Jake Cassar is a Central Coast ‘bushcraft’ tourism operator, conspiracy promoter, and founder of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), a group opposing several development projects on land owned by the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC).

Cassar has campaigned against proposed developments exclusively undertaken by Aboriginal people and organisations, framing himself as a defender of “sacred lands” and sensitive ecosystems (Bovill, 2020). In media interviews he has publicly acknowledged Darkinjung’s legal rights but argued for alternative uses (e.g., a cultural heritage centre) instead of housing. (Lapham, 2020). However, his wider activities—including yowie hunting, pseudoarchaeology, eco-spiritual performances, and promotion of Big Cat sightings—cast doubt on his credibility as an environmentalist and raise deeper questions about the legitimacy of his campaign (Cooke, 2025a; Richmond-Manno, 2021).

This report examines the political, ecological, and cultural narratives Cassar and CEA employ in these campaigns, situating them within broader frameworks of settler environmentalism, ecofascism, and conspiratorial rhetoric. It draws on academic literature on conspiracy belief, Indigenous sovereignty, settler colonialism, and affective propaganda, as well as media coverage and Cassar’s own social media posts. It also reviews Indigenous responses and considers how this case reflects wider “settler-conspiracist” strategies in Australia.

Narratives of the Coast Environmental Alliance

CEA’s public messaging intertwines environmental conservation, Aboriginal spirituality, and distrust of authorities. Three core strands emerge:

Ecological Conservation: CEA frames the contested sites as ecologically fragile and nationally significant. For example, CEA spokespersons warn that the Kariong wetlands are “endangered” and essential to local fisheries, accusing DLALC of planning a “devastating, far-reaching and permanent” development (Coast Community News, 2025b). CEA has formally complained that official planning documents on the NSW government website are “dishonest, deliberately misleading” and underplay environmental risks (Coast Community News, 2025c).

Cultural/Spiritual Guardianship: CEA emphasizes a non-Aboriginal ‘custodianship’, sacredness and Dreaming to justify its stance. Cassar and allies repeatedly invoke “ancient sites” and claim custodianship over Country. In one CEA-aligned press release, it is asserted that “the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council has no moral right to desecrate land that predates all claims of ownership… It is not theirs to sell” (Cassar, 2020). Cassar’s rhetoric often describes the land as a global “sacred site” whose ancient knowledge would be “lost for all humanity” if developed (Strong, 2020).

Political/Misinformation Conspiracy: CEA’s messaging frequently alleges corruption or secret collusion between government and developers. For instance, CEA lauded the potential of a NSW Ombudsman’s inquiry in response to CEA accusing the Planning Department of aiding Darkinjung by publishing “misinformation” on a public website (Coast Community News, 2025c). They argue that government websites deliberately minimise risks and “support the developer,” echoing a conspiracist distrust of state institutions.

Together, these narratives position Cassar and CEA as heroic protectors of nature and culture, but they rely on polarizing tropes: praising Aboriginal heritage in abstract terms while simultaneously portraying an Aboriginal-led land council as a dangerous, dishonest “other” (Cooke, 2025b).

