms. Individuals who begin to question their place in the group often experience cultural disorientation and emotional trauma.

Fractured kinship ties may isolate members from family and cultural roots. Youth may be taught to disregard Elders, fostering intergenerational mistrust.

At a broader level, communities may become divided and confused over rightful cultural leadership and governance, contributing to the erosion of legitimate Aboriginal authority and cultural continuity.

Further tangible harms include depression, anxiety, feelings of cultural betrayal, disrupted education trajectories, severed family and community relationships, financial hardship, and loss of employment due to ideological isolation.

These impacts are compounded by the silencing of Aboriginal voices within key public and institutional forums, exacerbating the marginalisation of authentic cultural custodianship.

By embedding these settler-colonial narratives within pseudo-spiritual rhetoric, the groups obscure their lack of legitimacy while inflicting lasting psychological, interpersonal, and socio-political harm.

Nevertheless, recovery is possible through critical education, trauma-informed care, and culturally safe reintegration, offering pathways for healing grounded in truth-telling and ethical accountability.

This analysis situates the GuriNgai and CEA within the broader settler-colonial framework, illustrating how cultic dynamics operate as a form of neocolonial control, perpetuating historical patterns of Indigenous displacement and cultural appropriation.

1. Introduction: Contextualizing Settler Cults and Neocolonial Violence

This report examines the GuriNgai group and the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), two high-control organizations operating in Australia.

These entities are characterized by their reliance on Indigenous Identity appropriation and fraud, charismatic leadership, and spiritual manipulation, which collectively contribute to the formation of tightly bounded ideological systems.

The activities of these groups inflict a wide spectrum of harms to the participants, ranging from individual psychological trauma and cultural disorientation to the broader erosion of legitimate Aboriginal authority and cultural continuity.

Situating these groups within the larger framework of settler-colonialism, we demonstrate how their cultic dynamics function as a contemporary form of neocolonial control, perpetuating historical patterns of Indigenous displacement and cultural appropriation.

Our central argument is that the GuriNgai and CEA networks exemplify “settler cults.” This designation isn’t merely a descriptive label but serves as a critical analytical lens.

It highlights that these groups are not isolated phenomena, but are deeply embedded within, and actively perpetuate, the historical power dynamics of settler-colonialism in Australia.

This perspective extends beyond a general analysis of mind control, focusing on how such control serves a colonial agenda by usurping Indigenous identity and authority.

Through their operations, these groups leverage psychological and sociological control mechanisms, particularly identity fraud and spiritual manipulation, as a contemporary form of neocolonial violence.

This perpetuates historical patterns of Indigenous displacement and cultural appropriation, inflicting profound individual, interpersonal, and socio-political harms.

Nevertheless, the report underscores that recovery from such involvement is possible through critical education, trauma-informed care, and culturally safe reintegration, all grounded in truth-telling and ethical accountability.

We delve into the theoretical underpinnings of cultic control, analyze its specific manifestations within the GuriNgai and CEA, detail the multifaceted harms incurred, explore the complex processes of exit and recovery, and propose institutional and community-level interventions aimed at fostering accountability and healing within the Australian Indigenous context.

2. Defining Cults: Formal Criteria and Theoretical Foundations

To establish that the GuriNgai and CEA operate as cultic organisations, it’s essential to engage critically with multidisciplinary definitions of cults. High-control groups, often termed cults, employ sophisticated psychological and sociological mechanisms to exert influence over their members.

Understanding these foundational theories is crucial for comprehending the dynamics at play within groups like the GuriNgai and the Coast Environmental Alliance.

Michael Langone (1993) defines a cult as “a group or movement exhibiting great or excessive devotion to some person, idea, or thing, and employing unethical manipulative techniques of persuasion and control… to advance the goals of the group’s leaders, to the actual or possible detriment of members, their families, or the community” (Langone, 1993, p. 5).

This definition underscores the exploitative structure of groups that use manipulation and devotion to consolidate power (Langone, 1993).

Robert Jay Lifton’s (1989) framework of “ideological totalism” outlines eight key themes of cultic control: milieu control, mystical manipulation, demand for purity, cult of confession, sacred science, loading the language, doctrine over person, and dispensing of existence (Lifton, 1989).

These elements describe how cults engineer cognitive isolation and total commitment through a comprehensive system of belief, language, and behaviour (Lifton, 1989).

Janja Lalich (2004) builds on this with the concept of “bounded choice,” where cult members surrender personal agency through mechanisms of dependency, coercion, and ideological closure (Lalich, 2004).

Her notion of a “self-sealing system” captures how criticism and doubt are neutralised internally, preventing escape or critical reflection (Lalich, 2004).

A significant aspect of this bounded reality is the “illusion of freedom” presented by cults (Lalich, 2004). This is a sophisticated recruitment strategy that co-opts universal human desires for self-actualization and belonging (Lalich, 2004).

Cults initially present themselves as havens of individual freedom and enlightenment, offering sanctuary from societal constraints and a platform for personal growth (Lalich, 2004).

This appeal explains why occasionally intelligent, educated, and reasonable individuals can be drawn into these groups, as they seek to apply their intellect and abilities towards seemingly altruistic goals (Lalich, 2004).

This highlights that cults exploit positive human aspirations, not solely pre-existing vulnerabilities (Lalich, 2004).

The internalization of this bounded choice means that recovery must address not just external control, but the deeply ingrained cognitive and emotional frameworks that perpetuate self-limitation and dependency (Lalich, 2004).

This necessitates a profound re-education of self-perception and decision-making processes, helping individuals to relearn critical thinking and trust their own judgment, which was systematically eroded within the cultic environment (Lalich, 2004).

Steven Hassan (2015) contributes the BITE model: Behaviour, Information, Thought, and Emotional control, as a practical diagnostic tool to identify authoritarian cults (Hassan, 2015).

“BITE” categorizes the specific methods cults use to recruit and maintain influence over individuals (Hassan, 2015).

The GuriNgai and CEA exhibit numerous characteristics consistent with this model, displaying several red flags:

Behavior Control: These groups regulate members’ physical reality, dictating living arrangements, controlling types of clothing, and influencing diet and sleep. Financial exploitation and dependence are common, and members often spend major time in group indoctrination, requiring permission for significant decisions. Individualism is discouraged in favor of groupthink, with rigid rules and the instillation of dependency (Hassan, 2015).

For instance, members may be pressured to cut ties with questioning family members or discouraged from attending community events outside the group’s control.

Observable behaviors include controlling language in social media posts, such as coded references to ‘awakened’ versus ‘asleep’ individuals, and emotional surveillance during workshops.

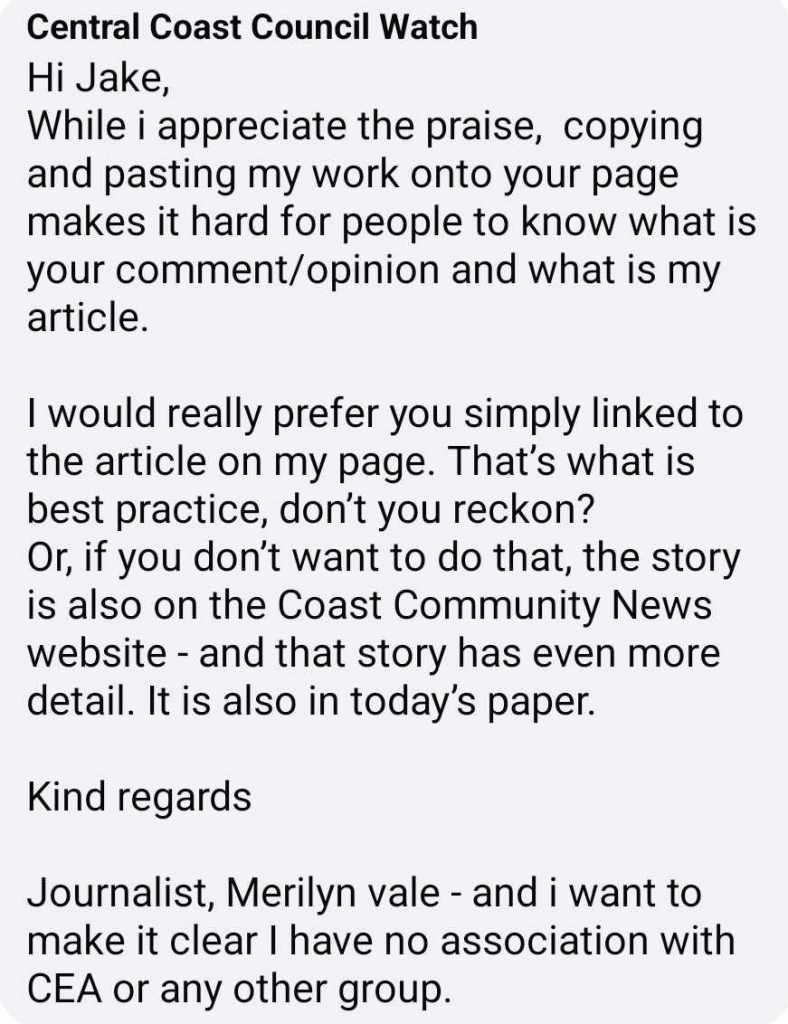

Information Control: Cults deliberately withhold or distort information, systematically lying to members and minimizing access to non-cult sources.

Information is compartmentalized into insider/outsider narratives, and spying on other members may be encouraged.

Extensive use of cult-generated information and unethical use of confession are also common (Hassan, 2015).

Members may be warned not to engage with journalists or instructed to dismiss respected Aboriginal Elders as spiritually corrupt.

Thought Control: Groups require members to internalize the group’s doctrine, sometimes even changing a person’s name and identity.

Loaded language and clichés are used to constrict thought, and only “good and proper” thoughts are encouraged.

Hypnotic techniques may be used to alter mental states, and memories can be manipulated.

Thought-stopping techniques are taught to prevent critical inquiry, and rational analysis is rejected.

Questioning the leader or doctrine is forbidden, and alternative belief systems are labeled as illegitimate, instilling a new “map of reality” (Hassan, 2015).

Questioning leadership decisions may be framed as betrayal of sacred responsibility to ‘Country’.

Emotional Control: Cults manipulate and narrow the range of feelings, teaching emotion-stopping techniques. They promote feelings of guilt or unworthiness, often through identity, social, or historical guilt, making individuals feel that problems are always their own fault, never the leader’s or the group’s (Hassan, 2015).

Fear is instilled, including fear of thinking independently, the outside world, enemies, or losing salvation or being shunned (Hassan, 2015). This fosters emotional dependency and a constant state of moral tension.

The BITE model, beyond being a diagnostic tool, implicitly highlights the gradual, systematic erosion of autonomy and self-identity within cults (Hassan, 2015).

The detailed list of control mechanisms, such as changing a person’s name and identity, manipulating memory, and instilling a new “map of reality” (Hassan, 2015), demonstrates a process of de-individuation where the individual’s original self is replaced by a group-defined identity (Hassan, 2015).

The utility of the BITE model in recovery suggests that re-establishing critical thinking and actively acknowledging suppressed negative experiences is paramount (Hassan, 2015).

This implies that cult-induced trauma involves profound cognitive distortions and emotional suppression that must be systematically dismantled during the healing process (Hassan, 2015).

If the brain tends to suppress negative information about traumatic situations (Hassan, 2015), then recovery isn’t a passive process but requires active, guided re-engagement with suppressed truths and the development of critical faculties that were deliberately undermined by the cult’s thought-stopping techniques (Hassan, 2015).

Margaret Singer (2003) focuses on thought reform, emphasizing techniques such as love bombing, phobia indoctrination, and induced dissociation (Singer, 2003).

These methods are used to destabilize identity and reframe members’ relationships with truth and selfhood (Singer, 2003).

Additional definitions from Richardson (1993), Anthony and Robbins (1992), and Zablocki (2001) introduce a sociological perspective (Richardson, 1993; Zablocki, 2001).

They emphasize the dynamics of control through social structure, charismatic authority, role insulation, and the social construction of truth and belonging (Richardson, 1993; Zablocki, 2001).

Zablocki, in particular, describes cults as groups employing “charismatic authority and strategic social encapsulation” to enforce ideological commitment and isolate followers from competing worldviews (Zablocki, 2001).

Together, these frameworks outline the necessary criteria for identifying cultic groups: (1) charismatic leadership and centralized authority, (2) unethical persuasion and manipulation, (3) enforced conformity and epistemic insulation, and (4) harm to members, critics, and the wider society (Richardson, 1993; Zablocki, 2001).

As subsequent sections demonstrate, the GuriNgai and CEA not only meet but exemplify these characteristics in structure, practice, and impact.

The Cultic Lifecycle: From Idealization to Psychological Entrapment

Grant’s (2022) Cultic Lifecycle framework articulates a progression that begins with idealistic promise and culminates in psychological entrapment (Grant, 2022).

This model reveals how individuals are drawn into cults during stressful life transitions, where cults exploit vulnerabilities and inherent human desires for meaning and self-improvement (Grant, 2022).

Cults effectively fulfill Maslow’s higher-level needs, such as a sense of community (32.4% of participants), self-understanding (29.7%), and purpose/spirituality (27.0%) (Grant, 2022).

This explains their powerful draw, particularly for individuals experiencing anomie-related or interpersonal stressors, highlighting cults as substitute social structures that provide a distorted sense of belonging and meaning, making them appealing even to “psychologically healthy people” (Grant, 2022).

The trajectory typically follows four key stages:

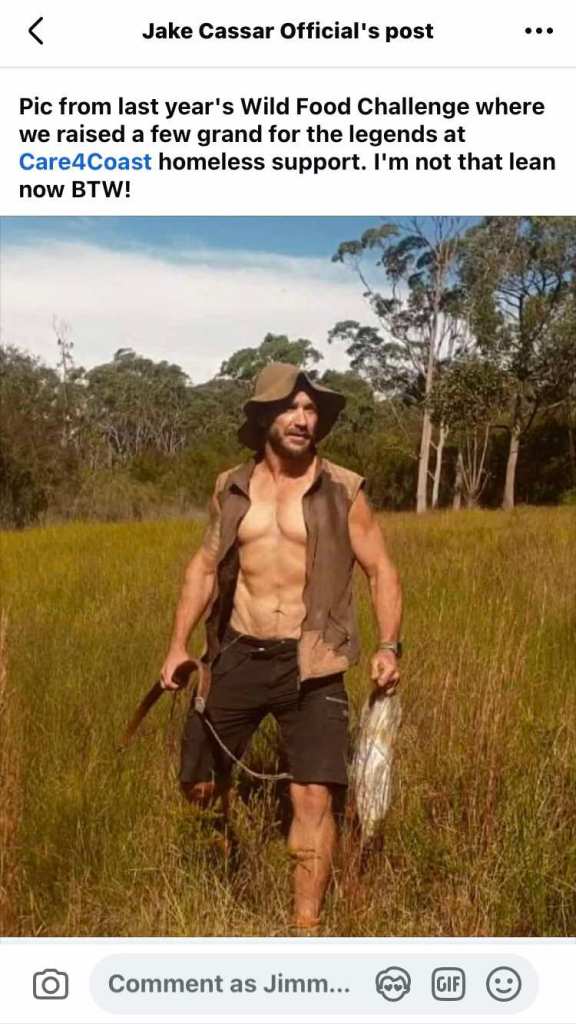

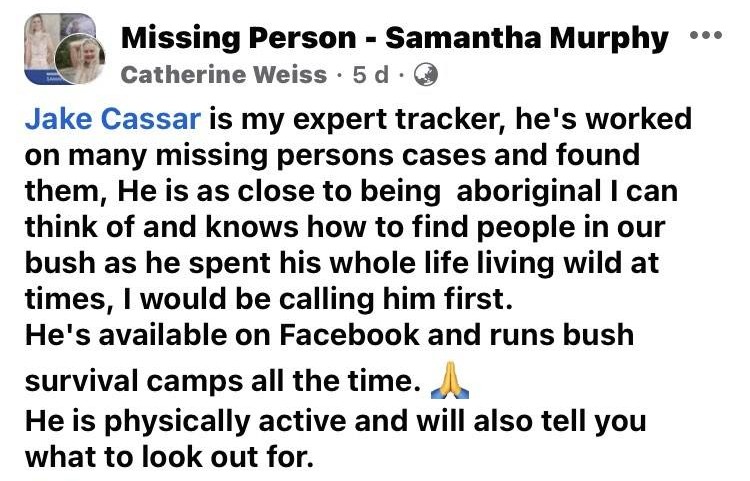

Idealization: For the GuriNgai group, this process starts with the appropriation of Aboriginal motifs, spiritual language, and activist rhetoric, constructing a surrogate cultural identity for individuals lacking recognized community ties. In the case of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), the lifecycle begins with a compelling narrative of ecological defense, casting Jake Cassar as a spiritual bulwark against environmental destruction and a charismatic ecological protector.

These foundational narratives serve as potent recruitment mechanisms by fulfilling unmet needs for belonging, identity, and existential purpose.

