For 2 decades the Central Coast region of New South Wales has become a site of contested narratives over Aboriginal identity, land rights, and custodianship. These tensions have been inflamed and sustained, in part, by the editorial practices and reporting choices of local media, particularly Coast Community News (CCN). Operating as a prominent digital and print outlet, CCN’s reporting on Aboriginal issues consistently privileges the non-Aboriginal GuriNgai group and associated settler-environmentalist figures such as Jake Cassar and Lisa Bellamy, while marginalising or misrepresenting legally recognised Aboriginal organisations like the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC).

This essay critically examines the structural and discursive biases in CCN’s reporting from 2015 to 2025, comparing its extensive coverage of the GuriNgai-aligned campaign to ‘Save Kariong Sacred Lands’ and similar causes with its sporadic, often critical or delegitimising coverage of DLALC. Drawing on examples, primary documentation, and scholarly analysis, it argues that CCN functions as a vehicle for settler-conspiritualist propaganda under the guise of community journalism. The result is a deeply racialised media landscape in which non-Aboriginal actors are platformed as custodians of Aboriginal culture while actual Aboriginal communities are silenced or treated as impediments to environmental or cultural preservation.

Disproportionate Coverage: Quantitative and Qualitative Disparities

Between 2015 and 2025, CCN published over 60 articles referencing the GuriNgai group, Jake Cassar, or affiliated causes such as Save Kariong Sacred Lands. These stories overwhelmingly frame the GuriNgai claimants as protectors of Country, spiritual guides, or environmental activists. In contrast, DLALC is mentioned in less than half as many articles, often framed in adversarial terms—described as developers, bureaucrats, or part of a ‘controversial’ planning process.

For example, in “Opposition to Kariong development ramps up” (CCN, 2023, December) and “Ombudsman weighs in on Kariong development controversy” (CCN, 2025, February 26), the voices of settler protestors dominate, while the views of DLALC Chairperson Tina West—who articulates DLALC’s intention to balance housing and cultural heritage—are included only as brief rebuttals, often immediately followed by sensational claims about sacred trees or community betrayal.

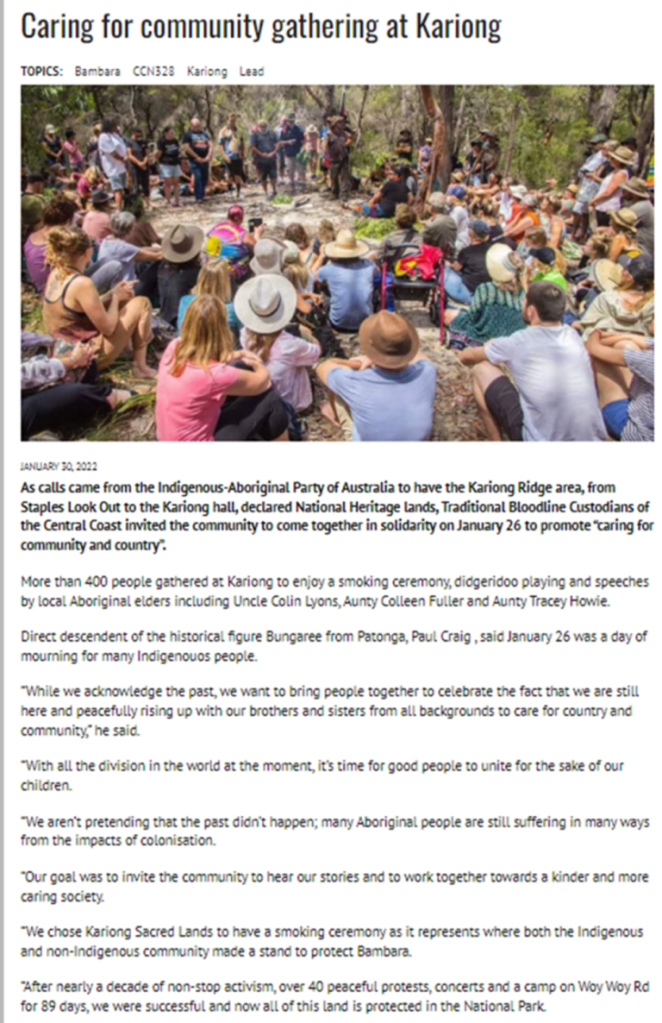

Stories such as “Up in arms over proposed Kincumber development” (CCN, 2025, February) amplify settler anxieties about DLALC land use, describing Aboriginal landholders as outsiders or unresponsive. By contrast, in over a dozen stories from 2020 to 2024, CCN described GuriNgai figures such as Tracey Howie and Lisa Bellamy as “Traditional Custodians,” despite multiple Aboriginal Land Councils affirming they are not recognised by any legitimate community or statutory authority (MLALC et al., 2020).