Conspirituality, Yowies, and Fringe Beliefs

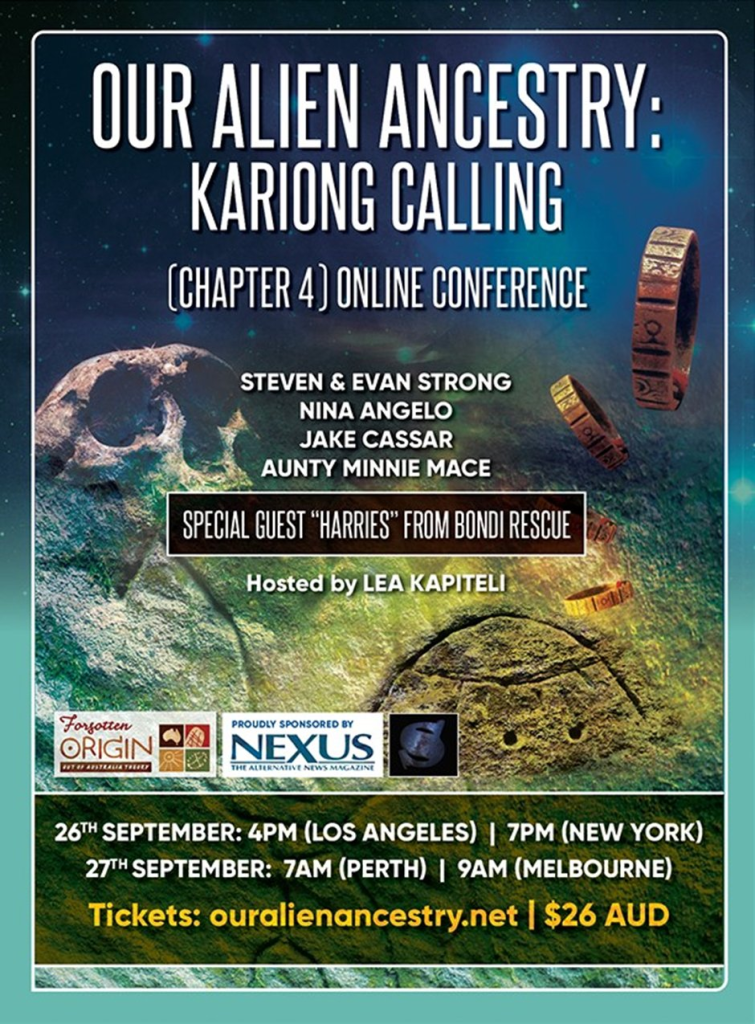

Cassar’s activism must be understood in the context of his long-standing engagement with fringe spiritual and paranormal discourses. He has appeared on yowie-themed radio programs (Richmond-Manno, 2021), spoken at conferences about Big Cat sightings, and publicly endorsed the Gosford Glyphs as legitimate ancient relics (Cassar, 2020). His personal Facebook videos and online content regularly mix quasi-spiritual messages with unsupported historical and archaeological claims. Cassar describes himself as a protector of “ancient wisdom” and has posted content promoting yoga, consciousness awakening, and “cosmic” Dreamtime cosmologies that bear little relation to authentic Aboriginal belief systems (Ayurveda World, n.d.).

This conspiratorial-spiritual fusion is emblematic of what Halafoff et al. (2022) term conspirituality: the merger of conspiracy theories and spiritual beliefs. It features a simultaneous rejection of institutional knowledge and reverence for mystical insight. Cassar’s engagement with yowie sightings, glyphs, and “sacred landscapes” plays into this affective space, evoking an urgent apocalyptic register to justify resistance to development.

In a telling example, Cassar responded to a colleague’s work by distancing his campaign from mainstream climate action: “Some may argue that we could get the typical climate change activists offside, but they don’t really support us anyway. And no matter how hard we try. I’m going to read this again. Finally something outside of the box that actually makes sense” (Cassar, 2025).

This comment reflects a broader tendency to dismiss scientific consensus and professional environmental advocacy in favour of contrarian, populist, or conspiratorial framings. Cassar’s rejection of “typical” activists mirrors a larger movement of anti-institutional climate scepticism, where settler environmentalists bypass scientific frameworks in favour of spiritualised or anecdotal “knowledge.”

Settler Environmentalism and Ecofascist Frameworks

Scholars have shown how environmental arguments can mask settler-colonial agendas. Settler environmentalism refers to ways in which non-Indigenous settlers claim to defend “nature” while ignoring Indigenous sovereignty (Moreton-Robinson, 2015). In this case, Cassar’s narratives exemplify this dynamic: he and allied groups repeatedly cast themselves as the true custodians of Country and Aboriginal heritage, even though DLALC holds statutory cultural authority (Cooke, 2025b).

Cassar’s campaigns thus use environmentalist language to oppose projects led by the Aboriginal land council. Academics note that this is a form of settler nativism: settlers rhetorically “nativize” themselves by invoking Indigenous identity and “caring for Country,” thereby eliding the settler-colonial origins of their claims (Moreton-Robinson, 2015).

The rhetoric also bears traits of ecofascism, where environmental concern is merged with exclusionary ideology. Although Cassar does not explicitly espouse white supremacist beliefs, his framing echoes core ecofascist themes: the notion that environmental degradation is a catastrophic threat and that preserving “nature” is paramount, potentially at the expense of human rights (Walsh, 2022). Cassar’s narrative suggests that Darkinjung (an Indigenous authority) is itself an “outsider” threat to the land.