Consolidation of Control: As control is consolidated, members are expected to adopt group-specific behaviors and cut ties with dissenting voices. The “cult of confession” and “demand for purity” (Lifton, 1989; Singer, 2003) within this phase create a system of perpetual guilt and self-blame, where any internal doubt or external problem is attributed to the member’s “impurity” rather than the group’s flaws (Lifton, 1989; Singer, 2003).

This mechanism reinforces leader authority and prevents dissent, making exit extremely difficult due to instilled fears of spiritual punishment or ostracism (Grant, 2022).

Isolation: During this phase, emotional and intellectual confinement deepens, often manifesting in distrust toward Elders, avoidance of critical media, and increased social withdrawal.

Former members report being pressured to cut ties with questioning family members, discouraged from attending community events outside the group’s control, and shamed for engaging with culturally legitimate Aboriginal organizations.

Psychological Harm: This culminates in psychological harm, where fear, shame, and guilt replace the initial sense of purpose. Some ex-members report feeling spiritually contaminated or disoriented after leaving the group, reflecting the deep psychological imprint of prolonged cultic control.

Charismatic Leadership and Spiritual Fraud

At the core of all high-control cultic formations lies charismatic authority (Richardson, 1993). Max Weber’s (1947) theory of charisma describes the “exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character” attributed to leaders whose claims aren’t grounded in traditional or legal-rational legitimacy, but in personal mythos and emotional appeal (Richardson, 1993).

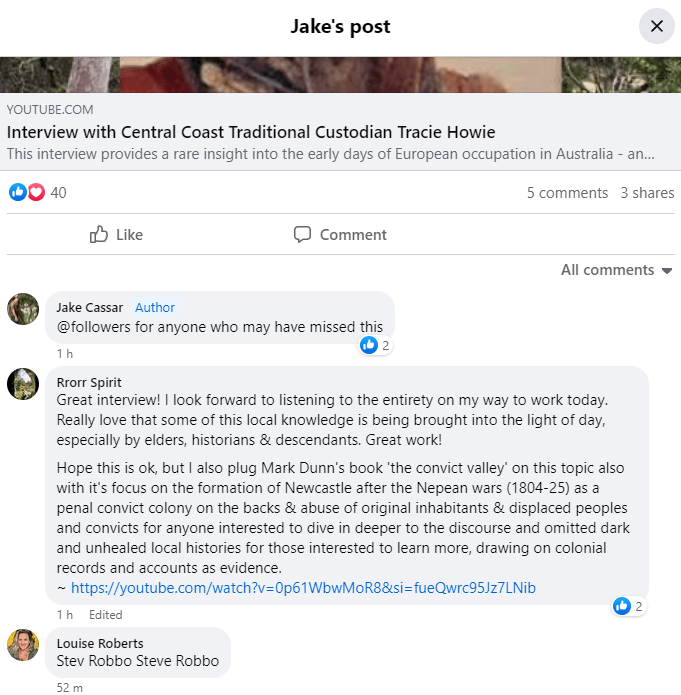

Both the GuriNgai and Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) are organized around such centralized charismatic figures, Tracey Howie and Jake Cassar, whose unverified or demonstrably false claims to expertise, spiritual, or cultural knowledge become the primary source of institutional authority within their respective groups (Cooke, 2025d).

Tracey Howie self-identifies as an Aboriginal Elder, cultural educator, and law-woman, asserting descent from the so-called “Guringai,” “Wannangine,” and “Walkaloa” clans (Cooke, 2025d).

These clans have no documented historical basis in anthropological or community-endorsed sources (Cooke, 2025d; Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

Howie’s identity claims and associated cultural authority have been systematically challenged by Aboriginal community members, historians, and genealogical researchers (Cooke, 2025d; Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

Nevertheless, she maintains public influence through institutional partnerships, educational workshops, and media visibility, leveraging her position to delegitimize genuine Aboriginal authority structures such as the Metropolitan and Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Councils (Cooke, 2025d; Hornsby Shire Council, 2020; Wyong Coal, 2015).

Her charismatic influence operates in classic cultic fashion: elevating personal narrative above community verification, dispensing with objective genealogical critique, and centering herself as the sole interpreter of “truth” and “law” in local Indigenous affairs (Cooke, 2025d).

Jake Cassar similarly exercises charismatic dominance, albeit through a spiritualized faux-environmental lens (Cooke, 2025d; Cooke, 2025e).

Presenting himself as a bushcraft expert, conservationist, and protector (Jake Cassar Bushcraft, n.d.; Permaculture Northern Beaches, 2016; Pretty Beach House, n.d.), Cassar uses his persona to attract a broad social media following and mobilize campaigns exclusively opposing Aboriginal-led developments (Cooke, 2025d).

He routinely incorporates spiritual language, mythopoetic storytelling, and references to “sacred trees,” “ancient wisdom,” and being “custodians” in describing the lands he claims to defend (Cooke, 2025d).

Yet his campaigns have repeatedly targeted Aboriginal-owned lands and been based on fabricated mythologies, such as the debunked “Kariong Hieroglyphs” or the spiritually charged but culturally unauthenticated “Grandmother Tree” (Cooke, 2025d).

His leadership mirrors Lifton’s (1989) concept of “mystical manipulation,” wherein leaders manufacture spiritual authority by aligning themselves with supposedly divine or cosmic purpose—thereby rendering dissent not merely wrong but sacrilegious (Lifton, 1989).

Both leaders exercise unilateral interpretive power. Their personal narratives function as sacred science (Lifton, 1989), immune to scrutiny, and their declarations about ancestry, land, and law are treated as inviolable truths within their organizations (Lifton, 1989).

Dissent is preemptively neutralized by framing it as racism, cultural ignorance, or government corruption (Cooke, 2025d).

This epistemic closure is indicative of what Lalich (2004) terms a “bounded choice” environment: followers are presented with only one acceptable interpretive framework, that of the leader, under the guise of cultural or ecological authenticity (Lalich, 2004).

From the perspective of the BITE model (Hassan, 2015), Howie and Cassar enforce Behavioural control (through attendance at rituals, land visits, and protests), Information control (through misinformation about Aboriginal history and land rights), Thought control (by redefining settler guilt as spiritual ancestry or custodianship), and Emotional control (through guilt induction and fear of exclusion) (Hassan, 2015).

They perform what Tobias and Lalich (1994) describe as “pseudo-tribal” leadership, fostering a closed in-group identity in which traditional relational accountability is replaced with authoritarian loyalty to the central figure (Richardson, 1993).

Importantly, these dynamics aren’t merely internal. Cassar and Howie’s charisma is projected outward to institutions and public audiences.

Local councils, schools, and environmental organizations often collaborate with or platform these individuals, unaware of the fabricated bases of their authority or the coercive nature of their group structures (Cooke, 2025d).

Their ability to manipulate institutional relationships underscores Richardson’s (1993) emphasis on how cults strategically manage public legitimacy while maintaining authoritarian control internally (Richardson, 1993).

The cultic pattern of centralized spiritual fraud within both the GuriNgai and CEA reflects what Johnson (1967) called the “substitutive ideology” of charismatic movements: the replacement of inherited or verified traditions with fabricated systems designed to reinforce leader control (Richardson, 1993).

This not only perpetuates harm within their respective groups but also contributes to the epistemic erasure of legitimate Aboriginal law, heritage, and governance (Cooke, 2025d).

Table 1: Application of Hassan’s BITE Model to GuriNgai and CEA

BITE Model Component

General Cultic Manifestations (Hassan, 2015)

Specific Manifestations in GuriNgai/CEA (Cooke, 2025d; Hassan, 2015)

Behavior Control

Regulate physical reality, dictate living arrangements, financial exploitation, restrict leisure, require permission for major decisions, discourage individualism, impose rigid rules, instill dependency.

Members discouraged from speaking to questioning family; pressured to cut ties with culturally legitimate Aboriginal organizations; policing of group narratives during public meetings; emotional surveillance during workshops; control over social media language (e.g., ‘awakened’ vs. ‘asleep’).

Information Control

Deliberately withhold/distort information, systematically lie, minimize access to non-cult sources, compartmentalize information, encourage spying, extensive use of cult-generated information, unethical use of confession.

Members warned not to engage with journalists; instructed to dismiss respected Aboriginal Elders as spiritually corrupt or politically compromised; suppression of critical inquiry; self-sealing narratives that conflate charisma with Indigenous legitimacy.

Thought Control

Require internalization of group’s doctrine, change person’s name/identity, use loaded language/cliches, encourage only ‘good’ thoughts, manipulate memories, teach thought-stopping, reject critical thinking, forbid critical questions about leader/doctrine, label alternatives as illegitimate, instill new ‘map of reality’.

Questioning leadership decisions framed as betrayal of ‘sacred responsibility to Country’; enforced groupthink; use of jargon like ‘awakened’ vs. ‘asleep’ to regulate belief; fostering emotional dependency and moral tension.

Emotional Control

Manipulate/narrow range of feelings, teach emotion-stopping techniques, promote self-blame, instill guilt/unworthiness (identity, social, historical guilt), instill fear (independent thinking, outside world, enemies, losing salvation, leaving), extremes of emotional highs/lows (love bombing), ritualistic confession, phobia indoctrination.

Weaponization of guilt and spiritual shame; instilling fear of spiritual punishment or communal exclusion for voicing doubts; members afraid any independent thought could sever spiritual belonging; feelings of cultural betrayal and spiritual contamination post-exit.

3. The GuriNgai and Coast Environmental Alliance: Case Studies in Settler Cultism

The GuriNgai group and the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) serve as compelling case studies illustrating the mechanisms of settler cultism in contemporary Australia.

Their operations reveal how identity manipulation and pseudo-spiritual rhetoric are deployed as tools of neocolonial control.

Fabricated Identities and Cultural Appropriation: The GuriNgai Mythos

The GuriNgai group operates as a settler cult, fundamentally relying on identity fraud (Cooke, 2025d). This self-identified group is entirely composed of individuals with no known Aboriginal descent, community recognition, or cultural continuity (Cooke, 2025d).

They’ve established themselves across the Northern Beaches, Hornsby Shire, and Central Coast of New South Wales by misappropriating historical figures like Bungaree and his descendants, falsely asserting custodianship over Country to which they have no legitimate biological or cultural claim (Cooke, 2025d).

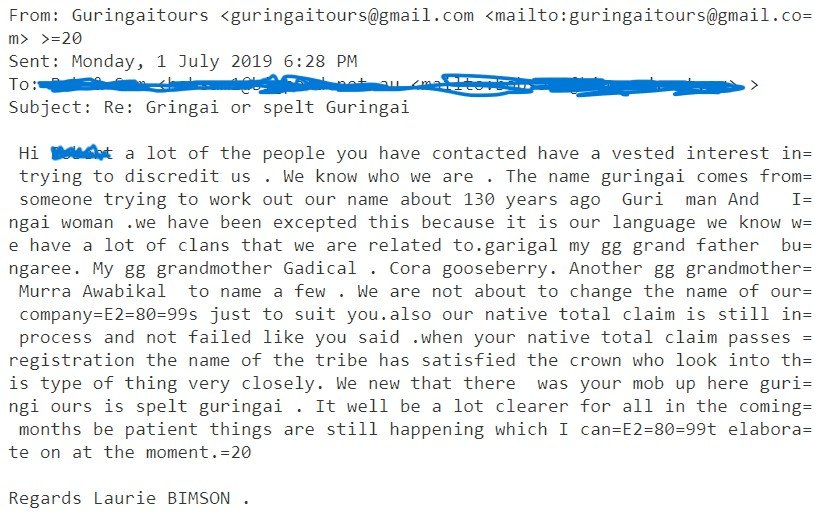

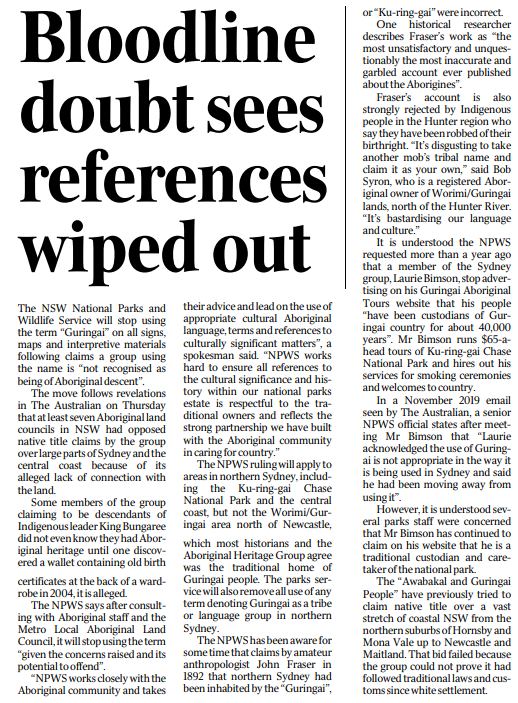

The term “GuriNgai” itself is a fabrication, first coined in 1892 by John Fraser based on a flawed analysis of Aboriginal languages (Cooke, 2025d; Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

There is no recorded evidence of its use prior to his publication (Kwok, 2015). Prominent ethnographers like Norman Tindale (1974) “scathingly criticized Fraser’s work” as “unquestionably the most inaccurate and garbled account ever published about the aborigines,” removing the term entirely from his influential maps (Kwok, 2015; Tindale, 1974).

Despite this, the modern GuriNgai group has deliberately rebranded and weaponized this fabricated colonial construct to facilitate illegitimate claims to land, culture, and authority (Cooke, 2025d).

The Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC) and six other Land Councils confirmed in a 2020 letter to the Premier of NSW that the GuriNgai claimants have no legitimate connection to Country in the Northern Beaches or Central Coast, and their 2013 Native Title claim was discontinued due to a complete lack of credible evidence for cultural continuity or descent (Metropolitan LALC, 2020; Cooke, 2025d).

The GuriNgai group’s use of this fabricated ethnonym and false claims to custodianship is not merely cultural appropriation but a deliberate act of neocolonial violence (Cooke, 2025d).

This reassertion of settler control through identity manipulation actively undermines Indigenous sovereignty and cultural continuity (Cooke, 2025d).

The persistence of the fabricated “Kuringgai/GuriNgai” ethnonym in public perception and institutional use (Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024), despite overwhelming academic and Indigenous refutation, illustrates the enduring power of colonial narratives over historical and cultural truth (Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

This structural issue makes it difficult for legitimate Aboriginal communities to assert their authority and for the public to discern authentic claims, as colonial inventions can become entrenched in the public consciousness, creating a “void” (Kwok, 2015) that fraudulent groups exploit.

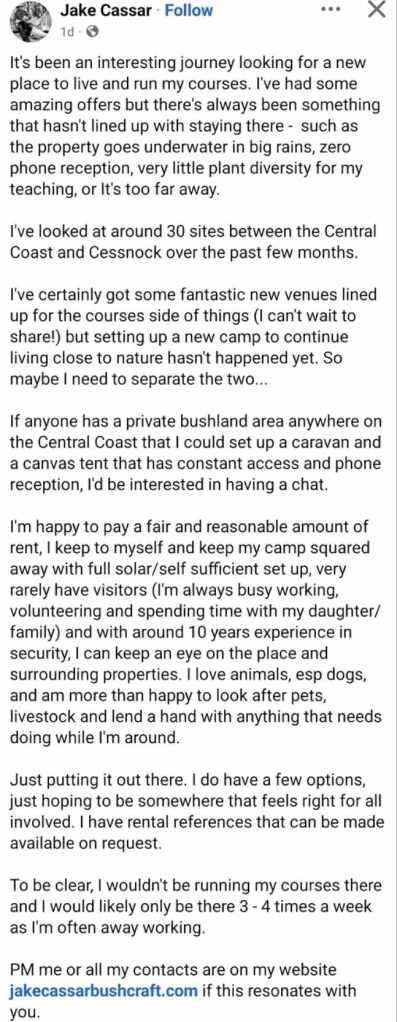

Jake Cassar and CEA: Entrepreneurial Spiritual Leadership and Faux-Environmentalism

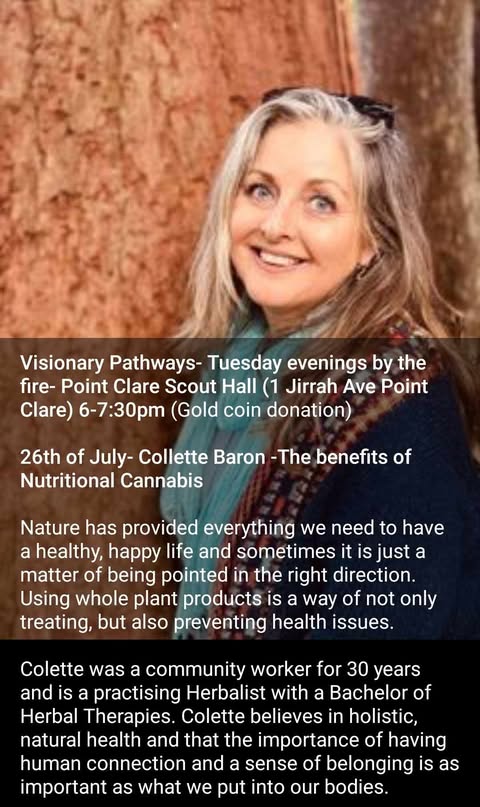

Jake Cassar, the founder of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and the public face of Jake Cassar Bushcraft, has cultivated a charismatic persona that aligns closely with the model of ‘entrepreneurial spiritual leadership’ (Coco, 2023).