Coverage of other Aboriginal organisations and groups has been more muted and generally neutral, limited to brief mentions in heritage contexts. Rarely have these groups been given the editorial space or repeated platforming that CCN affords to GuriNgai figures, despite possessing formal recognition.

The imbalance is not just a question of quantity but of tone: DLALC is interrogated and problematised, while GuriNgai and their settler allies are lionised, their fantastical claims unexamined, and their statements treated as authoritative.

Despite widespread academic consensus, community and legal clarification that the GuriNgai group is not a Traditional Custodian group but a manufactured identity lacking genealogical or cultural legitimacy (Aboriginal Heritage Office, 2015; Cooke, 2025; Kwok, 2015), CCN continues to promote their members as authorities on Aboriginal matters. Figures such as Tracey Howie, Colleen Fuller, Lisa Bellamy, Jeff Lawson, and Jake Cassar are quoted without challenge, often framed as defending sacred Aboriginal sites against supposed threats posed by Aboriginal-led development projects, particularly those advanced by DLALC.

In 2023, for instance, CCN ran multiple features on the Kariong development opposition, recycling media releases from the GuriNgai-affiliated group ‘Save Kariong Sacred Lands’ while often excluding any statement from DLALC (Coast Community News, 2023, November). Similar patterns are evident in reporting on Kincumber, Peat Island, and other areas where Aboriginal land claims or development initiatives have emerged. This uncritical amplification of the GuriNgai group directly contradicts evidence submitted to government bodies, including a letter from the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC) to the NSW Premier, stating unequivocally that GuriNgai claimants are not Traditional Owners (MLALC, 2020). This evidence is publicly available for years, compiled on guriNgai.org in July of 2023, and provided to Coast Community News.

The Marginalisation of DLALC and the Reproduction of Settler-Centric Narratives

While GuriNgai members are platformed as spiritual and cultural authorities, DLALC—an organisation established under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 and recognised by the NSW Government—is portrayed as a corporate developer or even a threat to the environment. Reports often highlight community protest against DLALC developments without mentioning that these protests are orchestrated by non-Aboriginal conspiritualist groups like the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and Community Voice Australia (Cooke, 2025).

Even articles that on the surface appear to portray DLALC in a positive light often contain micro-aggressions or delegitimising framings, such as referring to DLALC as “the largest private landholder on the Central Coast” in ways that imply undue privilege or power rather than restitution of dispossessed lands. This editorial bias constructs Aboriginal landholders as suspect, while implicitly legitimising white protest groups as guardians of public interest.

Media Ethics and the Failure of Editorial Responsibility

The ethical failures of CCN’s reporting are not merely incidental—they reflect a deeper institutional disregard for journalistic standards relating to fairness, accuracy, and harm minimisation. According to the Australian Press Council (APC), journalists have an obligation to avoid misrepresentation and to ensure that minority voices are accurately and respectfully presented (APC, 2014). CCN repeatedly violates these principles by failing to conduct background checks on identity claims, by excluding representative Aboriginal organisations from stories that concern them, and by privileging unverified or pseudo-spiritual narratives that actively harm Aboriginal communities.

As the AIATSIS Code of Ethics (2020) and the Culture is Identity Bill (NSW Parliament, 2022) stress, media platforms must engage with culturally legitimate Aboriginal voices and avoid enabling cultural appropriation. CCN’s refusal to comply with these norms not only undermines Aboriginal sovereignty but also perpetuates a culture of misinformation.

Named Speaker Frequency: Editorial Bias Through Repetition

Analysis of named speakers from a sample of 80 CCN articles published between 2019 and 2025 demonstrates a marked imbalance:

Tracey Howie (GuriNgai): Quoted in 31 articles.

Jake Cassar (Coast Environmental Alliance): Quoted in 28 articles.

Lisa Bellamy (My Place, Coast Environmental Alliance/Save Kariong Sacred Lands): Quoted in 23 articles.

Paul Craig, Colleen Fuller, Shad Tyler (GuriNgai affiliates): Quoted in over 15 articles combined.