Cultural Appropriation and Racist Caricatures

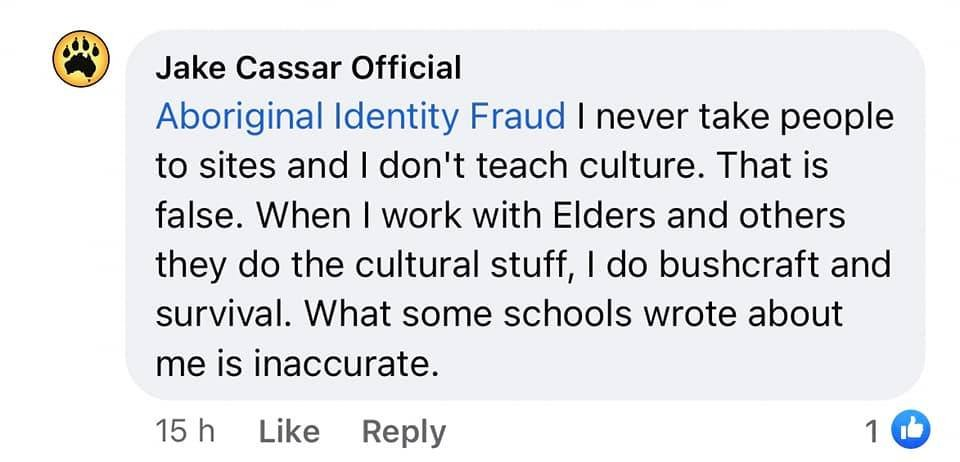

Cassar’s engagement with Aboriginal cultural motifs is not limited to rhetorical appropriation—it extends into performative mimicry and parody. In various public videos and workshops, he has presented himself using Aboriginal-style face paint, tools, and terms. He has posted images and videos online in which he plays the didgeridoo, stages pseudo-Initiation scenes, or references the “old ways” with vague mysticism, despite not being Aboriginal.

One video features Cassar describing his bushcraft work as a continuation of the “ancient wisdom of the ancestors,” using Aboriginal-sounding intonations to describe fire-making or spearfishing techniques (Cassar, 2022).

These acts construct an offensive caricature of Indigenous knowledge, rebranded through a white spiritualist lens. Cassar’s performances reinforce what Moreton-Robinson (2015) calls “the white possessive”—a mode of entitlement to Indigenous culture that ignores Indigenous sovereignty.

Moreover, Cassar has used these appropriated cultural symbols to undermine Aboriginal organisations. In a Facebook post, he referred to DLALC’s Kariong proposal as a “cultural crime” and suggested that the land should be protected by those with “a true connection to the spirit of Country” (Cassar, 2021).

Such statements imply that Aboriginal people exercising legal rights to develop their land are less spiritually or culturally connected than he is—a textbook expression of settler-colonial inversion. By assuming and distorting Indigenous forms of knowledge, Cassar enacts a racialised mockery disguised as reverence.

Creation of Conspiracies about Aboriginal Land Rights

Among Cassar’s most damaging interventions is the promotion of the conspiratorial idea that “no Crown land is safe” from Aboriginal land claims. This trope, repeatedly invoked on CEA and Cassar’s social media platforms, frames Aboriginal people and organisations as an existential threat to public space. It evokes fear that all government-owned land might be reclaimed for private Aboriginal purposes. Cassar and his supporters use this rhetoric to galvanise opposition by portraying Aboriginal sovereignty not as justice or redress, but as a form of greedy incursion (Cassar, 2023). This narrative fuels racist anxieties about land loss and feeds broader far-right talking points about Indigenous overreach and preferential treatment. Rather than engaging in good-faith dialogue about reconciliation or co-management, this framing presents Aboriginal land rights as an elite conspiracy working against ordinary Australians.

Indigenous Sovereignty and Settler Colonial Context

CEA’s opposition to DLALC projects sits uncomfortably with concepts of Indigenous sovereignty. The Darkinjung LALC is a legally recognized Aboriginal organization whose land-use decisions are an exercise of Aboriginal self-determination (Moreton-Robinson, 2015). Citing Darkinjung’s “right to self-determination” for economic development may appear superficially supportive, but Cassar and his allies have concurrently undermined Darkinjung’s cultural authority (Cooke, 2025b).

Indigenous leaders have pushed back. DLALC spokespersons have stated that projects like Kariong are intended for community benefit, including affordable Aboriginal housing and cultural preservation (Lapham & Vince, 2020). The local Aboriginal community have also criticized Cassar’s movement, and have published analyses accusing Cassar’s allies of “manufacturing Aboriginal identity” and performing a “racialised gatekeeping function” (Cooke, 2025b).

Media and Social Media Coverage

Local media coverage has played a central role in amplifying CEA’s perspective. Coast Community News (CCN), a prominent regional outlet, has published dozens of articles on the DLALC projects, overwhelmingly quoting Cassar and other allied figures while giving scant attention to DLALC’s case (Coast Community News, 2025b). Academic commentators note that CCN often labels DLALC as “developers” or “controversial,” whereas Cassar et al. are cast as saviors of the environment (Cooke, 2025b).