His carefully crafted identity blends bush survivalism, apocalyptic prophecy, and spiritualized faux-environmentalism, reflecting a fusion of esoteric ecology and conspiratorial counter-modernity (Cooke, 2025e).

He positions himself as a “spiritual bulwark against environmental destruction” and a “charismatic ecological protector”.

Cassar is a self-taught bushcraft teacher, tour guide, and youth mentor (Jake Cassar Bushcraft, n.d.), presenting himself as a conservationist and reconciliation activist who claims to have learned from an Indigenous family (Permaculture Northern Beaches, 2016).

He offers tours on native plants and survival skills (Jake Cassar Bushcraft, n.d.) and has been credited for a Land and Environment Court ruling against development (Permaculture Northern Beaches, 2016).

He has also criticized others for not consulting Aboriginal people (Jake Cassar, 2019).

This self-presentation creates an aura of Indigenous legitimacy that masks his spiritual manipulation and faux-environmentalism (Cooke, 2025e). This strategic performance leverages public desire for reconciliation and environmental protection.

The irony of Cassar criticizing others for not consulting Aboriginal people (Jake Cassar, 2019) while being associated with a “settler cult” (Cooke, 2025d) highlights the manipulative nature of his claims. Cassar’s public persona is built on a mixture of charisma, bush knowledge, mystical intuition, and anti-institutional critique, traits that resonate strongly with the emotional and narrative forms of QAnon-adjacent movements (Cooke, 2025e).

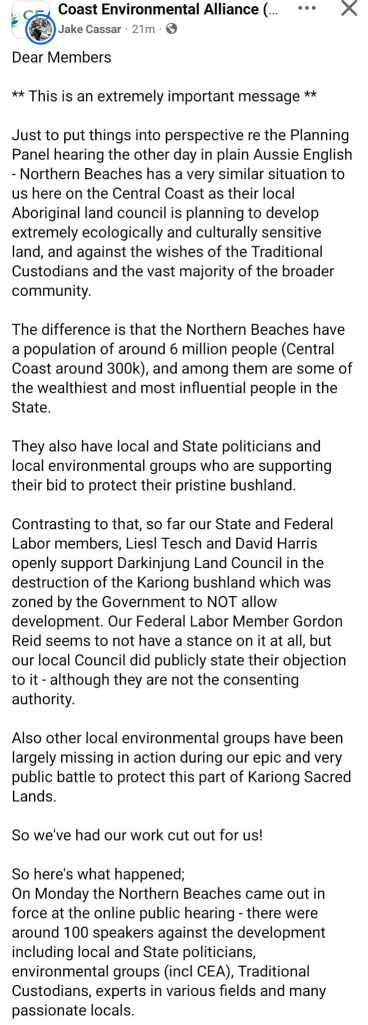

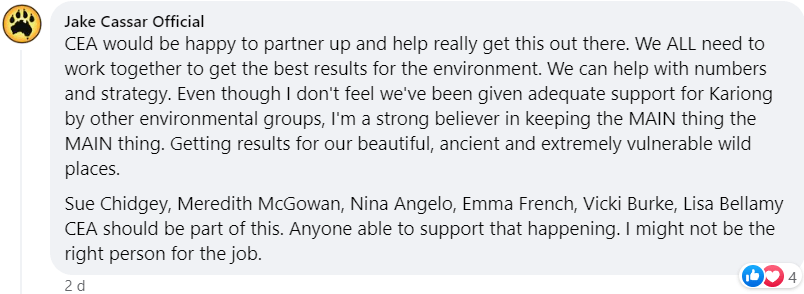

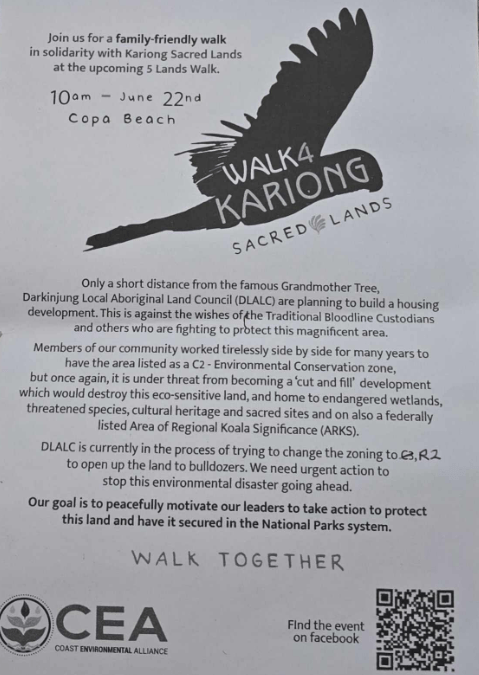

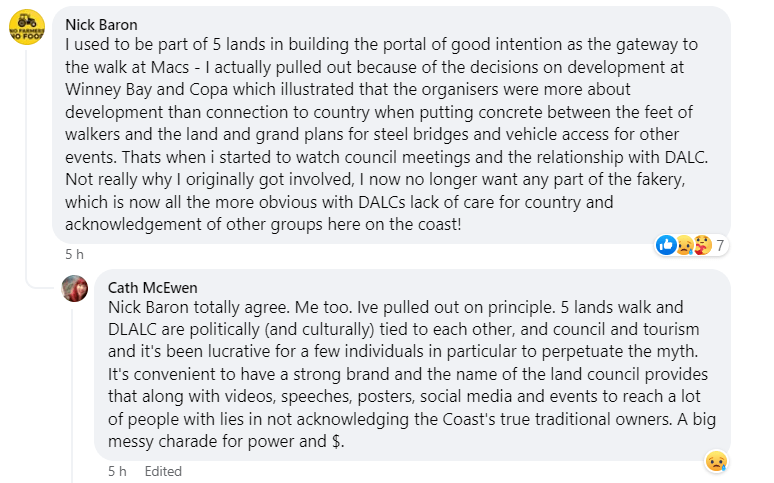

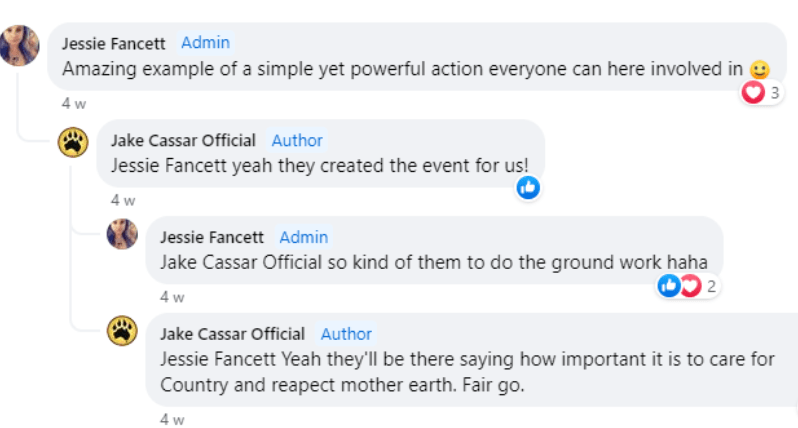

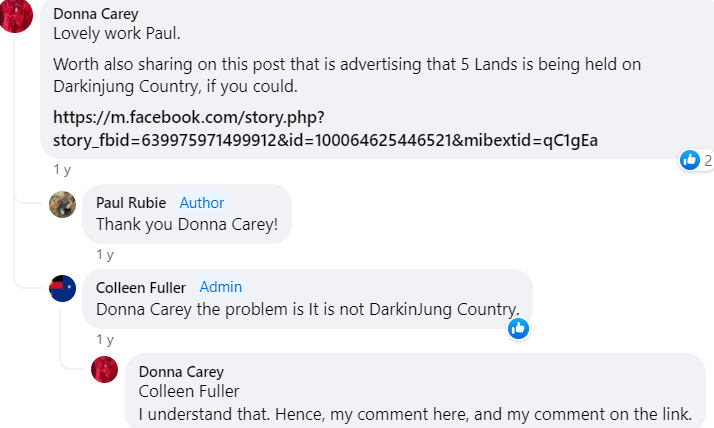

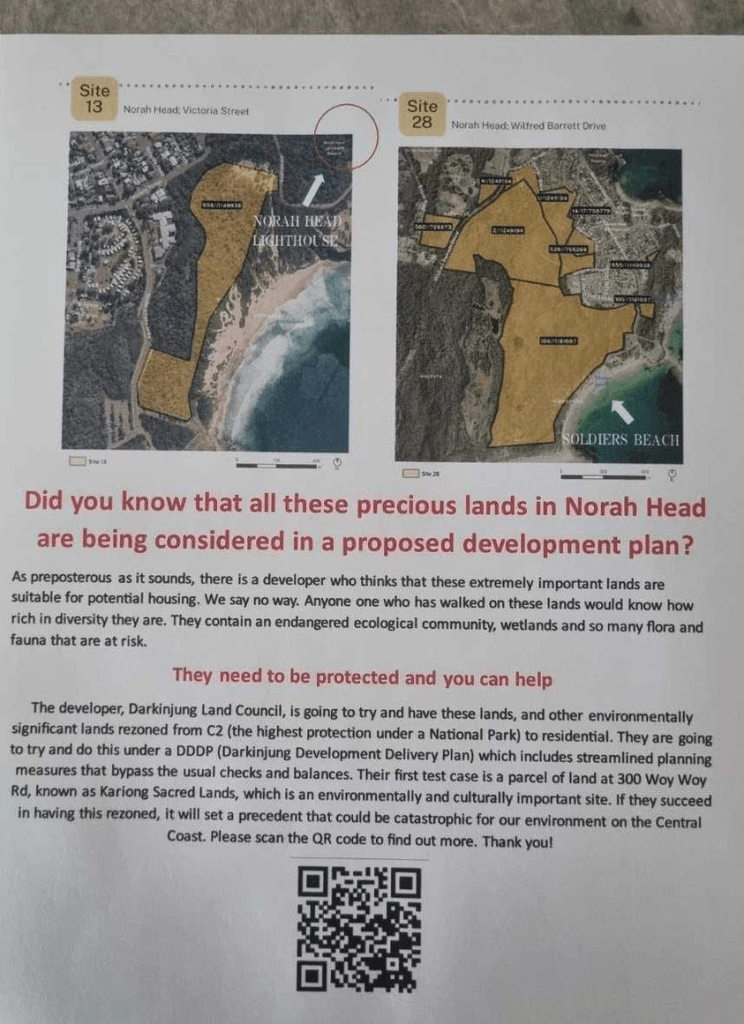

CEA began as a conservation-oriented alliance but quickly developed into a platform for activism against Aboriginal-led land developments, particularly those proposed by the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) (Cooke, 2025e).

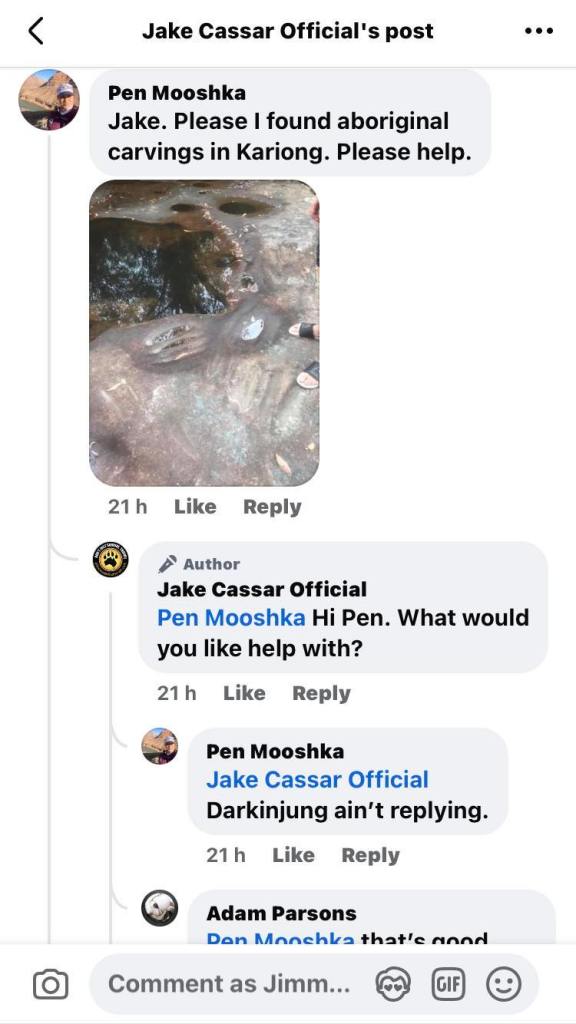

Cassar and CEA have led vocal campaigns against developments at Kariong, Kincumber, and the Northern Beaches, claiming the sites are ecologically fragile, culturally sacred, and spiritually significant (Cooke, 2025e).

Yet their activism is saturated with settler-conspiritual tropes: Cassar invokes ancestral spirits, earth energies, and “true custodianship,” often implying that non-Aboriginal people, himself included, possess superior spiritual knowledge and moral entitlement to land (Cooke, 2025e).

His rhetoric blends ecological crisis with spiritual warfare, asserting that unseen forces and ancient knowledge are under attack by corrupt institutions (Cooke, 2025e).

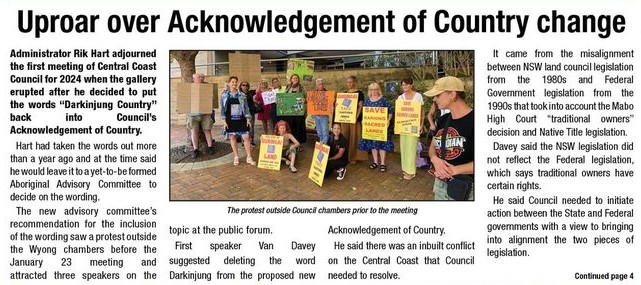

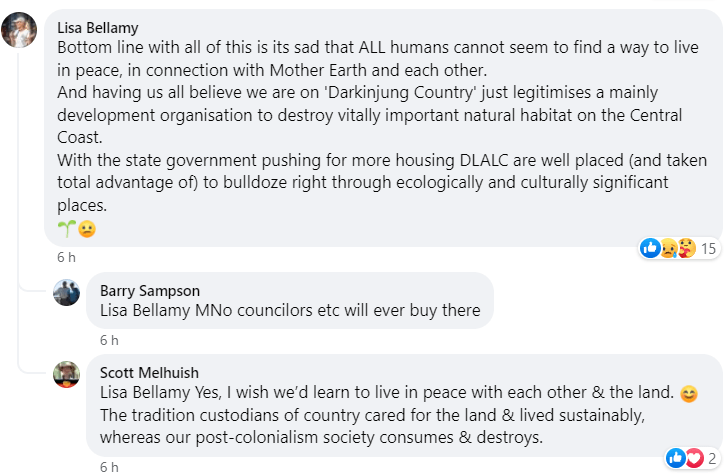

The conflict between CEA/GuriNgai and the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) over land development at Kariong (Coast Community News, 2020) further illustrates how pseudo-Indigenous groups weaponize environmental and cultural heritage concerns.

Cassar and Tracey Howie (GuriNgai) have opposed DLALC’s proposed housing development, citing the proximity to Kariong Sacred Lands and endangered flora and fauna (Coast Community News, 2020).

However, DLALC Chairperson Matthew West stated that independent investigations found no culturally significant sites on the specific land earmarked for development, and that buffer zones have been implemented where sites were identified (Coast Community News, 2020).

This dynamic creates internal division within the broader Indigenous community and confuses external stakeholders, as fraudulent claims are used to interfere with legitimate Indigenous governance and land management.

Mythmaking and Settler Fantasy

Cults don’t simply disseminate misinformation; they engineer alternative epistemologies (Richardson, 1993). One of the most insidious forms of this engineering is mythmaking, what Lincoln (1989) refers to as the fabrication of “authorizing narratives” that structure belief, identity, and belonging (Richardson, 1993).

Within the GuriNgai and CEA networks, mythmaking functions as a central technique of settler cultural production, blending pseudo-history, spiritualized fantasy, and visual spectacle to displace Aboriginal sovereignty and substitute fabricated traditions (Cooke, 2025d).