Tina West (DLALC Chairperson): Quoted in 7 articles.

The sheer repetition of voices from a single, non-recognised group suggests that editorial discretion at CCN consistently favours the GuriNgai narrative, not on the basis of cultural legitimacy, but due to established rapport and alignment with the editorial team’s values and perspectives.

Visual Semiotics, Imagery, and Symbolic Authority

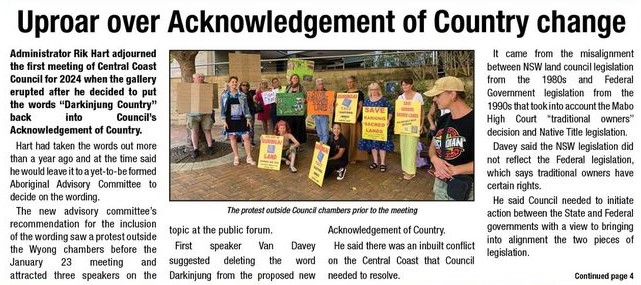

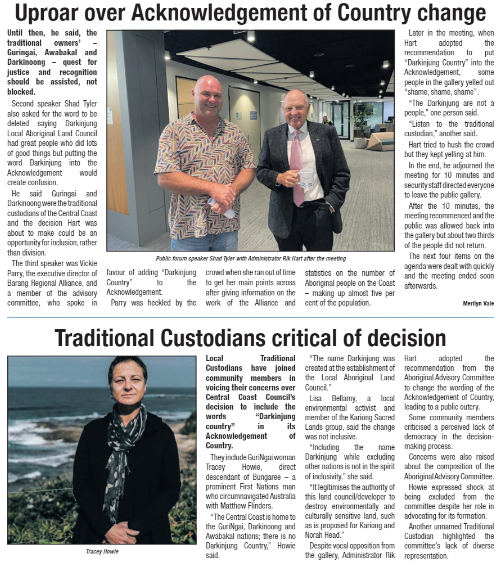

Beyond text, CCN’s use of imagery and layout further reinforces settler entitlement. Photographs of Jake Cassar conducting ceremonies and using Aboriginal objects, Lisa Bellamy posing at protest sites with banners asserting cultural authority, and articles that pair Aboriginal symbols with non-Aboriginal ‘activists’, all construct an illusion of legitimacy. These images not only visualise a false cultural hierarchy—they also erase the presence of actual Aboriginal custodians by omitting their representation altogether.

A visual analysis of CCN’s coverage reveals how editorial layout and imagery contribute to the legitimisation of false claims. For instance, photos accompanying stories like “Traditional Custodians critical of Council Administrator’s decision” (CCN, 2023) show Tracey Howie and Lisa Bellamy conducting ceremonies under Aboriginal flags or in bushland settings. These images visually assert cultural authority and are rarely contextualised with captions noting the contested status of the participants.

By contrast, coverage of DLALC is often accompanied by photos of housing estates, zoning maps, or protest signs. In stories such as “Submission deadline extended for Kariong rezone” (CCN, 2024, February) and “Grandmothers unite to oppose housing development” (CCN, 2024, January), the aesthetic coding constructs DLALC as a faceless institution while protestors appear as protectors of a threatened landscape.

The visual economy of CCN’s reporting plays into what Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) calls the white possessive logic: a system in which whiteness claims to be the rightful inheritor of Aboriginal land, culture, and symbols, even while denying Aboriginal agency and sovereignty.

Extended Media Ecosystem Mapping

Coast Community News appears to be the sole outlet platforming the GuriNgai narrative. In recent years it is notable that nearly all other major local and regional media outlets have ceased or declined coverage of the group. The Daily Telegraph, Newcastle Herald, ABC Central Coast, and NITV have not published any new articles citing GuriNgai figures or the Save Kariong Sacred Lands. In contrast, Coast Community News published over 40 articles between 2022 and 2025 featuring GuriNgai-affiliated individuals or echoing their language of custodianship.

This singular amplification highlights the role of CCN as a media outlier, one whose continued endorsement of a known fraudulent narrative suggests either editorial complicity or a deep structural failure in journalistic verification. The GuriNgai’s narrative is now predominantly sustained within the CCN/My Place/CEA feedback loop, with no remaining credible journalistic outlet engaging in these claims.