Social media has similarly mirrored this one-sided framing. CEA and affiliated Facebook groups circulate posts alleging imminent destruction of “sacred groves” by Darkinjung. Cassar himself has praised acts of defiance; in 2023 he reportedly celebrated an extension of the rezoning deadline as a “win” after mass submissions (Coast Community News, 2025b). Videos posted to Facebook and YouTube from Cassar’s circle regularly feature mystical invocations, Bigfoot-like yowie stories, and allegations of political conspiracies obscuring ancient ‘Aboriginal’ truths, known only to non-Aboriginal People.

Conclusion

Jake Cassar’s Coast Environmental Alliance’s campaign illustrates a broader pattern: small networks of conspiracist-tinged activists in Australia repeatedly useing environmental and cultural rhetoric to contest Indigenous land projects. Academically, these are framed as settler-conspiritualist strategies—the merger of settler colonial impulses with spiritualized conspiracy thinking (Halafoff et al., 2022). The CEA case thus exemplifies how disaffection with modern society (climate anxiety, distrust in institutions) can be channeled into racialized populism. Cassar’s embrace of yowie myths, pseudoarchaeology, cultural appropriation, and eco-spiritual conspiracies exposes the opportunistic and racially offensive dimensions of this activism, which ultimately undermine rather than protect Aboriginal sovereignty.

JD Cooke

References

Ayurveda World. (n.d.). Jake Cassar. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://www.ayurvedaworld.org/jake-cassar

Cassar, J. (2020, September 12). Darkinjung Land Council development opposed [Press release]. Forgotten Origin. https://forgottenorigin.com/please-help-save-kariong

Cassar, J. (2021, March 12). Facebook post. https://www.facebook.com/jakecassarbushcraft/posts/610373919568151/

Cassar, J. (2022, April 19). Bushcraft post [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/jakecassarbushcraft/posts/864642632379702

Cassar, J. (2023, October 5). Facebook post. https://www.facebook.com/groups/coastenvironmentalalliance/posts/10161012253343427/

Coast Community News. (2025b, November 16). Kariong development back in the spotlight. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2023/11/kariong-development-back-in-the-spotlight

Coast Community News. (2025c, March 25). Call for halt on planning process for Kariong development. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2024/03/call-for-halt-on-planning-process-for-kariong-development

Cooke, J. D. (2025a). The false mirror: Settler environmentalism, identity fraud, and the undermining of Aboriginal sovereignty on the Central Coast of NSW. https://guringai.org/2025/06/06/the-false-mirror-settler-environmentalism-identity-fraud-and-the-undermining-of-aboriginal-sovereignty-on-the-central-coast

Cooke, J. D. (2025b). Save Kincumber Wetlands, Coast Environmental Alliance, and the denial of Aboriginal sovereignty—A long, gone on too long. https://guringai.org/2025/06/14/save-kincumber-wetlands-coast-environmental-alliance-and-the-denial-of-aboriginal-sovereignty

Halafoff, A., Singleton, A., Bouma, G., & Rasmussen, M. L. (2022). Freedoms, faiths and futures: Teenage Australians on religion, sexuality and diversity. Bloomsbury Academic.

Lapham, J., & Vince, M.-L. (2020, July 9). Battlelines drawn over Kariong housing project proposed by Darkinjung Aboriginal Land Council. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-09/darkinjung-kariong-housing-development-tensions-mount/12426348

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Richards, I., Jones, C., & Brinn, G. (2022). Eco-fascism online: Conceptualizing far-right actors’ response to climate change on Stormfront. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2022.2156036researchgate.net+1en.wikipedia.org+1

Richmond-Manno, S. (2021, December 6). Saving Sacred Land from Corruption with Jake Cassar (EP #83) [Podcast transcript]. Superfeast. https://www.superfeast.com.au/blogs/articles/saving-sacred-land-from-corruption-with-jake-cassar-ep-83

Strong, E. (2020, September 12). Please Help Save Kariong. Forgotten Origin. https://forgottenorigin.com/please-help-save-kariong

Walsh, C. (2022). Ecofascism: A theoretical introduction. Environmental Humanities, 14(1), 1–20.

Leave a reply to False Custodians, Real Homelessness: Bellamy, Cassar and CEA’s Role in the Central Coast Housing Crisis – Bungaree.org Cancel reply