The GuriNgai group has manufactured a cosmology of fictitious clans, such as “Walkaloa” and “Wannangine,” as well as an invented language and mythology with no basis in the historical ethnographic or linguistic records of the Sydney or Central Coast regions (Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

These narratives are disseminated via ceremonies, land acknowledgements, and spiritual education programs which portray white individuals as descendants of Bungaree or “keepers” of the land’s energy (Cooke, 2025d).

This behavior reproduces what Deloria (1998) called “playing Indian,” wherein settler desires for rootedness and authenticity are projected onto fabricated Aboriginal identities (Deloria, 1998).

Similarly, CEA’s campaigns are structured around ecological mythologies that invert Aboriginal land rights into threats against sacred white relationships to Country (Cooke, 2025e). Jake Cassar’s mythologization of the “Grandmother Tree” and the Kariong Glyphs exemplifies what Barker (2022) describes as prepper-spiritual fusion narratives, where apocalyptic fears and spiritual destiny converge in the landscape (Barker, 2022).

Despite being debunked as modern graffiti (Coltheart, 2011), the Kariong Glyphs are portrayed by CEA as evidence of ancient truths concealed by governments and corrupt land councils (Cooke, 2025e). These myths aren’t marginal; they’re central to the group’s mobilization strategies (Cooke, 2025e).

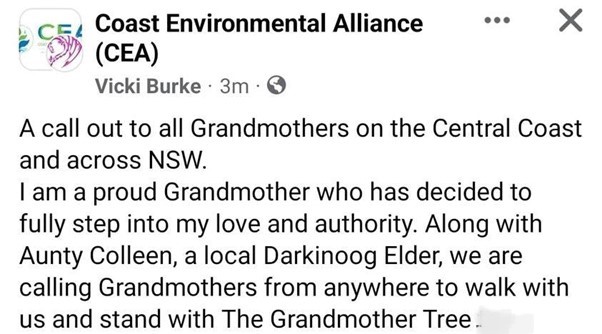

In the case of the “Grandmother Tree,” a single angophora outside the DLALC’s Kariong development footprint, has been sacralized through ritual performance, livestreamed veneration, and narrative repetition (Cooke, 2025e).

The tree, lacking Aboriginal cultural validation, becomes a cult object, infused with constructed meaning and defended as if sacred law (Cooke, 2025e).

This reflects what Comaroff and Comaroff (2009) identify as the commodification of indigeneity: a process where spiritual narratives are extracted from Aboriginal context and refashioned as symbolic capital for settler projects (Comaroff & Comaroff, 2009).

These mythologies allow for what Watego (2021) calls “fantasies of cultural benevolence.” Settler participants in the GuriNgai and CEA movements frame their roles not as appropriators but as spiritual custodians resisting modernity and corruption (Cooke, 2025d). The actual result, however, is the epistemic erasure of real Aboriginal law, culture, and genealogical authority (Cooke, 2025d). In line with Lifton’s “sacred science,” the myths are upheld with cultic rigidity, with any challenge treated as heresy (Lifton, 1989).

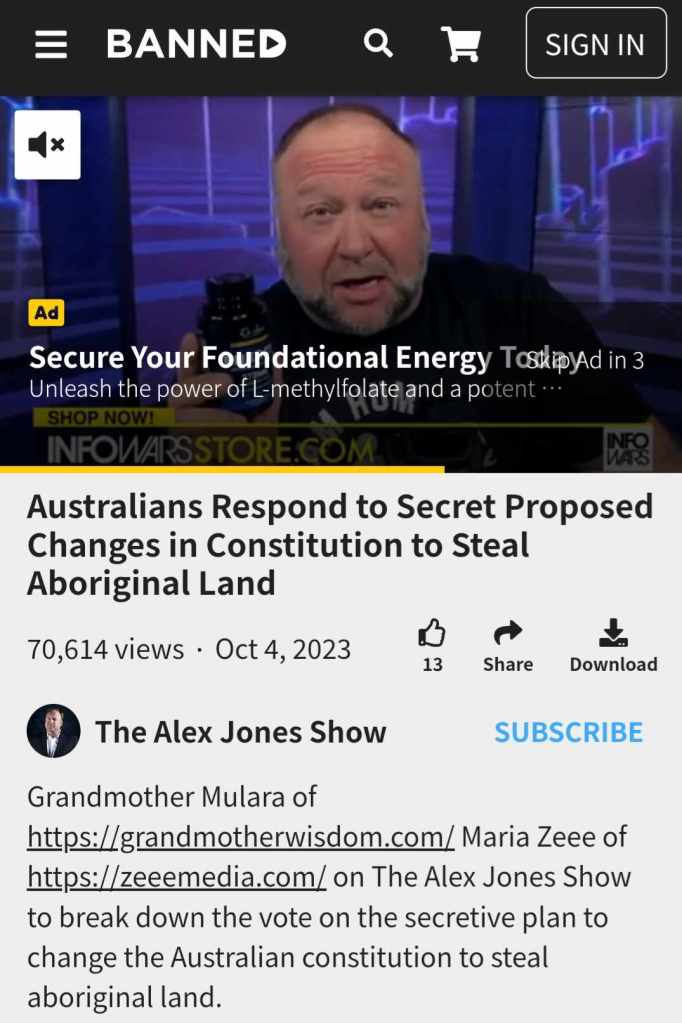

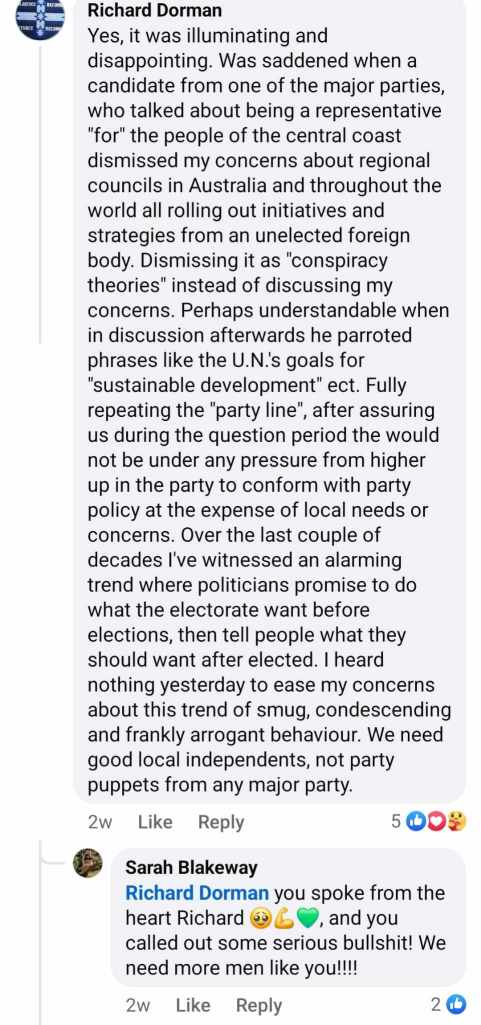

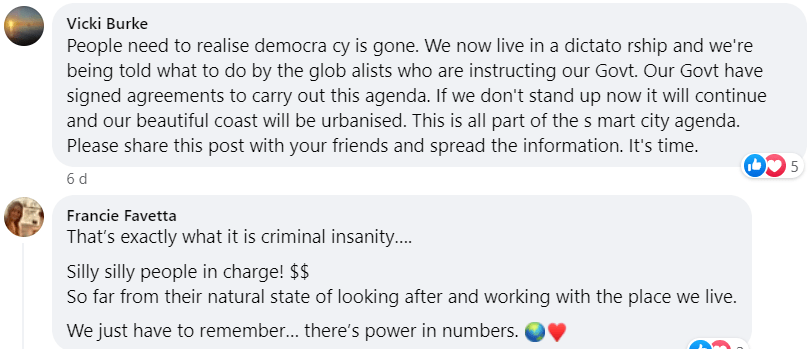

These dynamics are further sustained by conspiracist worldbuilding. The groups consistently claim that Aboriginal land councils are “government puppets,” that Aboriginal opposition is “cancel culture,” and that their own myths are “ancient knowledge” recovered through spiritual revelation (Cooke, 2025e). This closely mirrors the mechanisms of QAnon, as described by Montell (2021), wherein esoteric symbolism, spiritual warfare, and populist anti-institutionalism are fused into a totalizing belief system (Cooke, 2025e).

Within the GuriNgai–CEA alliance, this mythmaking serves dual cultic functions: internally, it binds followers to a sense of enchanted destiny; externally, it justifies political attacks on Aboriginal governance (Cooke, 2025d). The fantasy of ancient custodianship replaces legal recognition, ritual performance substitutes for kinship, and settler grief is reframed as Aboriginal belonging (Cooke, 2025d).

This settler spiritual fantasy is not merely appropriative; it is a deliberate tool of recolonization—one that enacts white possessiveness under the guise of sacred defense (Cooke, 2025d).

The Goolabeen Legacy: Conspiritual Mythmaking and the Recolonisation of Kariong

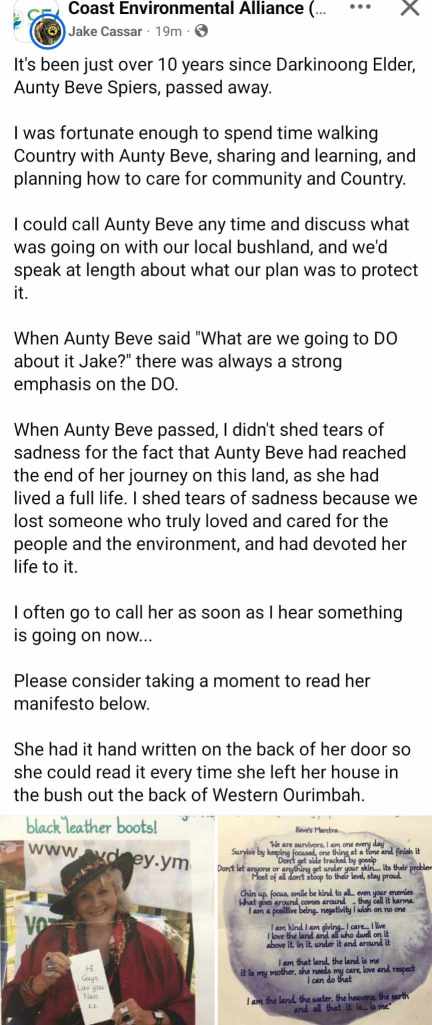

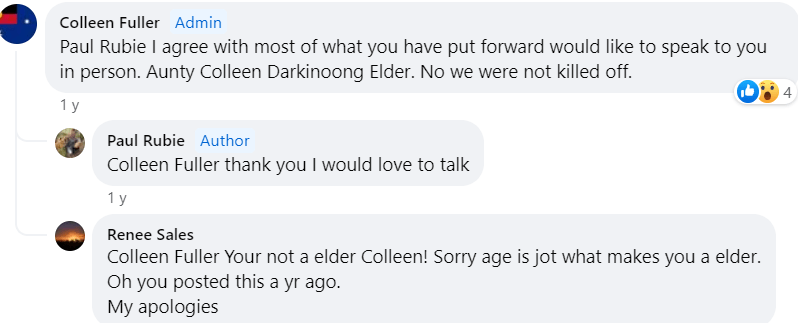

The mythological and conspiratorial foundations of CEA’s campaigns can’t be understood without reference to the legacy of Beverley “Beve” Spiers, also known as “Aunty Goolabeen” (Cooke, 2025f). Spiers, who falsely claimed to be a Darkinooong Elder, was central to the spiritual myth-making that redefined Kariong as a sacred site of Aboriginal–Egyptian contact and cosmic energy (Cooke, 2025f).

Her narratives, popularized from the late 1980s until her death in 2014, fused pseudoarcheology with fringe spirituality, asserting that Kariong’s so-called glyphs were evidence of interstellar communication and Dreaming portals (Cooke, 2025f). These claims were unverified by any credible Cultural, archaeological, genealogical, or linguistic evidence, yet they proved enormously generative in settler spiritualist circles (Cooke, 2025f).

Spiers’s death in 2014 didn’t mark the end of the fraudulent spiritual empire she constructed at Kariong. Rather, her legacy has metastasized, adopted and reframed by a new generation of settler activists and conspiracists who have fused spiritual appropriation, environmental posturing, and far-right ideology into a potent settler-colonial revival (Cooke, 2025f).

Through myth-making, ritual performance, and public disinformation campaigns, the followers of Goolabeen have not only endured but intensified, transforming Kariong into the epicenter of a broader project of recolonization cloaked in the language of sacred protection and Aboriginal allyship (Cooke, 2025f).

