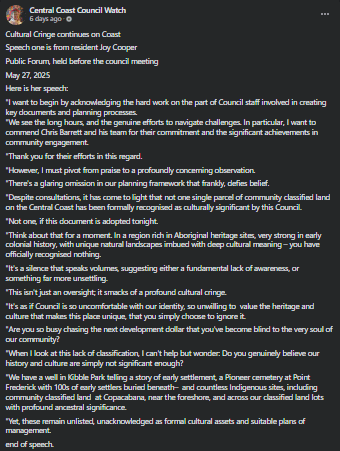

As an Aboriginal man of the Carigal – Marramarra of the Hawkesbury River and Broken Bay, I must respond to the recent remarks by Mrs Joy Cooper at the Central Coast Council meeting with clarity and truth. While her public expression of concern over the lack of cultural heritage classification in Council’s land planning instruments is noted, her intervention is both misinformed and misdirected. It is not only out of step with the legitimate structures of Aboriginal self-determination but risks further undermining the authority of those with rightful cultural standing.

Cooper’s claim that Central Coast Council has “officially recognised nothing” in relation to Aboriginal cultural heritage ignores a complex legal and historical context in which the role of determining cultural significance is not, and has never been, the sole prerogative of local government. Under New South Wales law, the identification, classification, and protection of Aboriginal cultural heritage are legislative functions of State and Federal governments, not of local councils (NSW Aboriginal Land Council [NSWALC], 2011; NSW Council for Civil Liberties [NSWCCL], 2022). In fact, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) and the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) govern the management of Aboriginal cultural heritage, with Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) and the Office of Environment and Heritage holding the relevant authorities.

Critically, the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) is the only recognised cultural authority under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act for most of the Central Coast region, including Kariong and Copacabana. This has been affirmed in official submissions by DLALC and supported by the NSWALC and NTSCORP. In 2022, DLALC expressed grave concerns about individuals and groups attempting to insert themselves into cultural discussions without evidence of ancestry, land rights, or cultural authority, particularly those self-identifying under the historically fabricated term “Guringai” (DLALC, 2022; see also Aboriginal Heritage Office, 2015; Filling a Void Report).

Rather than engaging with these legitimate Aboriginal governance bodies, Joy Cooper has instead constructed a settler-centric narrative, one that centres her own indignation while failing to acknowledge the ongoing efforts of Aboriginal communities themselves. It is particularly telling that Cooper made no reference to consulting DLALC, the Metropolitan LALC, or any registered Traditional Owners in her address, even as she sought to speak to the “soul of our community.” This reflects a deeper pattern of what Indigenous scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) terms the “white possessive,” wherein non-Indigenous individuals claim to defend Aboriginal culture while ignoring Aboriginal sovereignty and decision-making.

Indeed, the sites Cooper referenced—such as Copacabana and Kibble Park—are already subject to Aboriginal knowledge systems, oral histories, and cultural governance, but those processes are deliberately excluded from colonial recognition frameworks. The failure to recognise Aboriginal cultural sites is not the fault of Council workers, but the result of outdated and racist legal regimes that continue to treat Aboriginal heritage as flora and fauna, governed by State wildlife legislation rather than Aboriginal law (NSWALC & NTSCORP, 2011; NSWCCL, 2022). This is precisely why there have been repeated calls for a standalone Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act that recognises the right of Aboriginal peoples to decide what is culturally significant and to manage their cultural heritage in accordance with their own traditions and laws (NSWALC, 2022; United Nations, 2007).

The solution to this injustice is not for non-Indigenous individuals like Cooper to present themselves as cultural champions. The solution lies in genuine engagement with and deference to the structures that Aboriginal people have fought for: Aboriginal Land Councils, Native Title bodies, and community-based Elders with cultural legitimacy and historical continuity. These are not symbolic institutions; they are legislated, democratically governed, and recognised under both domestic and international law (NSWALC, 2016; UNDRIP, 2007).

Mrs Cooper’s lack of engagement with Aboriginal people, organisations, or community-controlled governance structures suggests a troubling pattern of speaking about us rather than with us. Cultural authority does not derive from concern—it derives from Country, from kinship, from the continuous and unbroken transmission of law, story, and responsibility. As the Filling a Void report makes clear, the misuse and misapplication of fabricated identities like “Guringai” has created confusion and harm, particularly when such claims are made by individuals or groups with no genealogical, cultural, or historical links to the lands in question (Aboriginal Heritage Office, 2015).

In the end, Mrs Cooper’s impassioned performance may attract media soundbites and settler applause, but it offers nothing to Aboriginal sovereignty, nor does it reflect the will of the legitimate custodians of this Country. If she is serious about addressing the silence she describes, the path forward is clear: step back, listen, and support Aboriginal-led processes—not white commentary masked as advocacy.

References

Aboriginal Heritage Office. (2015). Filling a Void: A Review of the ‘Guringai’ Aboriginal Claim. Retrieved from https://guringai.org/documents

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2022). Submission to the NSW Parliamentary Inquiry into the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage (Culture is Identity) Bill.

New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). (2011). Our Culture in Our Hands: Submission with NTSCORP on Cultural Heritage Reform in NSW.

New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). (2016). NSWALC Submission to UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues: Conflict, Peace and Resolution.

New South Wales Council for Civil Liberties (NSWCCL). (2022). Submission to the Inquiry into the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage (Culture is Identity) Bill 2022.

United Nations. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Leave a comment