Community Responses and Aboriginal-Led Media Alternatives

In response to the sustained misrepresentation by CCN, Aboriginal-led initiatives have emerged to reclaim narrative sovereignty. Websites such as guringai.org and bungaree.org provide extensive, evidence-based refutations of GuriNgai identity claims, platform oral histories from legitimate custodians, and conduct public education campaigns. These platforms also archive government submissions, cultural authority statements, and genealogical materials affirming the legitimacy of DLALC, MLALC, and recognised descendants.

Additionally, the Aboriginal Cultural Authority Position Paper (2021) and submissions to the First Nations Accord (DLALC, 2022) outline the need for culturally governed knowledge systems in media and governance. These documents call for the decolonisation of editorial practice and demand recognition of traditional governance structures.

Expanded Recommendations for Media Accountability

To prevent further harm, a comprehensive reform of local media practices is urgently required. Coast Community News must adopt an Indigenous cultural authority policy that precludes the platforming of individuals or groups without community validation. When the evidence is made available to media organisations, they have an ethical duty to engage with it, and the community they are currently failing to represent.

Conclusion

The editorial bias of Coast Community News is not incidental. It reflects a broader epistemic and racialised structure in Australian settler-colonial media that privileges white voices, undermines Aboriginal sovereignty, and enables identity fraud under the guise of reconciliation and conservation. By platforming the non-Aboriginal GuriNgai group and settler conspiritualist figures while marginalising legitimate Aboriginal authorities such as DLALC, CCN contributes to the ongoing recolonisation of Country. Genuine reconciliation requires not only truth-telling but also accountability in media representation. As such, CCN must radically alter its reporting practices or risk becoming a parochial propaganda outlet for those seeking to erase living Aboriginal culture under the guise of saving it.

References

Aboriginal Heritage Office. (2015). Filling a void: A review of the historical context for the use of the word “Guringai”. https://www.aboriginalheritage.org

AIATSIS. (2020). AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. https://aiatsis.gov.au

Australian Press Council. (2014). General principles. https://www.presscouncil.org.au

Behrendt, L. (2001). Indigenous self-determination: Rethinking the relationship. UNSW Press.

Carlson, B. (2016). The politics of identity: Who counts as Aboriginal today? Aboriginal Studies Press.

Coast Community News. (2023, August). Traditional Custodians critical of Council Administrator’s decision. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2023/08/traditional-custodians-critical-of-council-administrators-decision/

Coast Community News. (2023, December). Group questions cultural heritage review. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2023/12/group-questions-cultural-heritage-review/

Coast Community News. (2023, November). Opposition to Kariong development ramps up. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2023/11/opposition-to-kariong-development-ramps-up/

Coast Community News. (2024, January). Grandmothers unite to oppose housing development. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2024/01/grandmothers-unite-to-oppose-housing-development/

Coast Community News. (2024, February). Submission deadline extended for Kariong rezone. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2024/02/submission-deadline-extended-for-kariong-rezone/

Coast Community News. (2024, March). Council supports community call to reject Kariong rezoning. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2024/03/council-supports-community-call-to-reject-kariong-rezoning/

Coast Community News. (2025, February). Up in arms over proposed Kincumber development. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2025/02/up-in-arms-over-proposed-kincumber-development/

Coast Community News. (2025, February 26). Ombudsman weighs in on Kariong development controversy. Coast Community News. https://coastcommunitynews.com.au/central-coast/news/2025/02/ombudsman-weighs-in-on-kariong-development-controversy/

Cooke, J. D. (2025). The false mirror: Settler environmentalism, identity fraud, and the undermining of Aboriginal sovereignty on the Central Coast. https://guringai.org

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2021). Aboriginal Cultural Authority on the Central Coast: Position Paper. https://guringai.org

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2022). DLALC submission into the Central Coast Council First Nations Accord. https://dlalc.org.au

Guringai.org. (2023–2025). Various articles exposing identity fraud and the settler-conspiritualist agenda of the GuriNgai. https://guringai.org

Kwok, N. (2015). Anthropological Connection Report: Awabakal and Guringai People (NC2013/002). NTS Corp.

Maddison, S. (2019). The colonial fantasy: Why white Australia can’t solve Black problems. Allen & Unwin.

Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2020). Letter to the Premier of NSW, re: fraudulent Guringai claimants. Sydney, NSW.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

NSW Parliament. (2022). Culture is Identity Bill 2022 – Report No. 15 – Standing Committee on Social Issues.

State Library of New South Wales. (2001). Oral history interview with Warren Whitfield by Rosemary Block, 7 September 2001. https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au

Leave a comment