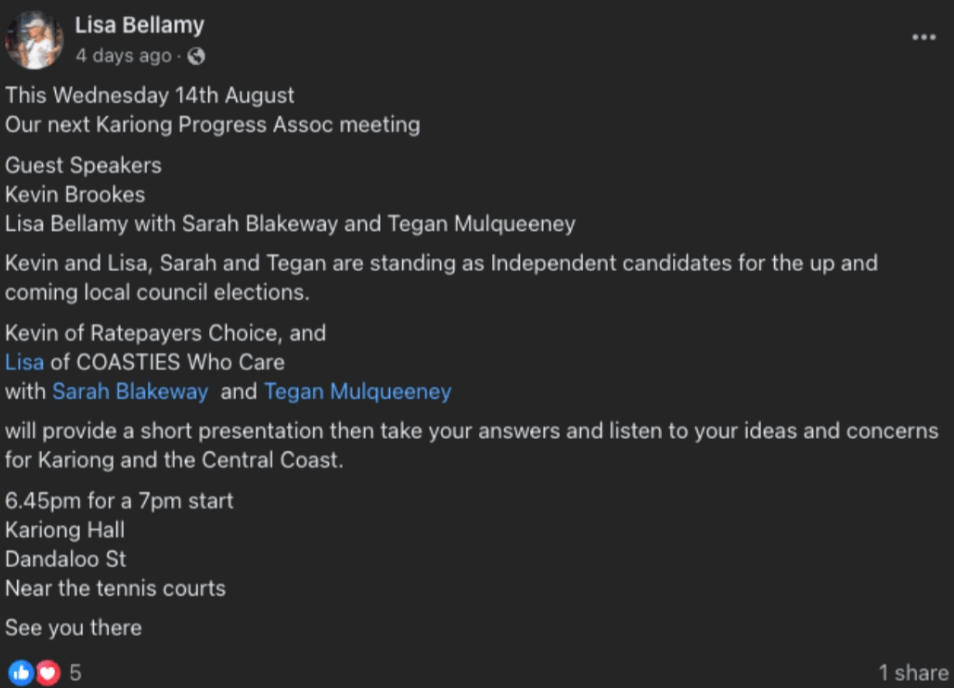

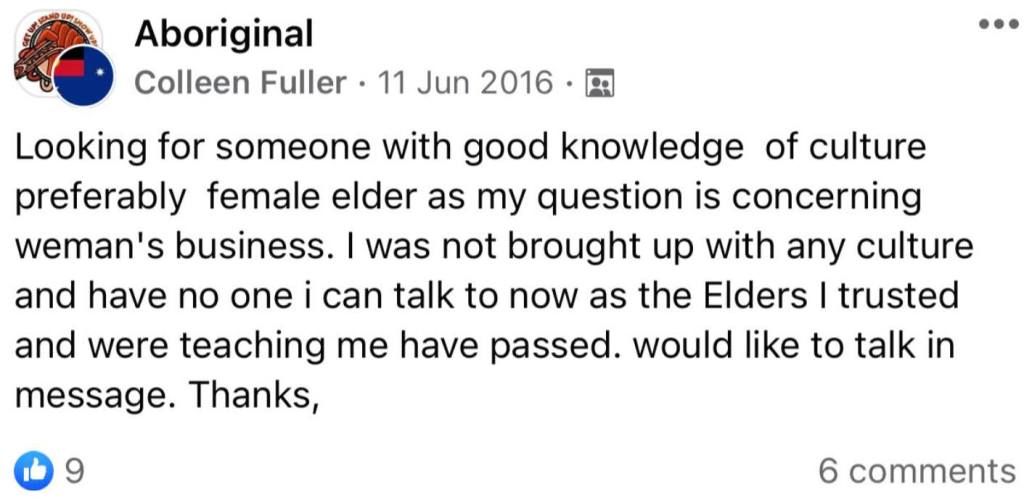

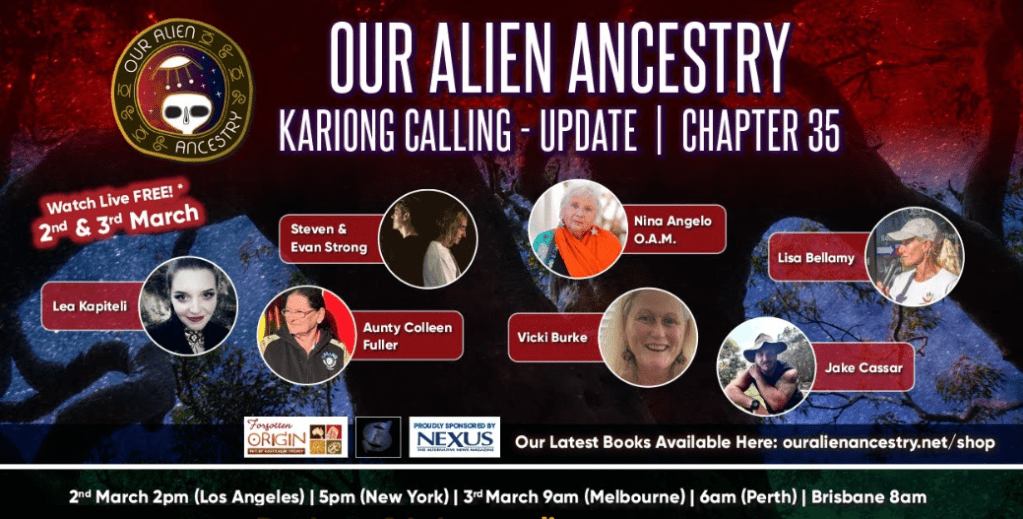

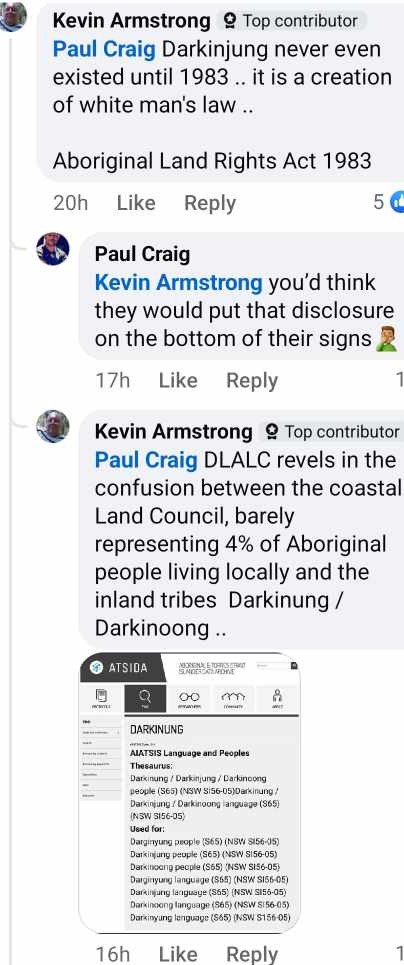

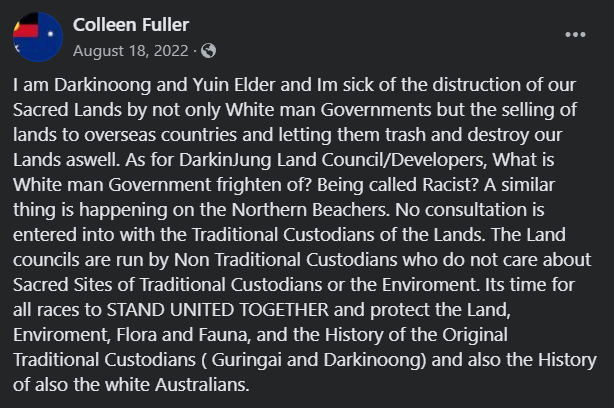

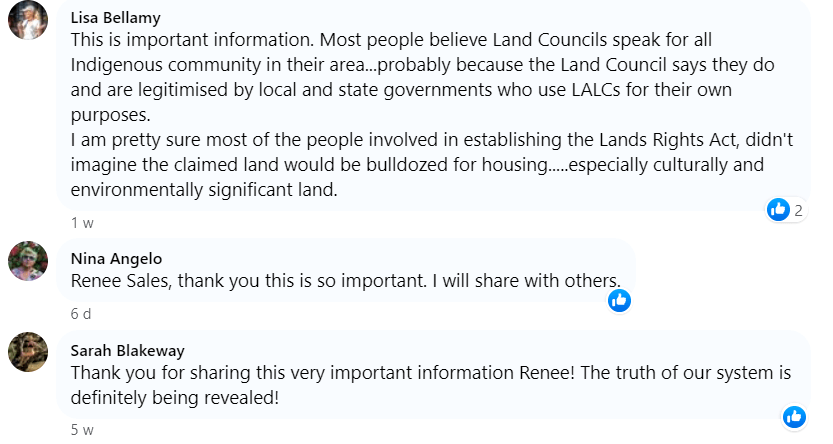

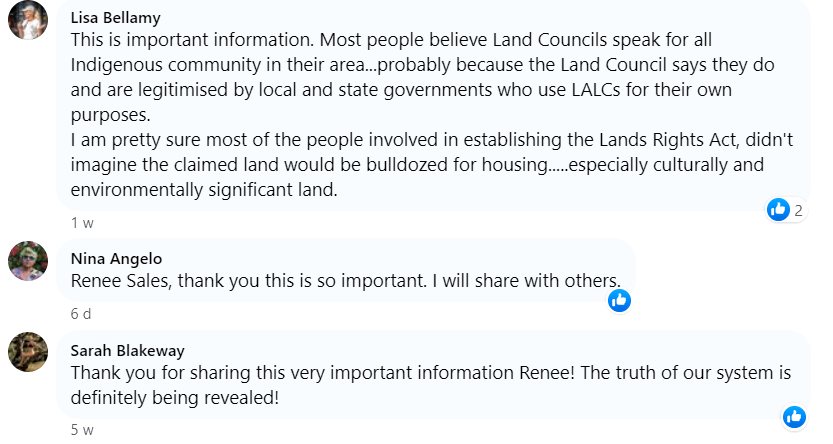

The current network of Goolabeen’s ideological heirs includes figures such as Jake Cassar, Nina Angelo, Lisa Bellamy, Colleen Fuller, and the GuriNgai group: each of whom has played a role in perpetuating falsehoods about Kariong’s history, asserting illegitimate custodianship, and undermining the sovereignty of both culturally and legally recognized Aboriginal people and authority in the region, including the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) (Cooke, 2025f).

Jake Cassar, in particular, has rebranded himself as an environmental defender, invoking the mystical narratives seeded by Spiers to justify his opposition to DLALC’s development projects (Cooke, 2025f).

He platforms fraudulent Aboriginal claimants like Beve Spiers, Colleen Fuller, and Tracey Howie, who falsely claims descent from Bungaree and Matora (Cooke, 2025f), and partners with identity fraud groups like the GuriNgai, amplifying their messages through protests, social media campaigns, and coordinated petitions (Cooke, 2025f).

Cassar’s rhetoric of sacred defense conceals a deeper project of spiritualized land possession (Cooke, 2025f). His invocation of “saving Kariong Sacred Lands” is not about protecting legitimate Aboriginal heritage; it’s about preserving a settler fantasy of Aboriginality that serves his own spiritual and political capital (Cooke, 2025f).

Nina Angelo, closely affiliated with both Cassar and the Strongs (Steven and Evan), continues to publicly promote Goolabeen’s spiritual legacy, often speaking of the “wisdom” passed down by Beve Spiers (Cooke, 2025f). Angelo’s version of allyship is laced with appropriation, retelling myths of Egyptian arrivals, star ancestors, and Kariong as a “portal,” all while excluding the voices of real Aboriginal custodians (Cooke, 2025f).

This is a hallmark of what is termed settler conspirituality: the fusion of New Age belief systems, white spiritual supremacy, and anti-government conspiracism under the guise of reconciliation and cultural respect (Cooke, 2025f).

This tendency is institutionalized through CEA’s affiliation with groups like Coasties Who Care, Save Kincumber Wetlands, My Place, and Walkabout Wildlife Sanctuary (Cooke, 2025f). These networks repeatedly promote the idea that DLALC isn’t a “real” Aboriginal organization and that the “true” custodians are those connected to Goolabeen’s followers and/or the GuriNgai identity fraud network (Cooke, 2025f).

The recourse to such figures allows settler environmentalists to assert that their opposition to Aboriginal land development is in fact an act of Aboriginal defense (Cooke, 2025f). This logic is not only disingenuous; it’s structurally violent. It replaces recognized Aboriginal governance with mythic pretenders and confers cultural legitimacy on settler activists through a process of performative Indigeneity (Cooke, 2025f).

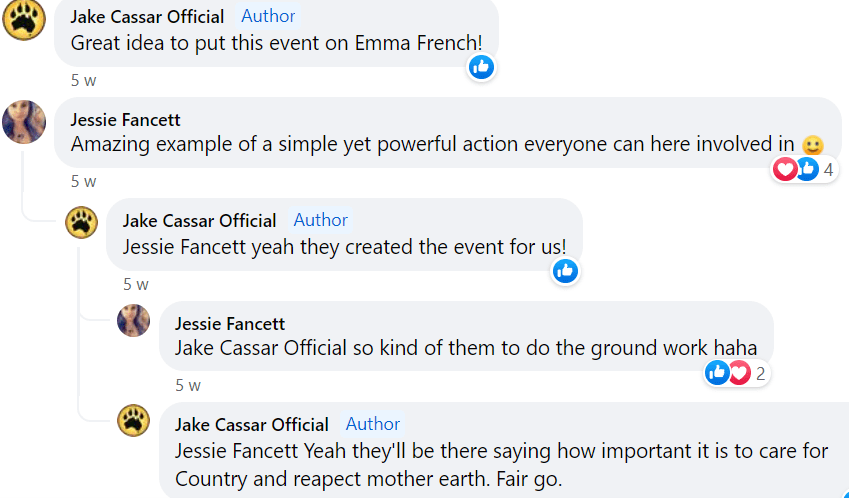

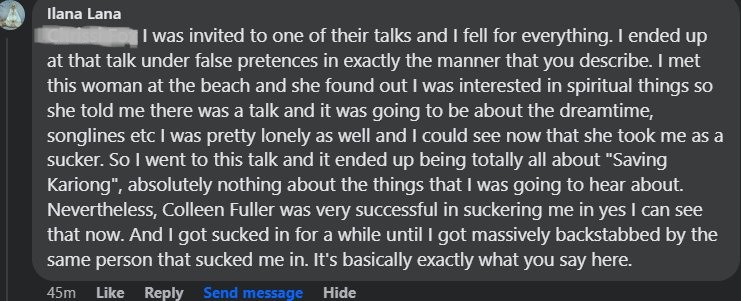

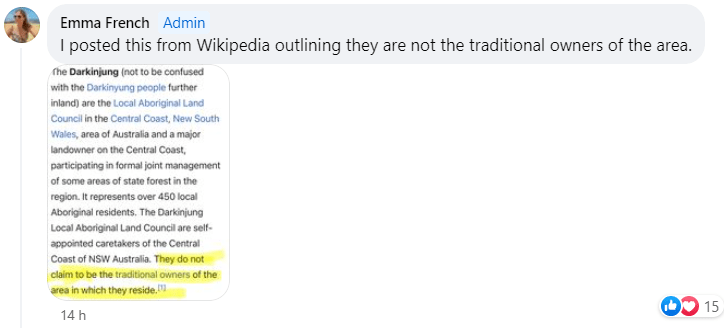

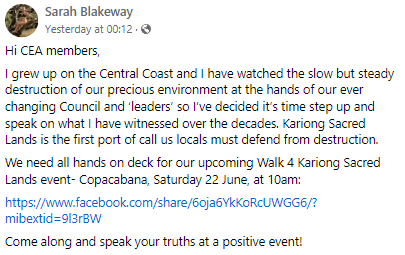

The case of Emma French, organizer of the “Walk for Kariong” event, further reveals this strategic re-enactment of Goolabeen’s legacy (Cooke, 2025f). In a 2024 interview, French stated that her group was “just walking” for the wildlife and that it was “not a protest” (Cooke, 2025f). Yet, her affiliations with CEA and her alignment with known frauds such as Colleen Fuller and Paul Craig show that the walk was part of a coordinated campaign to undermine DLALC authority (Cooke, 2025f).

Her statements conflating DLALC with “developers” and her expressed refusal to seek permission from 5-Lands Walk organizers demonstrate an entitlement rooted in settler spiritualism and a refusal to engage with Indigenous governance structures (Cooke, 2025f). As French herself admitted: “Talk to Jake Cassar. He does everything. I just do the graphic design” (Cooke, 2025f). This deference to Cassar’s authority, rather than to Aboriginal people, including DLALC representatives, is symptomatic of the cultic dimensions of the movement (Cooke, 2025f).

As Crabtree et al. (2020) note, settler cults often coalesce around a central figure whose charisma stands in for cultural legitimacy (Crabtree et al., 2020). In the case of CEA and its affiliates, Jake Cassar has come to occupy precisely this role, channeling Goolabeen’s legacy into a new mythology of settler custodianship (Cooke, 2025f).

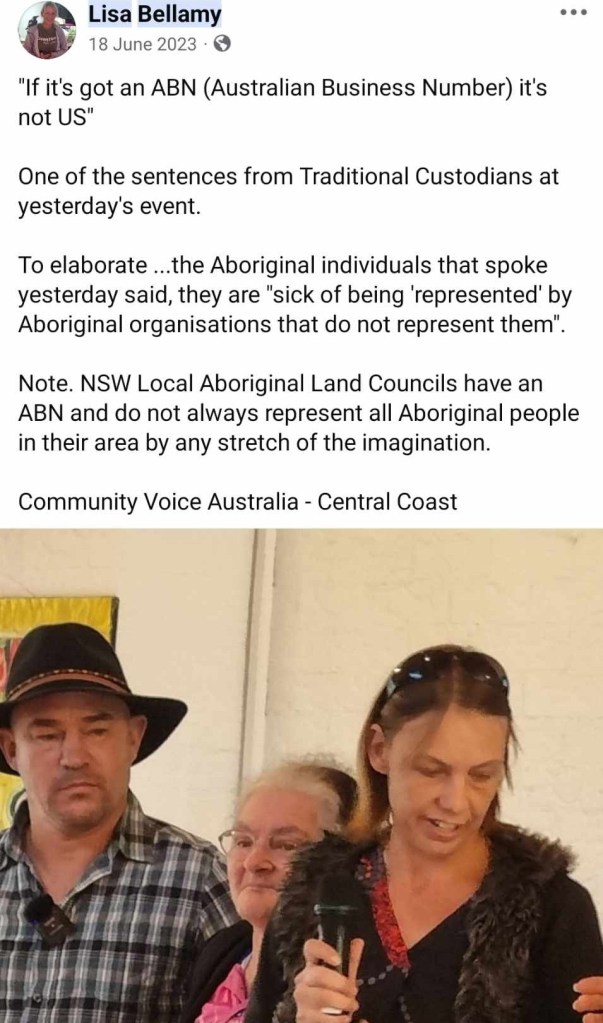

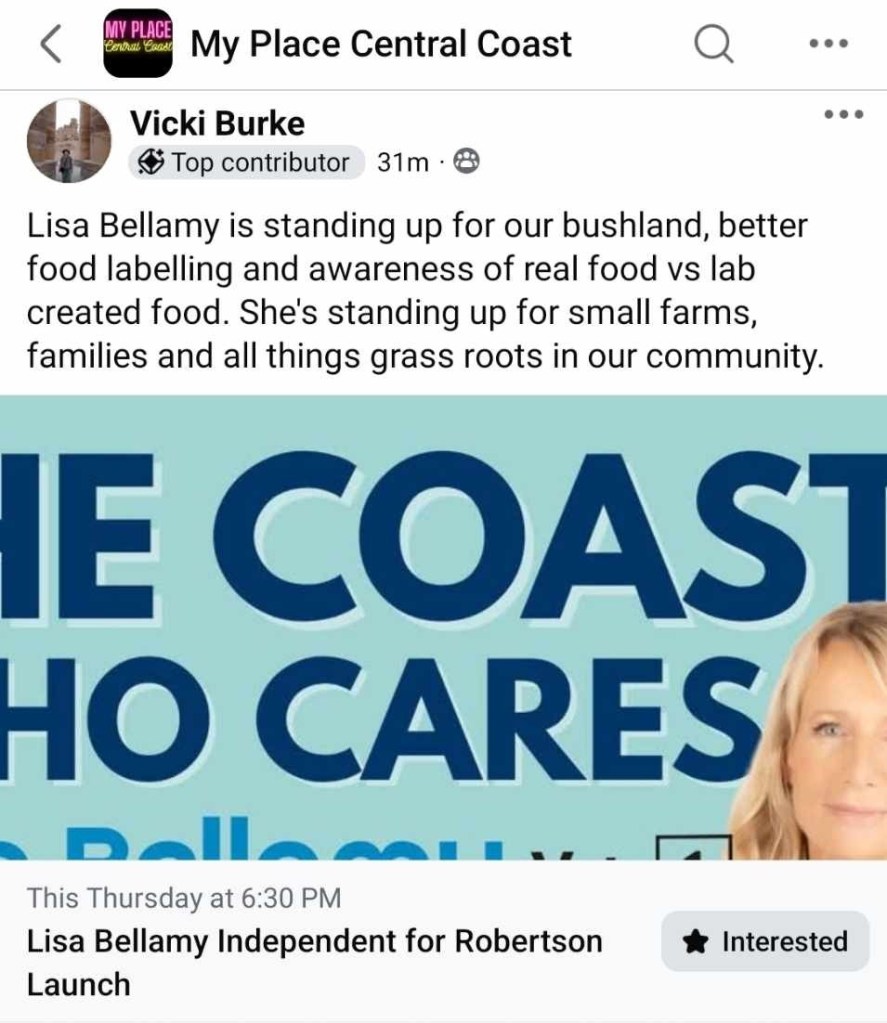

Lisa Bellamy and the Mythos of Faux Custodianship

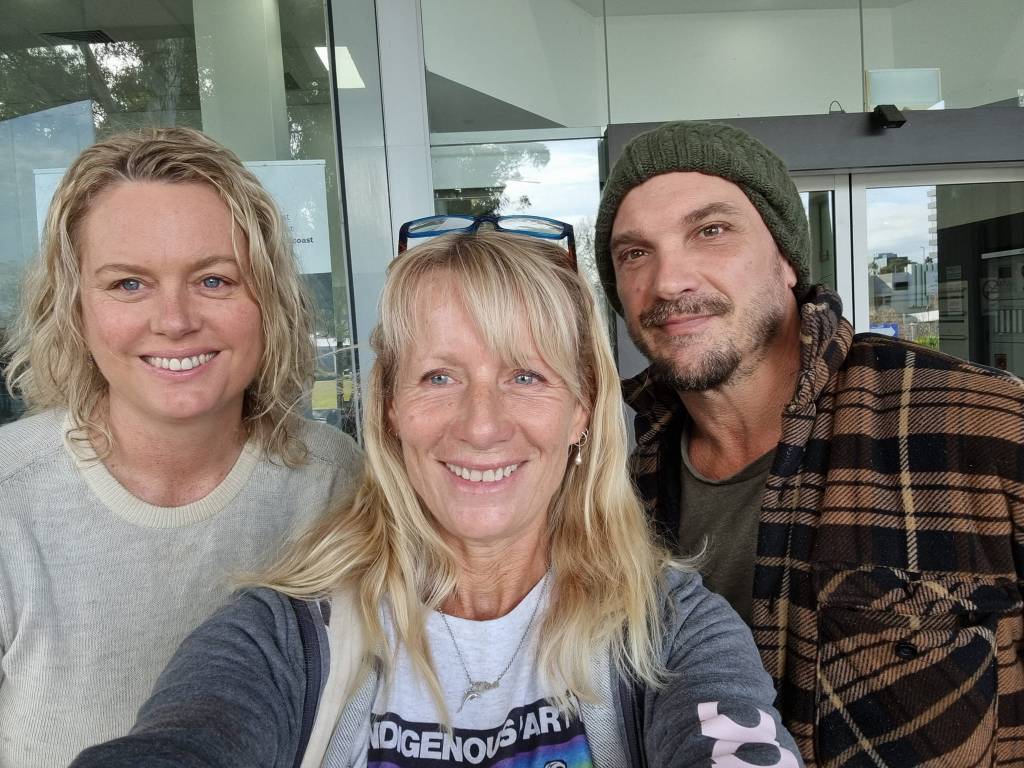

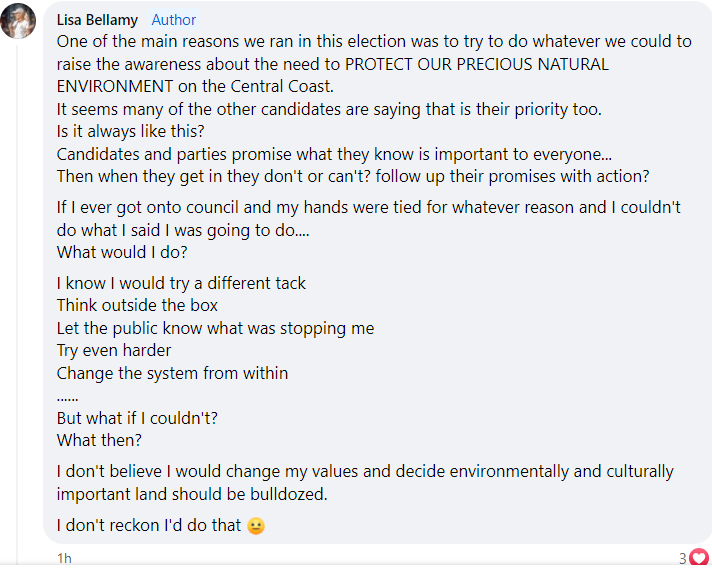

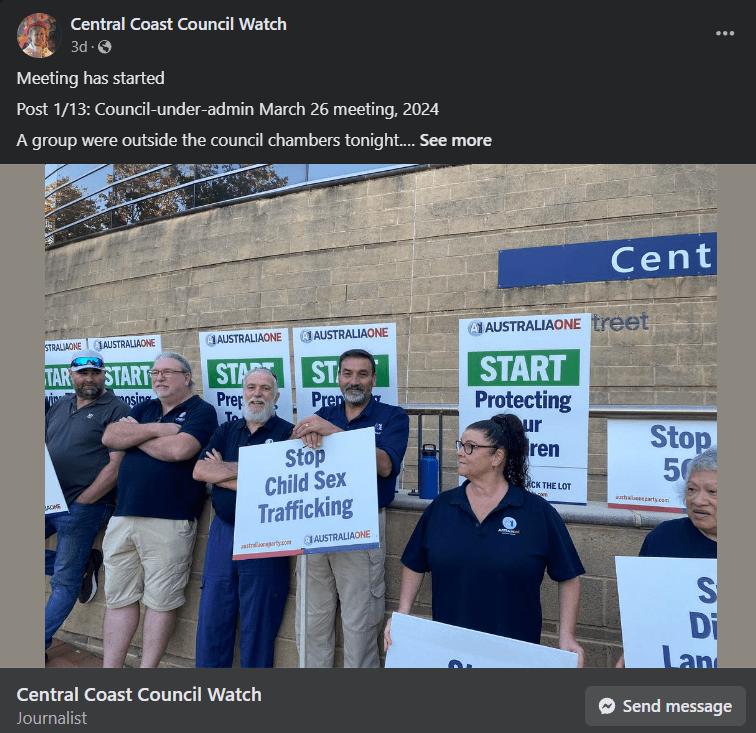

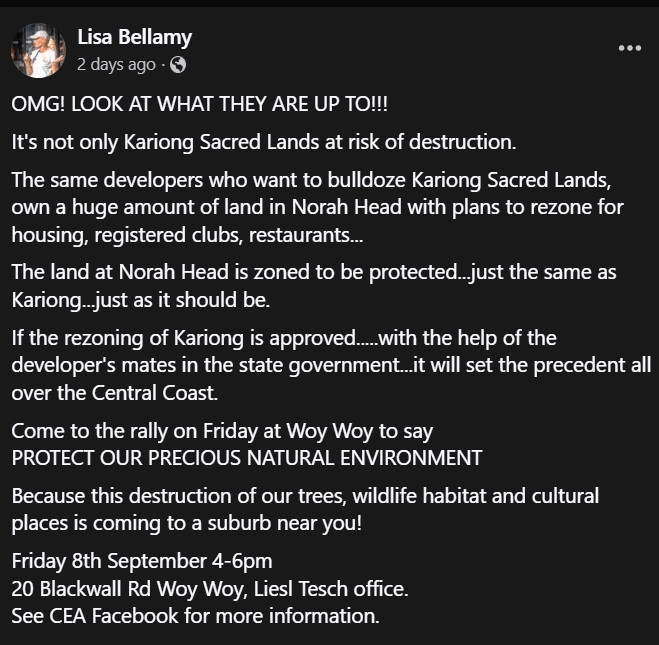

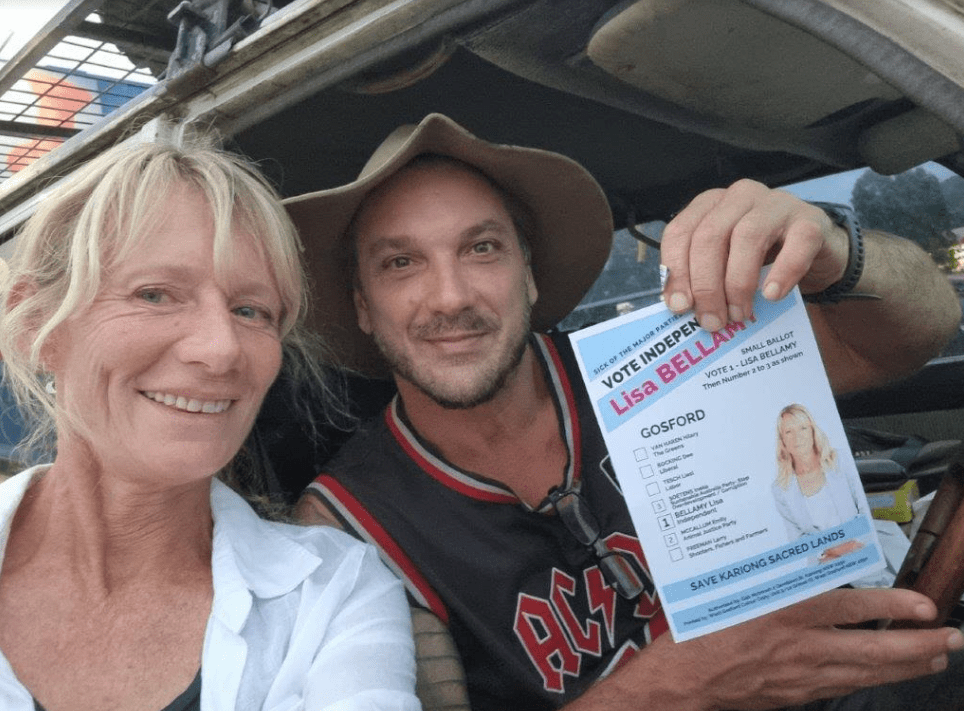

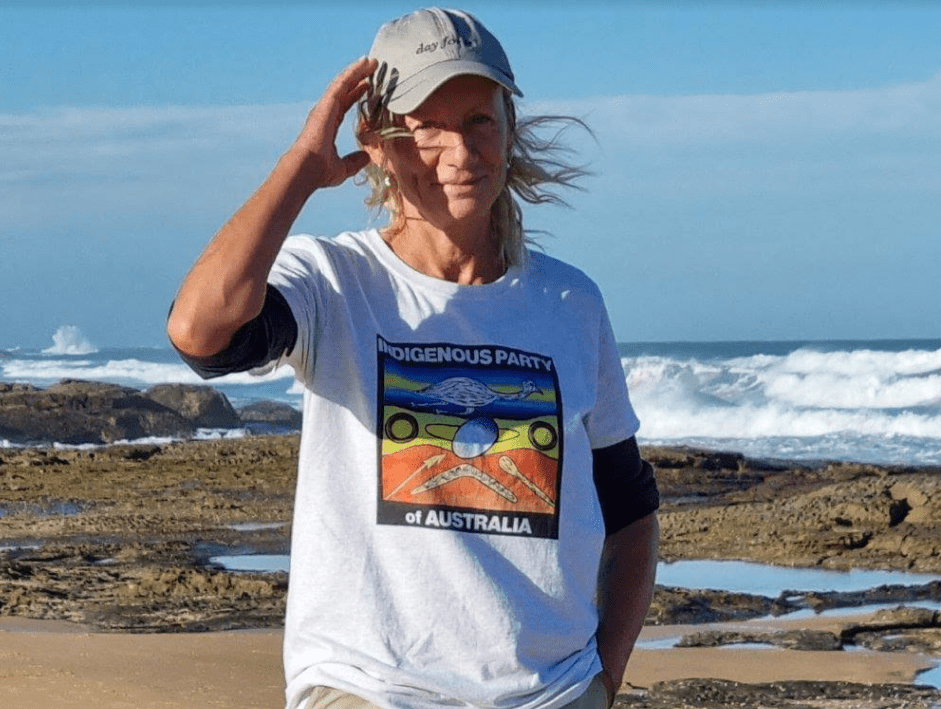

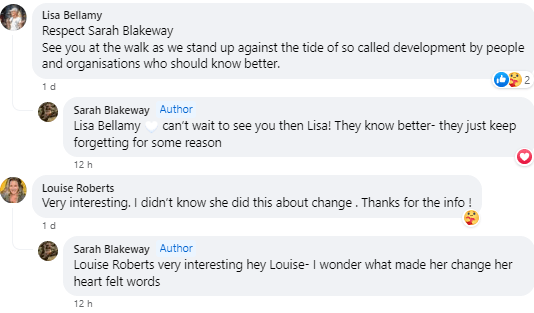

Lisa Bellamy has emerged as a key actor within the interwoven networks of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), Save Kariong Sacred Lands, Save Kincumber Wetlands, and Coasties Who Care (Cooke, 2025f). Since undertaking a “bushcraft” course with Jake Cassar, Bellamy has positioned herself at the center of a constellation of settler-led movements opposing Aboriginal land use, all while claiming to support Aboriginal people and cultural values (Cooke, 2025f).

Her public rhetoric, however, reveals a more complex and troubling alignment: one that consistently reinforces false claims to Aboriginal identity, undermines the authority of legitimate Aboriginal landholders, and performs a settler-spiritual alternative to Aboriginal sovereignty (Cooke, 2025f).

Bellamy’s activism is most visible in protest events and digital campaigns such as the Kariong Sacred Lands rallies, where she speaks alongside known identity frauds including Tracey Howie, Colleen Fuller, and Paul Craig (Cooke, 2025f). Rather than challenging or distancing herself from these individuals, Bellamy platformed and amplified their narratives, directly contributing to the broader disinformation ecosystem surrounding Kariong (Cooke, 2025f). In public speeches, she routinely invokes “sacredness” and “ancestors,” terms that resonate with spiritual authority, but which are deployed without any confirmation of cultural legitimacy or connection to recognized traditional owners (Moreton-Robinson, 2015; Cooke, 2025f).

The racial politics underpinning Bellamy’s activism are subtle but significant (Cooke, 2025f). She promotes herself as a “bridge-builder” between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, yet consistently aligns with pseudo-Aboriginal figures rejected by both state-recognized and community-recognized Aboriginal groups (Cooke, 2025f).

In doing so, she enacts what Philip Deloria (1998) describes as the “performance of Indianness,” where settler subjects assume the symbolic trappings of Aboriginal identity to claim moral authority and territorial legitimacy (Deloria, 1998; Cooke, 2025f). Bellamy’s use of the GuriNgai identity, which is genealogically and historically false, further entrenches the settler mimicry at play within CEA’s networks (Cooke, 2025f).

This mimicry has material consequences (Cooke, 2025f). As seen in her leadership within the Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign, Bellamy has worked to frame the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) as a “developer” rather than a community-controlled Aboriginal entity (Cooke, 2025f).

Through emotive language, spiritual aesthetics, and carefully curated protest images, Bellamy helped invert the narrative: DLALC became the threat, and settler-activist groups became the defenders of Country (Cooke, 2025f).

This discursive shift isn’t simply rhetorical. It undermines the legislative intent of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), which affirms the rights of Aboriginal people to manage and develop land returned under land rights claims (NSW Aboriginal Land Council, 2022; Cooke, 2025f).

By presenting settler-led environmentalist resistance as Aboriginal-led cultural protection, Bellamy and her network obscure the actual structures of Aboriginal land governance and replace them with a spiritualized settler authority (Cooke, 2025f).

Bellamy’s activity must also be read in the context of her affiliation with the Indigenous-Aboriginal Party of Australia, a minor political party that has been publicly criticized for enabling fraudulent claims to Aboriginal identity and for advancing anti-Land Council rhetoric (Cooke, 2023). Her association with the party’s founder, Uncle Owen Whyman, and her public endorsements of non-Aboriginal activists claiming cultural status further embed her within a political strategy of cultural substitution (Cooke, 2025f).

This tactic mirrors what Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) describes as the settler’s desire to possess and represent Aboriginality, not in service of solidarity, but to displace the authority of those who are entitled to speak for Country (Moreton-Robinson, 2015; Cooke, 2025f).

The cultic dynamics of Bellamy’s activism are also evident in her continued alignment with Jake Cassar and the charismatic narrative control he exerts over the CEA community (Cooke, 2025f).

Bellamy’s social media and campaign materials often echo Cassar’s language, promoting a worldview where spiritual warfare, environmental urgency, and ancestral duty converge in a metaphysical struggle between “truth-tellers” and “traitors” (Cooke, 2025f). This Manichaean logic is common in conspiritual movements (Asprem & Dyrendal, 2015; Cooke, 2025f). It positions Bellamy and her allies not just as activists, but as vessels of sacred mission, imbuing their settler resistance with the aura of divine mandate (Cooke, 2025f).

Such framing also obscures the violence implicit in their actions (Cooke, 2025f). Bellamy has publicly encouraged people to oppose DLALC projects without engaging Aboriginal decision-makers, participating in misinformation campaigns that have incited community division and cultural harm (Cooke, 2025f).

Her claim to stand “for the community” becomes a hollow gesture when examined alongside her repeated endorsements of unverified or disproven identity claimants, her opposition to Aboriginal-led development, and her willingness to frame herself as a protector of Country, and as a ‘custodian’ without any recognized right to do so (Cooke, 2025f).

Identity Fraud, Settler Spiritualism, and the GuriNgai Cult of Kariong

The GuriNgai group, prominently supported by Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), constitutes a central node in the performance of false Aboriginal identity on the Central Coast (Cooke, 2025f). This group, led by non-Aboriginal individuals such as Tracey Howie, Laurie Bimson, Neil Evers, Colleen Fuller, and others, asserts a fraudulent connection to a so-called “GuriNgai” or “Wannagine” people (Cooke, 2025f). These claims have no verifiable genealogical, anthropological, or linguistic foundation. In fact, they have been repeatedly discredited by historians, linguists, Aboriginal community leaders, and the Aboriginal Land Rights network (Cooke, 2025f; Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024).

CEA’s decision to platform these individuals isn’t incidental. It’s a strategic act of cultural substitution (Cooke, 2025f). Across numerous protests, livestreams, and media campaigns, figures like Jake Cassar, Lisa Bellamy, and Vicki Burke amplify the voices of false claimants while systematically excluding recognized Aboriginal leaders such as representatives of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) (Cooke, 2025f). This inversion isn’t simply a matter of representation. It actively displaces Aboriginal authority, erasing the governance structures enshrined in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) and supplanting them with settler-authored alternatives (Cooke, 2025f).

The cultic dimensions of the GuriNgai movement are particularly evident in the shared mythology, initiatory narratives, and charismatic origin stories surrounding figures such as “Goolabeen” (Beve Spiers) (Cooke, 2025f). Spiers, a non-Aboriginal woman, mentored Tracey Howie and Evan Strong in the early 2000s, initiating them into what was framed as Aboriginal spiritual knowledge (Cooke, 2025f).

These claims, recorded in livestreams and public videos as recently as November 2023, form the pseudo-spiritual bedrock of the GuriNgai cult (Cooke, 2025f). Men like Evan and Steven Strong now describe themselves as “initiated” into Aboriginality, claiming esoteric knowledge received from Spiers and projecting themselves as guardians of sacred lore (Cooke, 2025f). This is a textbook case of settler spiritualism masquerading as Indigenous tradition (Cooke, 2025f).

The racism embedded in these appropriations is rarely overt, but is structurally entrenched (Cooke, 2025f). The logic of white spiritual superiority underpins the cult’s internal narrative: that they, as spiritually “awakened” non-Aboriginals, are better equipped than actual Aboriginal people to protect Country, hold ceremony, or speak for ancestors (Cooke, 2025f).

This is a neo-colonial fantasy, rooted in what Deloria (1998) describes as the desire to replace the Indigenous subject with the settler subject bearing Indigenous traits (Deloria, 1998; Cooke, 2025f).

Within this schema, authentic Aboriginal voices are cast as impediments, too compromised, too modern, or too “corporatised”, to be trusted with custodianship (Cooke, 2025f). Meanwhile, the settler-spiritual group presents itself as both ancestral and alternative, a fusion of environmental activism, conspiracy spirituality, and mythopoetic mimicry (Cooke, 2025f).

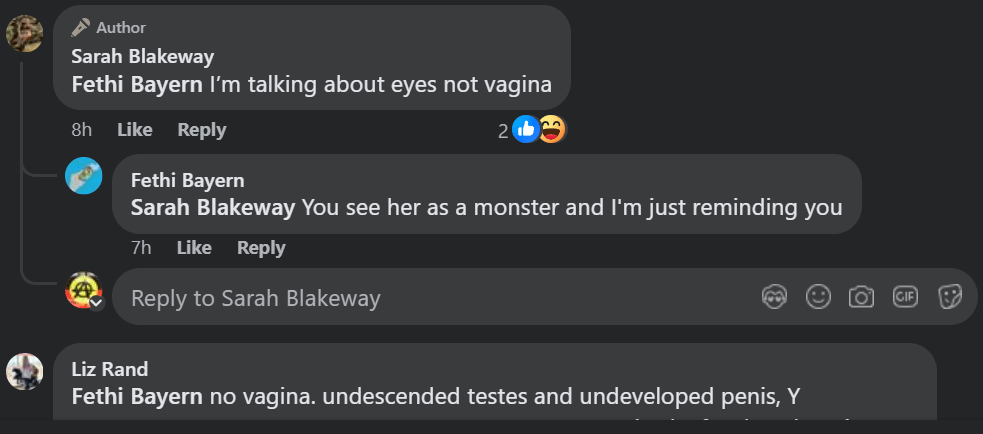

The November 2023 livestream involving Bellamy, Fuller, and the Strongs presents a vivid illustration (Cooke, 2025f). Across a series of recorded broadcasts, the group makes sweeping and often incomprehensible claims about “original people,” “intergalactic ancestors,” “cosmic law,” and “quantum Aboriginality” (Cooke, 2025f).

These discourses draw heavily on New Age tropes and sovereign citizen language, blending pseudo-science with racial mysticism (Cooke, 2025f). Such rhetoric is not only culturally harmful; it’s politically violent (Cooke, 2025f). It undermines the authority of Aboriginal people by introducing a counterfeit cultural paradigm, one that cannot be contested through legal or genealogical means because it is constructed as metaphysical truth (Cooke, 2025f).

The social consequences of these actions are real (Cooke, 2025f). As reported in November 2023, sacred Aboriginal sites in the Kariong area were vandalized shortly after several livestreams encouraged public trespass and unauthorized visitation to sensitive sites (ABC News, 2023; Cooke, 2025f). Individuals affiliated with the GuriNgai group have been documented encouraging their followers to “go do what you want” on Country, dismissing Aboriginal protocols, and defying management regimes put in place by Aboriginal corporations (Cooke, 2025f). These behaviors reflect not only arrogance but also a denial of the rights of Aboriginal communities to control access to their land and culture (Cooke, 2025f).

CEA’s amplification of these figures, through interviews, protest footage, social media tagging, and campaign alignment, constitutes a digital infrastructure of disinformation and cultural harm (Cooke, 2025f). By legitimizing the GuriNgai cult, CEA facilitates the broader project of Indigenous identity fraud, contributing to a post-truth political economy in which false claimants gain access to media, funding, and social influence at the expense of genuine Aboriginal people (Cooke, 2025f).

Save Kincumber Wetlands: A Case Study in Manufactured Crisis

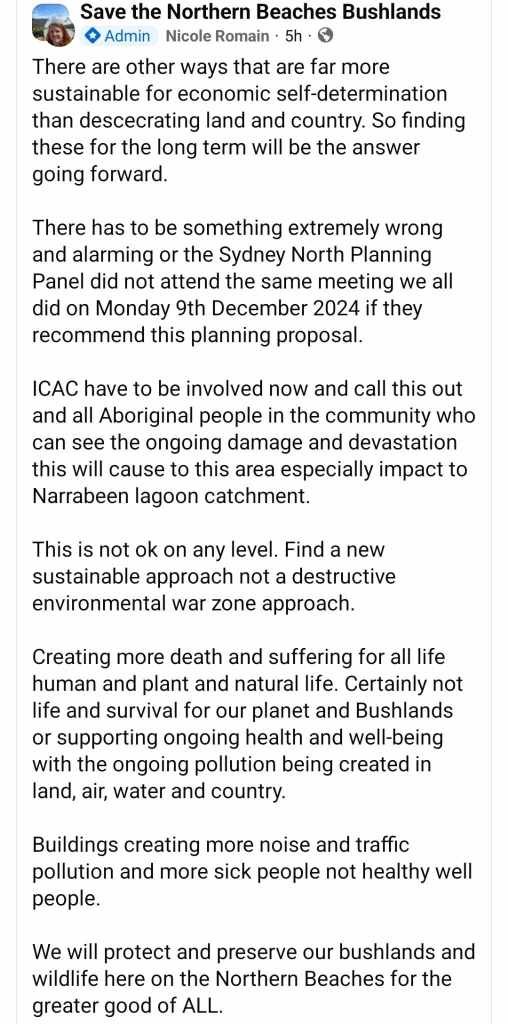

The “Saving Kariong Sacred Lands” campaign, orchestrated by Jake Cassar and Lisa Bellamy of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), exemplifies a settler-conspiritualist movement deeply entangled with pseudo-Indigenous claims and white environmental populism (Cooke, 2025g).

These campaigns operate not as legitimate ecological protests. Rather, they function as ideological offensives against Aboriginal self-determination and land rights (Cooke, 2025g). Drawing upon disingenuous faux-environmental narratives, they frame Aboriginal governance as incompatible with imagined localized spiritual ecologies and community values (Cooke, 2025g).

The defining feature of the Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign is its pre-emptive hysteria (Cooke, 2025g). As of June 2025, there is no formal development proposal before council for the site owned by Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) (Cooke, 2025g). No verified environmental risk has been formally identified, nor have sacred sites been declared endangered by qualified Aboriginal authorities (Cooke, 2025g).

Despite this, CEA-aligned activists have staged rallies, marches, published alarming press releases, and launched social media campaigns denouncing an entirely imagined ecological apocalypse (Cooke, 2025g). This fiction has been enthusiastically propagated by Coast Community News (CCN), which has published multiple articles presenting the protest as an urgent response to imminent destruction, amplifying the perception of a crisis without confirming whether a development proposal even exists (Coast Community News, 2025b; Cooke, 2025g).

Online platforms such as the Coast Environmental Alliance Facebook group and Save Kincumber Wetlands amplify these narratives with hyperbolic imagery, references to threatened species, and unfounded accusations against DLALC (Cooke, 2025g). AllEvents listings for CEA rallies and CCN’s uncritical coverage further normalize the protest campaign as legitimate, despite the absence of environmental assessments or consultation, including with DLALC (Cooke, 2025g).

In none of these reports has a DLALC representative been given voice, nor has any journalist acknowledged the absence of a formal application (Cooke, 2025g). Instead, the entire campaign hinges on rumor, repetition, and racialized distrust: a settler fantasy in which Aboriginal people are refigured as desecrators of land, and settler activists as its sacred protectors (Cooke, 2025g).

This pattern isn’t new. The Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign closely mirrors earlier CEA-aligned protests, including those at Bambara (Kariong Sacred Lands) and Lizard Rock (Patyegarang) (Cooke, 2025g). In each case, false Aboriginal identity claims, eco-spiritual aesthetics, and settler-fronted sacredness are deployed to block Aboriginal land council development proposals (Cooke, 2025g).

At Kariong, protesters invoked the debunked Gosford Glyphs and aligned with pseudoarcheologists and known far-right figures (Cooke, 2025g). At Lizard Rock, the GuriNgai faction was again mobilized to oppose the legitimate development of land owned by the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (Cooke, 2025g). These events are not isolated; they’re structurally coordinated campaigns of settler reenchantment and white possessive environmentalism (Moreton-Robinson, 2015; Cooke, 2025g).

When viewed collectively, these campaigns form a pattern of counter-Aboriginal activism masquerading as ecological care (Cooke, 2025g). CEA and its allies routinely appropriate Indigenous language, symbolism, and ritual to elevate their authority while denying Aboriginal people the right to act as custodians of our own land (Cooke, 2025g).

They create a simulacrum of traditional protest, complete with fake Elders, faux ceremonies, and manipulated heritage narratives (Cooke, 2025g).

In doing so, they not only derail vital housing and economic initiatives for Aboriginal people but delegitimize the very idea of Aboriginal environmental and cultural governance (Cooke, 2025g).

The Kincumber protest is simply the latest expression of this trend. Its broader significance lies in how it connects to a settler network of cultural imposture, environmental theatre, and conspiracist opposition to Aboriginal sovereignty (Cooke, 2025g). The tactics, manufacturing controversy, dominating media narratives, invoking fantasy spiritual sites, are replicated across the region (Cooke, 2025g).

Understanding Save Kincumber Wetlands requires understanding the broader CEA movement: not as a grassroots conservation network, but as a settler cult that weaponizes the environment to erase Aboriginal land rights (Cooke, 2025g).

Apocalyptic Affect, QAnon Logic, and the Storm as Settler Revelation

The term “The Storm,” central to QAnon’s apocalyptic cosmology, functions as a floating signifier of catastrophe and redemption (Cooke, 2025e). It evokes spiritual warfare, systemic collapse, and the coming of moral reckoning (Cooke, 2025e).

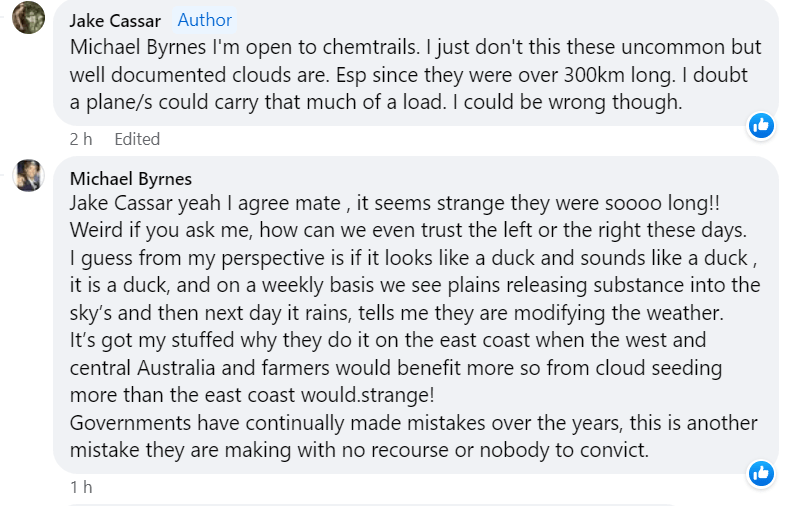

While not explicitly publicly invoked by Jake Cassar, its thematic resonance permeates the rhetoric of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar frequently speaks of hidden forces, sacred truths under siege, and the need for spiritual warriors to rise up against corruption, classic apocalyptic motifs drawn from conspiratorial and millenarian traditions (Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar’s messaging draws heavily on QAnon-adjacent tropes: elite betrayal, covert knowledge, and spiritual battle (Cooke, 2025e). His framing of DLALC developments as “cultural crimes” committed by spiritually illegitimate authorities echoes QAnon’s portrayal of mainstream institutions as morally compromised (Cooke, 2025e). Through Facebook posts, video content, and live speeches, Cassar offers his followers a redemptive narrative: they are the chosen few, awakened to the truth of sacred land under threat, called to act before it is too late (Cooke, 2025e).

This narrative generates what scholars term “apocalyptic affect”, an emotional register comprising dread, transcendence, grief, and resolve (Cooke, 2025e). Followers are not only fearful of ecological collapse, but spiritually energized by the opportunity to participate in a mythic battle (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s rhetoric converts anxiety into a moral mission, positioning CEA as both seer and savior (Cooke, 2025e).

These dynamics mirror the logic of QAnon, in which secrecy is spiritualized and revelation is personal (Cooke, 2025e). Believers feel that they alone perceive the hidden connections that expose the enemy’s schemes (Cooke, 2025e). For Cassar’s audience, the DLALC isn’t simply a land council; it’s a symbol of a larger betrayal of ancestral law and natural truth (Cooke, 2025e). Settler resistance is thus sanctified as a moral obligation (Cooke, 2025e).

Importantly, the affective structure of CEA’s movement resists empirical challenge (Cooke, 2025e). As in QAnon, dissenters are cast as either naïve or complicit (Cooke, 2025e). Counter-evidence is dismissed as propaganda (Cooke, 2025e).

The emotional architecture of the movement insulates it from critique while deepening participants’ sense of righteousness and urgency (Cooke, 2025e). Through this emotional and epistemological mechanism, settler conspirituality reverses the meaning of sovereignty (Cooke, 2025e).

Aboriginal-led development becomes desecration. Settler-led activism becomes sacred defense (Cooke, 2025e). The storm, in this framework, isn’t only a metaphor for collapse. It’s a revelation of settler redemption, a ritualized drama of rebirth through spiritual struggle (Cooke, 2025e).

Settler Identity, Masculinity, and Mythmaking

Jake Cassar’s appeal is inseparable from the cultural coding of rugged, outdoorsy masculinity and settler nationalism (Cooke, 2025e). His image evokes a heroic archetype: bushman, warrior, spiritual guide, fused with frontier aesthetics and survivalist ethos (Cooke, 2025e). This persona plays into long-standing tropes of white Australian identity rooted in land mastery, physical resilience, and masculine independence (Cochrane et al., 2024; Cooke, 2025e).

In the world of settler conspirituality, masculinity is moralized (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s survivalism is more than an aesthetic; it’s cast as a sacred vocation (Cooke, 2025e). His bushcraft skills are imbued with spiritual meaning, presented as forms of ancestral remembrance and protection of sacred land (Cooke, 2025e). He becomes a hybrid figure, part sage, part warrior, defending the Earth against desecration (Cooke, 2025e). This fusion reflects what cultural theorists describe as “apocalyptic manhood,” in which existential threat justifies hyper-masculine heroism (Renner et al., 2023; Cooke, 2025e).

These performances are deeply political (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s masculinity is tied to settler narratives of rightful belonging and protective authority (Cooke, 2025e). He asserts that he is defending not just nature, but a spiritual order embedded in the Australian bush (Cooke, 2025e). This masculine settler spirituality mimics Aboriginal concepts like caring for Country, but displaces them by asserting white sovereignty in spiritual form (Cooke, 2025e). It enacts what Wolfe (2006) termed the logic of elimination, not simply by physical violence, but by symbolic supersession (Wolfe, 2006; Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar’s mythmaking also relies on the production of epic storylines: quests, sacred missions, betrayals, and awakenings (Cooke, 2025e). His social media content is saturated with mythic imagery; ancient portals, warrior protectors, cosmic wisdom, and hidden enemies (Cooke, 2025e). These narratives cultivate a mythopoeic atmosphere in which followers are not merely activists, but spiritual warriors (Cooke, 2025e). The stakes are cosmic, and so are the rewards (Cooke, 2025e).

Ultimately, Cassar’s settler identity isn’t merely individual. It’s performative, contagious, and collective (Cooke, 2025e). Through ritual, storytelling, and charismatic leadership, he enables his followers to inhabit a shared mythos (Cooke, 2025e). They are inducted into a narrative that affirms their belonging to land, history, and truth; while masking the dispossession of the First Peoples whose stories and symbols they appropriate (Cooke, 2025e).

Emotional Communities and the Politics of Belonging

At the heart of CEA’s success lies its capacity to generate emotional communities; affective networks of belonging built through shared ritual, grievance, and spiritualized narrative (Cooke, 2025e). This echoes the broader dynamics of QAnon and other conspiratorial movements, where belief is not merely cognitive but relational, embodied, and affective (Cooke, 2025e).

Jake Cassar’s followers aren’t just environmental activists. They are inducted into a sacred narrative of awakening and protection, a community bonded by shared revelation and perceived persecution (Cooke, 2025e). Events such as forest walks, “sacred site” vigils, yowie expeditions, and communal ceremonies serve as affective intensifiers, building trust and solidarity while reinforcing oppositional identity (Cooke, 2025e).

Participants experience a sense of transformative purpose, emotional catharsis, and moral certainty; all hallmarks of high-demand social environments often described as cultic (Crabtree et al., 2020; Cooke, 2025e).

CEA’s emotional architecture is characterized by gratitude rituals, public displays of spiritual commitment, and regular affirmations of mission (Cooke, 2025e). In Facebook groups and community meetings, followers share testimonials of awakening, express outrage at DLALC developments, and reaffirm each other’s roles as guardians of sacred land (Cooke, 2025e).

Emotional labor is central (Cooke, 2025e). Followers are encouraged to cry, rage, heal, and commune, producing what Ahmed (2004, 2014) terms an “affective economy” where emotions circulate and bind the group together (Ahmed, 2014; Cooke, 2025e).

These emotional communities aren’t apolitical. They function as affective counterpublics; spaces where settler identity is reimagined through spiritual communion and political opposition (Cooke, 2025e). They invert the usual dynamics of marginalization, presenting CEA members as an oppressed spiritual minority resisting hegemonic authority (Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar’s followers often frame themselves as victims of censorship, institutional betrayal, and cultural erasure (Cooke, 2025e). This persecutory inversion mirrors the populist logics of QAnon, where power is seen as illegitimate unless it aligns with personal revelation and communal truth (Phillips, 2025; Cooke, 2025e).

Within CEA, ritual practice plays a central role in this emotional formation (Cooke, 2025e). Followers engage in what might be termed ritual bricolage, piecing together elements of Aboriginal ceremony, such as smoking, dance, and storytelling, with settler mythologies and New Age practices (Cooke, 2025e).

These ceremonies are not only symbolic acts of solidarity but also tools of cultural mimicry and identity substitution (Cooke, 2025e). Specific performances, like yowie tracking expeditions and sacred vigils, often include gestures, chants, or narratives appropriated from Aboriginal cosmology but stripped of cultural context or authority (Cooke, 2025e). This dynamic aligns with Sara Ahmed’s (2014) concept of the “stickiness” of emotions; how affect adheres to particular figures or symbols to construct communal identity (Ahmed, 2014; Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar himself becomes one such figure of stickiness, embodying grief, rage, love, and truth (Cooke, 2025e). Through his emotional cues, anguish at destruction, joy at communion, solemnity in ritual, he teaches followers how to feel and to whom those feelings should be directed (Cooke, 2025e).

Gender dynamics also play a role (Cooke, 2025e). CEA valorizes masculine protector roles through Cassar’s bushcraft and warrior ethos while simultaneously inviting nurturing, intuitive feminine identities into the circle through rituals of care, gratitude, and emotional openness (Cooke, 2025e).

These gendered affective roles contribute to the internal structure of the community and reinforce narratives of balanced, sacred harmony (Cooke, 2025e). However, they also mask the settler power dynamics at play, giving the appearance of decolonial healing while reinscribing colonial hierarchies (Cooke, 2025e).

Belonging in CEA is constructed through emotional resonance, but also through symbolic exclusion (Cooke, 2025e). Indigenous land councils like DLALC are not just bureaucratic adversaries. They are cast as emotional villains, desecrators of sacred ecology, and betrayers of cultural truth (Cooke, 2025e).

The result is a politics of belonging that requires the rejection of Indigenous authority in order to affirm settler spiritual purity (Cooke, 2025e). As such, the rituals of emotional bonding produce a sense of innocence and moral superiority that forecloses self-reflection (Cooke, 2025e).

This sacralized boundary between insider and outsider renders dialogue with Aboriginal voices nearly impossible (Cooke, 2025e). Any challenge is reframed as an attack on the group’s spiritual identity, leading to further emotional intensification and epistemic closure (Cooke, 2025e).

Platforms of Prophecy: Social Media Spectacle and the Rituals of Conspiritual Community

The success of settler conspiritual movements like the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) is inseparable from their use of social media as a platform for digital ritual and spectacle (Cooke, 2025e). In these online spaces, spiritual populism converges with algorithmic amplification, turning conspiracy into community and spectacle into belief (Cooke, 2025e). Jake Cassar’s charisma, spiritual rhetoric, and aesthetic curation function synergistically in digital ecologies to create a sacred space of emotional resonance and symbolic warfare (Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar’s posts across platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are richly affective (Cooke, 2025e). They feature images of sacred trees, sunset vigils, misty landscapes, and ritual gatherings infused with language of spiritual urgency and divine mission (Cooke, 2025e). These digital artifacts aren’t simply expressive; they’re performative, constructing an immersive cosmology in which followers are recruited into an enchanted war for Country (Cooke, 2025e).

Kalpokas (2018) calls this dynamic “post-truth aesthetics,” where emotional veracity trumps empirical evidence and where the circulation of affect becomes epistemological proof (Kalpokas, 2018; Cooke, 2025e). As Van Badham (2021) argues, the aesthetic grammar of conspiracy movements like QAnon uses emotionally charged imagery and narrative immersion to override rational critique, a strategy clearly echoed in Cassar’s visual politics (Cooke, 2025e).

These online spaces function as affective economies (Ahmed, 2014), wherein emotions are not privately held but publicly exchanged, shaping communal identity through likes, comments, and shares (Ahmed, 2014; Cooke, 2025e). Followers respond to Cassar’s narratives with grief, rage, reverence, and resolve, reinforcing the spiritual validity of the cause through digital reciprocity (Cooke, 2025e). Each interaction becomes a micro-ritual of belonging (Cooke, 2025e).

Social media also enables the formation of what Lorenzi (2020) terms “algorithmic kinship,” affective bonds forged through repeated digital engagement (Lorenzi, 2020; Cooke, 2025e). The architecture of the platforms ensures that emotionally provocative content gains greater visibility, creating feedback loops that intensify belief and belonging (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s community thus becomes bound not only by ideology but by the shared rhythm of ritualized online activity: livestreams, photo commentaries, story reposts, and call-and-response affirmations (Cooke, 2025e).

Cassar’s narrative architecture often mimics liturgical form (Cooke, 2025e). Posts begin with expressions of mourning or outrage, proceed through a retelling of sacred violation (such as a DLALC development), and conclude with invocations of resistance, awakening, or love (Cooke, 2025e).

This para-liturgy converts secular political conflict into spiritual ceremony (Cooke, 2025e). His followers are not just observers; they are initiated co-participants in the drama of settler redemption (Cooke, 2025e). This ritual form aligns closely with what Assaf (2011) and Brennan (2019) identify as “white shamanism,” in which settler spiritual practitioners appropriate Indigenous ritual forms to construct an imagined moral and cultural legitimacy (Cooke, 2025e).

This ritualization of online space is deeply political (Cooke, 2025e). CEA’s social media engagement produces a binary cosmology: the awakened guardians of sacred land versus the desecrating forces of institutional corruption (Cooke, 2025e). Aboriginal institutions like DLALC are rarely critiqued in nuanced terms. Instead, they are symbolically flattened, rendered as betrayers of Country or spiritually compromised authorities (Cooke, 2025e). This discursive violence is all the more potent for being cloaked in reverential language (Cooke, 2025e).

Moreover, social media offers a stage for the performance of charismatic authority (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s digital presence draws on techniques from wellness influencers, New Age spirituality, and activist branding (Cooke, 2025e). His role as “protector” is visually reinforced through imagery of rugged landscapes, ritual engagement, and moments of meditative stillness (Cooke, 2025e).

His charisma isn’t static; it’s maintained through continuous emotional labor and digital curation (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s online mobilization strategy also draws from QAnon-affiliated aesthetic and emotional logics (Cooke, 2025e). As Moskalenko et al. (2021) note, QAnon’s digital rituals rely on communal decoding, spiritualized resistance, and epistemic enclaves reinforced through algorithmic design (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s followers experience his online presence as a sacred feed, each post a moment of revelation, affirmation, or encoded truth (Cooke, 2025e).

Importantly, social media also shields CEA from scrutiny (Cooke, 2025e). Attempts at fact-checking or legal clarification are often reinterpreted within the group as attacks on their spiritual identity (Cooke, 2025e). This is consistent with the affective logic of conspirituality: truth is not established through reason but revealed through feeling (Cooke, 2025e). Cassar’s followers are emotionally immunized against contradiction, because alternative narratives are experienced not as differences of opinion but as threats to sacred belonging (Cooke, 2025e).

Epistemic Control and Behavioural Entrapment

Central to the operation of high-control groups is the monopolization of truth and reality (Richardson, 1993). Both the GuriNgai and CEA networks exhibit classic features of what Lifton (1989) identified as “milieu control,” a process through which a group limits access to external information while tightly regulating internal discourse (Lifton, 1989). Followers are fed curated information through closed online forums, livestream rituals, in-group storytelling, and mythopoetic teachings that reinforce the group’s cosmology (Richardson, 1993). These systems replace empirical verification with revealed truth (Lifton, 1989).

Within these frameworks, dissent is not interpreted as an invitation to dialogue, but as betrayal (Lalich, 2004). Members who question the fabricated genealogies or false Aboriginal claims made by GuriNgai leaders such as Tracey Howie or Neil Evers are cast as either “government agents,” “colonial sympathizers,” or “spiritually lost” (Cooke, 2025d). Similarly, within CEA, those questioning the scientific falsity of the Kariong Glyphs or opposing their slander against Darkinjung LALC are branded as morally bankrupt or complicit in environmental destruction (Cooke, 2025e).

The epistemic closure is reinforced through social and spiritual rituals, including ceremonies held at the Kariong site, bushwalks guided by Jake Cassar, and seasonal gatherings under the guise of ecological protection (Jake Cassar Bushcraft, n.d.).

These events double as indoctrination settings, embedding the group’s mythic narrative within an emotional and affective community experience (Richardson, 1993). As Hassan (2015) and Lalich (2004) describe, such rituals operate as powerful reinforcement mechanisms, particularly when combined with threats of spiritual harm or ancestral shame (Hassan, 2015; Lalich, 2004).

This isn’t merely a case of misinformation. It’s the deliberate replacement of pluralistic knowledge systems with dogma (Lifton, 1989). The groups maintain narrative purity by invoking sacred concepts, such as “Country,” “spirit,” and “law,” while refusing engagement with Aboriginal cultural authority, linguistic accuracy, or legal genealogy (Kwok, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024). In this sense, they construct what Richardson (1993) termed “bounded ideologies”—totalizing belief systems insulated from critical reflection (Lalich, 2004).

Moreover, the use of behavioral control mechanisms is apparent in how members are conditioned to perform settler-Indigenous roles (Cooke, 2025e). GuriNgai adherents adopt Aboriginal names, wear symbolic regalia, and speak in faux-Cultural idioms (Cooke, 2025d).

CEA activists are encouraged to become “guardians” of specific sites, to bear “truths” about suppressed histories, and to evangelize the gospel of Kariong’s glyphs (Cooke, 2025e). These performances create a simulacrum of identity and authority that mimics but displaces real Aboriginal law (Cooke, 2025d).

The result is a deeply embedded echo chamber. Members become psychologically invested in the mythology and group status, and simultaneously alienated from alternative sources of knowledge (Richardson, 1993). This creates a psychological double bind, what Singer (2003) referred to as the cultic milieu’s emotional trap, where exit becomes not only socially costly but spiritually devastating (Singer, 2003). Many fear spiritual exile, ancestral betrayal, or public shame if they disengage (Grant, 2022).

Such epistemic and behavioral entrapment further sustains the political function of these cults. Once enmeshed in these networks, members are not merely misinformed; they are ideologically armed against Aboriginal sovereignty (Cooke, 2025d).

They become grassroots vectors of disinformation, spreading myths, opposing Aboriginal-led developments, and rallying behind false claims of custodianship (Cooke, 2025e). As Montell (2021) and Anthony & Robbins (2004) note, this weaponization of belief is one of the most dangerous capacities of cults: their ability to transform narrative into action under the illusion of sacred purpose (Zablocki, 2001).

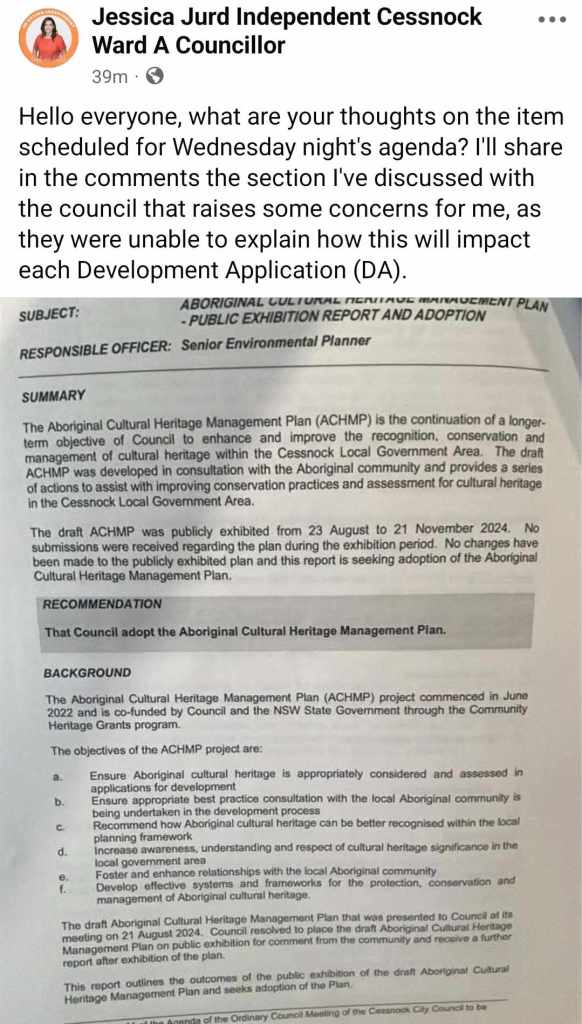

4. Cultural, Legal, and Historical Legitimacy: Darkinjung LALC versus the GuriNgai Group

A comprehensive comparison of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) and the non-Aboriginal GuriNgai group reveals fundamental differences in cultural legitimacy, legal authority, and historical continuity (Cooke, 2025g).

DLALC is a legislatively constituted body under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), which not only affirms its Aboriginal identity but also confers statutory powers to acquire, manage, and develop land for the benefit of its members (Cooke, 2025g). This legal recognition grants DLALC authority in land use decisions, enabling it to undertake planning proposals such as the Kariong development with official endorsement, access to statutory planning frameworks, and direct accountability to state and community governance mechanisms (Cooke, 2025g).